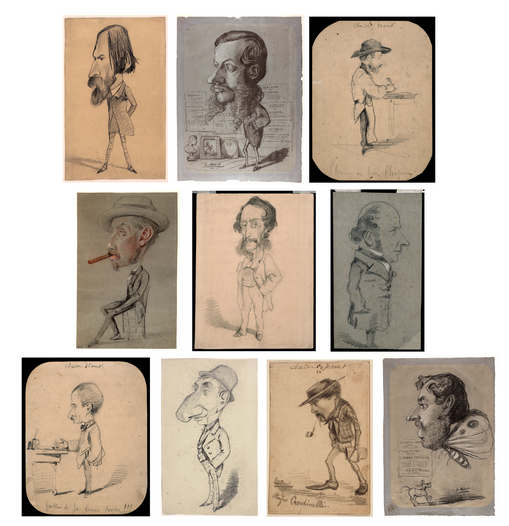

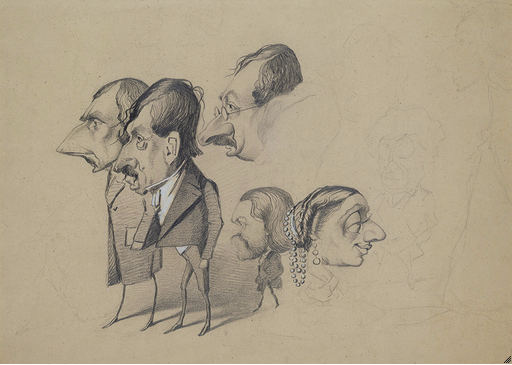

Cat. 1

Caricature of Auguste Vacquerie

c. 1859

Graphite with erasure on tan wove paper; 284 × 176 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.897

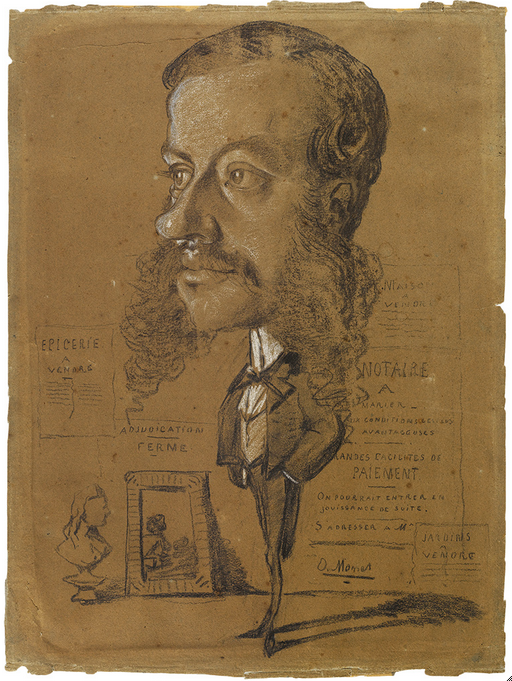

Cat. 2

Caricature of Léon Manchon

1858

Charcoal, with stumping and heightened with white chalk, on blue laid paper (partially discolored to yellowish gray); 612 × 452 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.888

Cat. 3

Caricature of a Man in a Small Hat

1855/56

Graphite on commercially prepared cream wove card (discolored to tan); 198 × 149 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.892

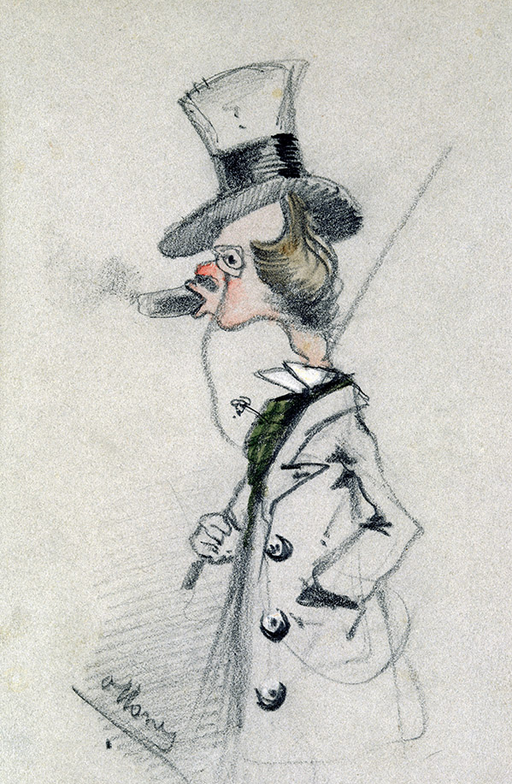

Cat. 4

Caricature of a Man with a Big Cigar

1855/56

Black and red chalk, with touches of colored chalks, on blue wove paper (discolored to blue-gray), laid down on cream wove paper, laid down on blue wove paper; 598 × 385 mm (primary/secondary/tertiary supports)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.890

