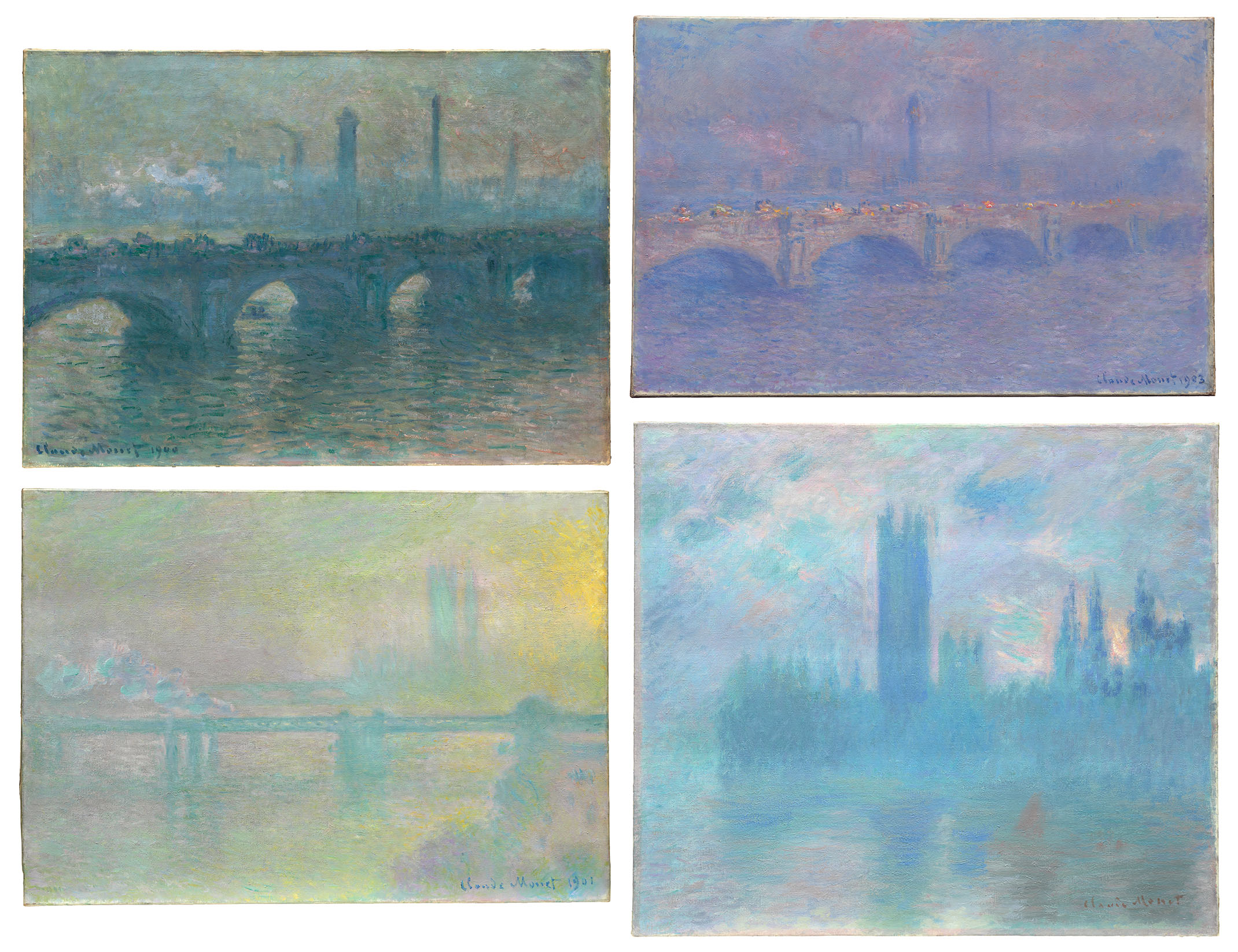

Cat. 38

Waterloo Bridge, Gray Weather

1900

Oil on canvas; 65.4 × 92.6 cm (25 3/4 × 36 3/8 in.)

