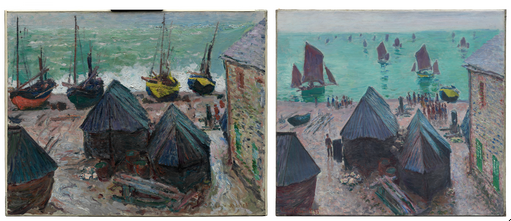

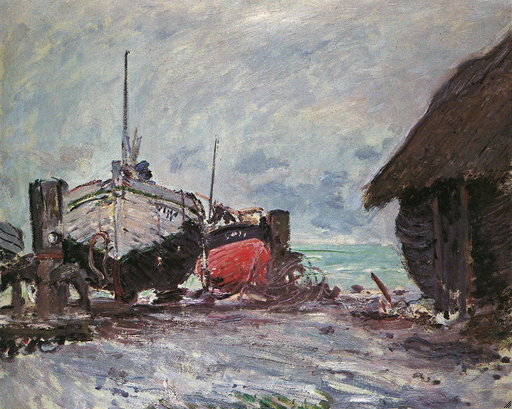

Cat. 22

Boats on the Beach at Étretat

1885

Oil on canvas; 65.5 × 81.3 cm (25 3/4 × 32 in.)

Signed: Claude Monet (lower right, in red-brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection, 1947.95

Cat. 23

The Departure of the Boats, Étretat

1885

Oil on canvas; 73.5 × 93 cm (28 15/16 × 36 19/16 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 85 (lower left corner, name in orange-red paint, year in reddish-brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Potter Palmer Collection, 1922.428

Room with a View: Hôtel Blanquet

Claude Monet first painted Étretat, a tourist site with a local fishing fleet, during the winter of 1868–69. He undertook a major painting campaign there in 1883; he returned in 1885 and again in February 1886 for a final, abbreviated trip. Located fifteen miles up the coast from Le Havre, Étretat was both accessible and challenging for the artist, offering at once spectacular views but also dangerously steep cliffs of flinty rock chiseled by crashing waves. Monet returned from his autumn 1885 campaign with fifty-one canvases, the majority of which featured the Falaise d’Amont (see cat. 21), the Falaise d’Aval, and the Aiguille (lit. “needle,” a pointed rock formation)—dramatic subjects that had appealed to earlier artists including Eugène Isabey and Gustave Courbet. Following the procedure he had developed to research sites chosen for their remoteness as well as for their artistic potential, Monet consulted popular guidebooks to locate the most picturesque views. At the same time, he ignored any sign of the tourist culture for which the descriptions were written, scheduling his trips to begin when the vacationers had departed and the beach reclaimed by local fishermen.

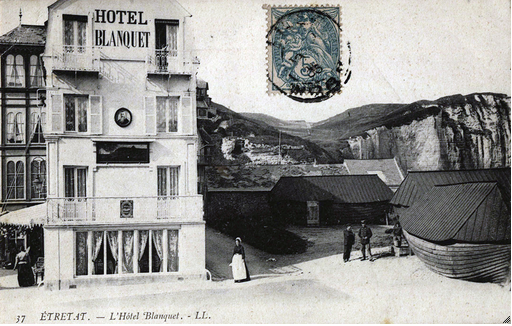

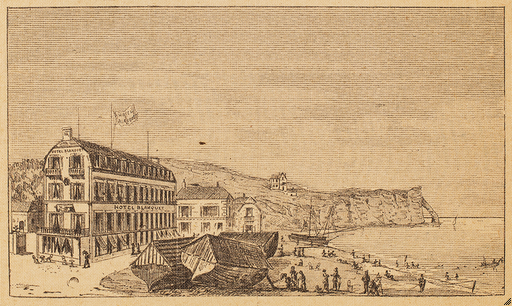

The inclement weather of the off-season sometimes kept Monet indoors, but he was still able to find workable motifs. As he mentioned in a letter to his companion, Alice Hoschedé, “In the afternoon, I worked in my room on my caloges seen in the rain, then I attempted to do, always through the window, a picture of the boats departing. . . . I want to complete a number of canvases, and I want to return.” The paintings he worked on during the 1885 trip include the Art Institute’s Boats on the Beach at Étretat and The Departure of the Boats, Étretat. They both show the view looking down from the top floor of the Hôtel Blanquet, where he stayed from mid-October through mid-December 1885 (fig. 1 and fig. 2). Depicting the narrow strip of beach visible from his hotel room, these are the only paintings from the 1885 campaign to show the stone building (possibly a customs warehouse) to the right of the hotel (and at the right edge in the paintings). This structure was still standing in 1920 when Henri Matisse painted it from a similar viewpoint in his painting, Les caloges, Étretat. Because the paintings do not share the same scale—The Departure of the Boats, Étretat is a size 30 portrait format, while Boats on the Beach at Étretat is smaller, a size 25 portrait, both turned horizontally—they are not pendants but instead a pairing, two works that share subject, season, vantage point, palette, and manner of conception (see Technical Reports, cat. 22, cat. 23). By this point in Monet’s career, once he had painted the essentials of a given motif, a critical second stage followed back in the studio, where the artist strived to align his compositions with his self-imposed aesthetic demands.