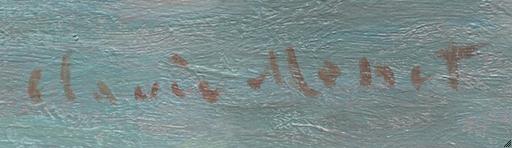

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 1900 (lower left, in a mixture of blue and green paints)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Mrs. Mortimer B. Harris, 1984.1173

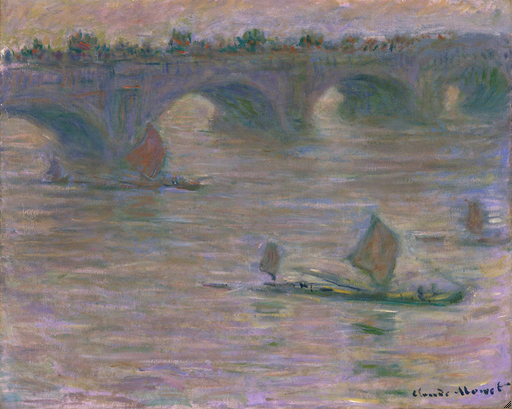

Cat. 39

Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect

1903

Oil on canvas; 65.7 × 101 cm (25 7/8 ×39 3/4 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 1903 (lower right, in blue paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1163

Cat. 40

Charing Cross Bridge, London

1901

Oil on canvas 65 × 92.2 cm (25 5/8 × 36 5/16 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 1901 (lower right, in blue paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1150

Cat. 41

Houses of Parliament, London

1900–01

Oil on canvas; 81.2 × 92.8 cm (32 × 36 9/16 in.)

Signed: Claude Monet (lower right, in light reddish-brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1164

London Calling

Over the course of three trips he made to London between autumn 1899 and spring 1901, Claude Monet began a series of works concentrating on a narrow range of the city’s sites: Waterloo Bridge (cats. 38–39), Charing Cross Bridge (cat. 40), and the Houses of Parliament (cat. 41). Although he started off this campaign confidently and methodically, it was not long before feelings of frustration overtook him, something that occurred during nearly every painting trip Monet had embarked on since the 1880s. In early March 1901, for example, he wrote to his second wife, Alice, about his trouble making progress on his London canvases: “As I’ve said before, it is not possible to work on the same paintings two days in succession. I’ll have to limit myself to concentrating only on studies and rough sketches so that I make something of them at my leisure in the studio.” Monet further complained, “It’s almost impossible to continue work on a painting. I make alterations to paintings and often ones that were passable are worse for the change. No one would ever guess the trouble I’d gone through to end up with so little.”

This was not the first time that Monet had visited or painted London. He waited out the Franco-Prussian War there from late summer 1870 to the spring of 1871, having fled France to avoid military service. It was during that initial stay—as exemplified in The Thames below Westminster (fig. 1 [W166])—that he tackled the unique effects of mist and fog that were characteristic of the city. Although he visited London a number of times over the ensuing years, it is difficult to pinpoint Monet’s motivation, after three decades, to return to the city for subject matter.

Art historians typically suggest that these paintings allowed Monet to satisfy a long-postponed desire to paint London’s fog, or that at this specific point in his life and career, it was “his recurrent wish to return to sites that he had painted many years before, as if to test out his art and his eye against his previous paintings and memories.” Indeed, in the 1890s Monet was interested in painting serially the effects of weather conditions, and he revisited a number of motifs and sites that he had painted earlier in his career, including the stacks of wheat (e.g., cats. 28–33) and locations along the Channel coast (e.g., The Customs House at Varengeville [cat. 35]) and the banks of the Seine (e.g., Branch of the Seine near Giverny [Mist] [cat. 36]). Art historian Paul Tucker agrees that these paintings reveal the aging Monet’s impulse to reinvent himself with a nod to his own past; he has further suggested that Monet’s return to London was partially instigated by the artist’s frustration toward his homeland in the wake of the Dreyfus Affair and by his ambition to secure a place in art historical memory for himself and the Impressionist agenda.

Tucker suggests that Monet, having witnessed at last the delayed acceptance of Impressionism in France, at this precise moment felt compelled to overcome his rivals elsewhere. England was the most important breeding ground for landscape painters in the nineteenth century, as embodied by artists such as John Constable and the more contemporaneous James McNeill Whistler, who was a friend of Monet’s. But above all it was J. M. W. Turner—whose Rain, Steam, and Speed—The Great Western Railway (fig. 2) Monet particularly admired—that Monet contended with. As noted by Tucker, Monet “was doing battle not just with nature but also with one of the finest painters to have confronted that fickle subject and successfully wrestled it into paint.”

The Subjects

In terms of volume, Monet’s London project surpassed all his previous series. In total, Monet produced nearly one hundred canvases and more than twenty-five pastels during the campaign. Each time he visited London over the course of the three-year period, Monet stayed at the Savoy, one of the finest hotels in the city located on the north bank of the Thames (see fig. 3). During the first campaign, from September through October 1899, Monet focused on Charing Cross Bridge, which he could see looking to the right from his hotel window. At this time, he may also have begun work on his depictions of Waterloo Bridge, visible to the left. It was only in the course of his second trip, from February 9 to April 5, 1900—upon obtaining permission to paint from the terrace of St. Thomas’s Hospital on the other side of the Thames—that he began painting Westminster Palace, which featured the Houses of Parliament with its imposing towers. Monet continued working on all three motifs during his third visit from late January to March 1901.

Although Monet selected a limited number of views for his London series, each work is differentiated by slight yet notable variations. In some depictions of Charing Cross Bridge, Monet included—as in the Art Institute’s canvas—a sliver of the Victoria Embankment at the bottom right. In other versions, such as one in the Baltimore Museum of Art (fig. 4 [W1532]), Monet shifted his gaze further to the left, eliminating the embankment altogether. When depicting the Houses of Parliament, Monet always included the distinctively square-shaped Victoria Tower, but by either zooming in or out or by looking left or right, Monet chose which parts of the Westminster towers appeared along the right edge of the canvas (see fig. 5 [W1609]). Monet was perhaps most experimental in his depictions of Waterloo Bridge—the subject that Monet painted the most (forty-one times in total). In both of the Art Institute’s two versions of the structure, Monet chose to include a varying number of arches and smokestacks. In other views, he tested out more extreme vantage points by changing the location of the bridge on his canvas (fig. 6 [W1584]).

On his second trip, Monet worked from his room at the Savoy for the first part of the day, and in late afternoon, he would go across the river to the hospital to paint the Houses of Parliament at sunset. Limited by the fleeting weather effects at different times of day, Monet began “studies and rough sketches” that he intended to rework in his Giverny studio rather than aiming for executing fully developed compositions on the spot. Nearing the end of his second trip, he described his frenzied working method to his wife Alice, and he expressed regret about the time he felt he had wasted: “Just imagine, I’m bringing back eight full crates, that’s eighty canvases, isn’t it frightening? And if I’d had the right idea in the first place and had started afresh each time the effect changed, I would have made more progress, instead of which I dabbled around and altered paintings that were giving me trouble.”

The Struggle

Bringing the canvases back to his Giverny studio, however, would not prove to be an antidote; two years later, Monet was still struggling with them. Writing in late March 1903 to his dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, about the plans for an upcoming exhibition, Monet anxiously described his predicament: “I can’t send you a single London painting since for this kind of work I need to be able to see them all, and quite honestly none of them are completely finished. I’m working on them all, or on a number of them anyway, and don’t yet know how many I’ll be able to exhibit, since what I’m doing is very delicate.” Just a few days later, he confessed to long-time supporter the art critic Gustave Geffroy that “my mistake has been to want to retouch them; one so quickly loses a good impression . . . those attempts and lay-ins could have been shown; but now that I have retouched all of them, I must at all costs go through to the end.”