“My Caloges”

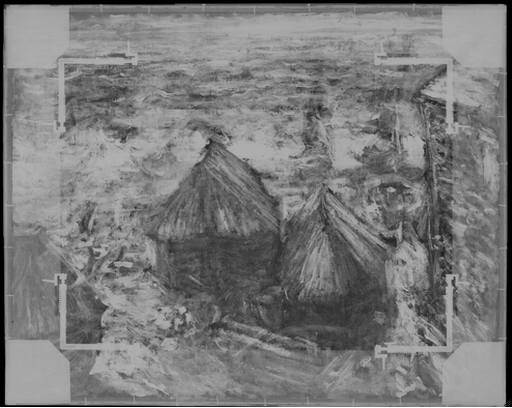

Monet painted the majority of his earlier (1883) boat and beachscape compositions from the beach or the stone dock (perrey, or perré); one exception is Fishing Boats (fig. 3 [W823]), which shows the same elevated viewpoint, roiling sea, and shoreline punctuated by boats as the 1885 compositions. It was also painted in bad weather, and from a window of the Hôtel Blanquet, although from a slightly different orientation and from a viewpoint that is closer to the sea than in the Art Institute paintings. In the foreground are caloges—old boat hulls that served as storehouses for nets and other fishing gear (fig. 4)—covered with thatch rather than the tarred planks of wood seen in the Art Institute’s versions. Technical images of Boats on the Beach at Étretat show that the dark, house-like structures, as well as the stone building at right, were part of the original composition, and unlike other motifs such as the boats, riggings, barrels, and winches, remained relatively untouched by alterations or overpainting (fig. 5; see also Technical Report, cat. 22).

As indicated in his November letter to Alice, Monet was particularly interested in the caloges that dotted the coast, retired crafts that represented the end of a seafaring career. Once beached, the caloges were recycled into giant containers and, in some cases, served as makeshift homes. In the Art Institute’s versions and in the 1883 Fishing Boats (fig. 3), these caloges serve as topographical and cultural indicators. The sailing vessels in Fishing Boats, for example, rock in front of the waves as if anxious to distance themselves from the straw-roofed, brooding premonitions of their future. In Fishing Boats at Étretat (fig. 6 [W825]), another 1883 composition taken from a slightly lower elevation overlooking the perrey, the working boat is beached side by side with a caloge, making clear their relationship and significance. Contemporary photographs of these imposing converted structures (see fig. 7) attest to the same close physical relationship with the working boats that Monet describes in his painting. These photographs also help to make sense of Monet’s vertical and horizontal strokes of color, seen in the two Art Institute canvases, which describe the system of parallel wood planks (possibly cabestans) that were used to haul the boats up the steep shingle beach to the dry dock (fig. 8).

Monet, who grew up on the Normandy coast in Le Havre, translated these elements of the fishing trade, rendering them as random, abstract shapes that are difficult to decipher without contemporary photographs as a guide. This is certainly the case with the forms at the far right of the smaller composition Boats on the Beach at Étretat (cat. 22), between the edge of the beach and the stone building, which have been interpreted as a winch with figures. [glossary:X-ray] and infrared photography (fig. 9) indicate that there was once a second winch to the left of the winch visible in the final composition, which Monet roughly and incompletely painted over. There are also unresolved forms to the right of the winch, which were ultimately painted over and are now the blocky rust-colored verticals in the final version. These blocky verticals remain a mystery, given that there is no other sign of human activity on the beach. Comparing the two rust-colored verticals (fig. 10), the leftmost of which covers already dried strokes of blue and red, to vertical strokes in The Departure of the Boats, Étretat (cat. 23) used to describe the crowd figures (fig. 11) raises the possibility that the rust-colored strokes may represent another winch post or timbers that had been pounded into the beach. But the underlying fragments of blue and red could also indicate that Monet originally intended a person to be placed near the winch.