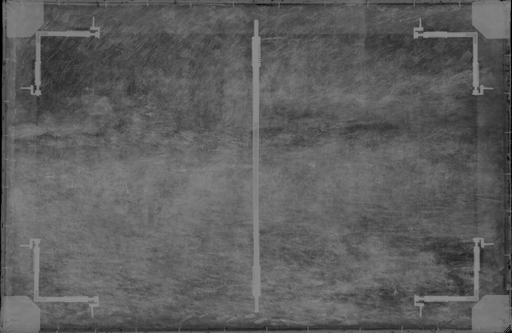

Unwilling to part with his London paintings, Monet was forced to delay exhibiting them until spring 1904. Indeed, hints of his battle with these canvases are evident throughout the Art Institute’s four London canvases. To varying degrees, the pictures all reveal signs of being worked and reworked, for the surfaces of each include texture from brushstrokes that Monet applied in earlier painting sessions and subsequently painted over. It is impossible to determine precisely when he made these changes, however, for the dates that Monet assigned to his London paintings range from 1899 to 1905. And, as revealed by the Art Institute’s Houses of Parliament and Charing Cross Bridge, there is evidence that Monet presumably changed his mind about when he considered these paintings finished. In Houses of Parliament, Monet signed the painting at lower right, but subsequently reworked the water in that area, covering the signature, which required him to re-sign the painting virtually on top of where it originally appeared (fig. 7). Charing Cross Bridge reveals a more significant change; it was once signed at bottom left (fig. 8), but Monet later obliterated his autograph and re-signed and dated it at bottom right, the location where he consistently inscribed most of the Charing Cross Bridge paintings that included part of Victoria Embankment at bottom right (see Signature in the technical report).

Aside from changing the placement of his signature, Monet made major compositional changes to Charing Cross Bridge. Transmitted-light imaging reveals that the main vertical elements in the painting—the bridge supports, the Houses of Parliament, and the embankment—were moved further to the right in the final composition (see Paint Layer in the technical report). It also suggests that the Art Institute’s version may have originally been laid in much more like the Baltimore painting (fig. 4), which is the clearest, most complete view of Charing Cross Bridge in the series, and includes Westminster Bridge and the Lambeth suspension bridge in the background. In the Chicago picture, the faint presence of Westminster Bridge is indicated, but technical images suggest that the bridge was initially more pronounced and expansive, suggesting Monet began this painting as a wider and more precise panoramic vista that he then reworked and obscured as he developed the enveloppe of fog.

Technical imaging also indicates that significant changes appear in the Art Institute’s Waterloo Bridge, Gray Weather, in which Monet dramatically altered the angle of the bridge and the number of arches, in addition to varying the position of the smokestacks (fig. 9). The Art Institute’s other Waterloo Bridge picture, Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect, on the other hand, does not show evidence of pentimenti (fig. 10), although this is perhaps due to densely applied paint, making it difficult to see if Monet made changes. What is particularly unique about Sunlight Effect is that the canvas Monet used was not one of the ones he brought with him and was probably one that he purchased there. The artist was running out of supplies; in March 1900, he wrote to his wife that “the only shortage I have is of canvases, since it’s the only way to achieve something, get a picture going for every kind of weather, every colour harmony, it’s the only way . . . I’m not lacking for enthusiasm as you can see, given that I have something like 65 canvases covered with paint and I’ll be needing more since the place is quite out of the ordinary; so I’m going to order some more canvases.” Indeed, as has been identified in recent technical examinations, this canvas—bearing traces of the stamp of Lechertier Barbe Ltd., a French canvas supplier with a branch in London at the time—is the coarsest of all thirty-three paintings in the Art Institute’s collection (see Support in the technical report).

When Monet eventually exhibited thirty-seven works from his London series at Durand-Ruel’s Paris gallery in 1906, they were a great success, both financially and critically. Durand-Ruel alone purchased eighteen of the works at the outset of the exhibition; the show was extended for three additional days; and there was discussion of staging a similar exhibition in London, although it never materialized. Critics, too, were hugely enthusiastic, and Monet was certainly pleased that a number of them mentioned the connection between his works and those of Turner. As described by critic Gustave Kahn, for example, “one might place certain Monets beside certain Turners. One would thereby compare two branches . . . of Impressionism, or rather . . . it would integrate two moments in the history of visual sensitivity.” But as evidenced in the Art Institute’s paintings from the London series, this acclaim was hard won. Monet labored intensively over these compositions and struggled to balance his direct, firsthand observations of the motifs with his desire to finalize his compositions and meticulously harmonize color effects in the studio setting.

Jill Shaw