Monet’s Genre Painting

In The Departure of the Boats, Étretat, the forms are unambiguous and clearly decipherable. And yet, apart from the larger and more detailed male figure appearing just to the left of the open door of the middle, largest caloge (fig. 12), the groups of men and women at the water’s edge (fig. 11 and fig. 13) are composed of calligraphic dashes. Even in these staccato-like groupings, for example, the figures at the far left along the beach in the Departure denote gender and perhaps even social class. In the group of figures on the left of the largest caloge, for example, the figure third from the left, under magnification, suggests an elegant woman wearing a wide-brimmed hat over a bodice with a shawl-collar and coordinating skirt (fig. 11). She and the other two-toned figures are fashionable onlookers, not the sturdy fishermen’s wives who often helped launch vessels and hand-winch them back onto the beach (see fig. 8). But the season for tourism had passed, and one wonders whether Monet inserted, rather than observed, these figures who mingle among the less-articulated strokes of paint that may be a nod to the jaunty male visitor clad in bright-blue knickerbocker suits coupled with the scarlet berets of the fishermen.

Patches of white and pink in front of the centermost caloge of both canvases suggest debris or other working materials. In Departure these are thickly impasted with pinks, whites, and blues, and appear as an abstracted floral arrangement perhaps in a net, with green, vine-like leaves trailing to the right (fig. 14). These forms paradoxically appear in the same area of Boats on the Beach (fig. 15) but are more clearly defined. In Departure the paints are dabbed on wet into wet, whereas in Boats on the Beach they are painted wet into wet with a few horizontal strokes and carefully outlined so that they appear to have a functional relationship to the nearby nets and barrels.

Method and Meaning

In contrast to the earlier 1883 compositions (fig. 3 and fig. 6), painted in more naturalistic browns, blues, and grays, the palette of both 1885 versions draws from the color mosaics of pinkish mauve, acidic yellows and creamy pinks, violets, and reds, which Monet had first experimented with in his Bordighera landscapes (see cat. 20) and that he would continue using throughout the 1880s (see cat. 24 and cat. 25). In both 1885 Étretat versions, for example, the tarred tops of the caloges appear as dark and undifferentiated but are actually made up of stripes of pastel blues, pinks, lavenders, and turquoise that paradoxically combine to suggest surfaces wet from the ocean fog and air on the overcast day (fig. 16 and fig. 17).

Writing about Boats on the Beach at Étretat in 1950, the art historian Lionello Venturi termed Monet’s palette “angry,” an adjective that more aptly fits his technique, with sketchy slashes as brushwork, quite at odds with the more even-handed paint application used for Departure of the Boats. X-ray images of both canvases reveal that the larger Departure was more planned out from the beginning, without the changes and repaints that give the smaller Boats on the Beach its improvisational quality. Compared to the roughly laid-in strokes of color in the smaller version, the brushwork in Departure is more contained, more regular. In the smaller composition, Monet’s vigorous reworking (or scraping down and repainting) [glossary:wet-on-wet] and [glossary:wet-over-dry] of the boats and the area between the building and caloge suggests spontaneity and passion (see Technical Report, cat. 22). This is corroborated by X-ray and infrared examinations, which show that the artist made and changed the same area at numerous stages of the painting’s buildup, often allowing the changes in color, line, and form to show through. The result of these decisions is a rough texture that seems preordained, as if Monet was trying to express the roughness of the conditions he transcribes, and the immediacy, the urgency needed to capture the uncontrollable changing atmospheric conditions as well as the movements of boats and sea.

Monet’s initial optimism, as noted in his November 24 letter to Alice about working indoors soon turned to frustration. Although his perch at the window of his hotel room allowed him a controlled environment in which to paint, he could not control his subject matter. Pentimenti visible to the unaided eye on the boats in Boats on the Beach at Étretat in particular suggest his responses to the constantly changing conditions, and, more importantly, the repositioning of the fishing boats and their masts as they were launched from and docked at the stony beach. It is unclear how much of the reworking to this canvas and to Departure of the Boats, Étretat was due to the variable natural effects, and how much was due to his reassessment of these works back in his Giverny studio. We are left with the scientific evidence and letters to tease out the real story behind this compelling, dramatic, and in many ways, metaphorical composition of these images: in Boats, suggesting the violence of nature, with turbulent weather crashing up onto the boats; and in Departure, showing the tranquil aftermath to inclement weather, with the sea filled with serenely placed boats ready for business with their sails hoisted.

Despite the differences in mood and handling, Monet centered both Boats on the Beach at Étretat and The Departure of the Boats, Étretat on “my caloges.” While there is a focus on the relationship of the boats, not only to the sea but also to these picturesque and permanently beached counterparts, it is the caloges—emblems of the coastal fishing culture, which evoke shelter and solidity—that were perhaps of most interest to Monet.

Gloria Groom