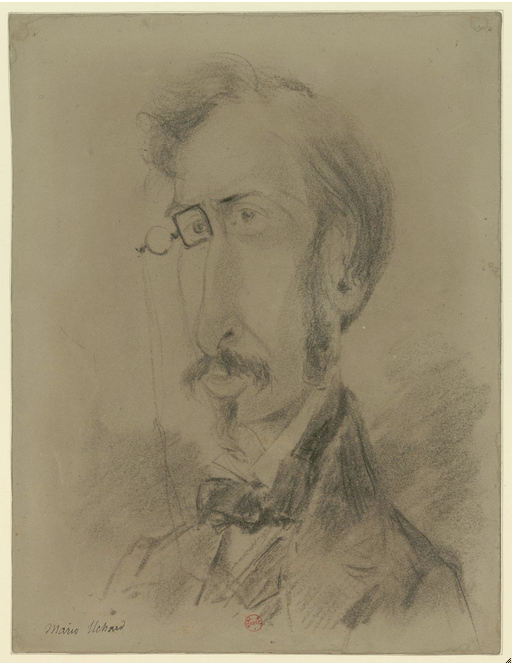

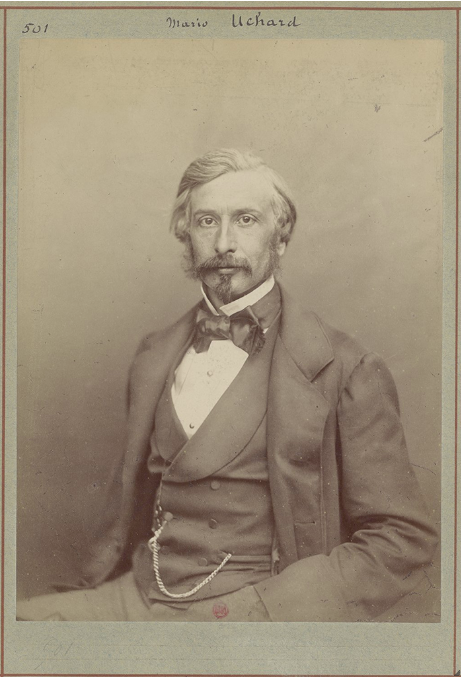

Cat. 5

Caricature of Mario Uchard

c. 1858

Graphite with touches of erasure and stumping on tan wove paper; 320 × 245 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.891

Cat. 6

Caricature of Eugène Marcel

1855/56

Graphite, heightened with white chalk, on gray wove paper; 239 × 136 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.896

Cat. 7

Caricature of a Man Standing by a Desk (recto)

1855/56

Graphite on commercially prepared ivory wove card (discolored to tan); 203 × 166 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.894R

Sketch of a Male Head in Profile (verso)

1855/56

Graphite on commercially prepared ivory wove card; 202 × 165 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.894V

Cat. 8

Caricature of a Man with a Large Nose

1855/56

Graphite on greenish-gray wove paper; 248 × 152 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.895

Cat. 9

Caricature of Henri Cassinelli (“Rufus Croutinelli”)

c. 1858

Graphite on commercially prepared tan wove card; 130 × 85 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.893

Cat. 10

Caricature of Jules Didier (“Butterfly Man”)

c. 1858

Charcoal, heightened with white chalk, with smudging, on blue laid paper (discolored to light brown); 616 ×436 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection, 1933.889

Early Caricatures

Biting and amusing by turns—and visually surprising, given the Impressionist touch for which the artist is best known—Monet’s caricatures form an idiosyncratic chapter of his oeuvre. He drew them as a youth and, significantly, they are probably the first works for which he received payment. For many years, art historians and dealers tended to dismiss the drawings, considering them somewhat anecdotal. However, as James A. Ganz and Richard Kendall argue in a recent publication, the caricatures reveal much of the artist’s early interests and ambitions. They are visually engaging and, quite tellingly, help to situate the artist at a particular historical moment.

The first mention of the caricatures in print appeared in 1883, in an article by the critic, printmaker, and collector Philippe Burty, who wrote positively about Impressionist art. Burty explained how, on leaving school, the young artist tired of helping out in his father’s business. In order to earn money of his own, “Monet drew caricatures with huge heads (like those made fashionable by Daumier’s Representatives Represented) of the regulars at the harbor cafés, the brokers and captains of the casual trade. He would supply himself with vellum, pencils, and penknives at Boudin’s stationary store. The owner . . . even framed these caricatures [to sell in his shop], appreciating their allure while finding the drawing technique somewhat insufficient.”

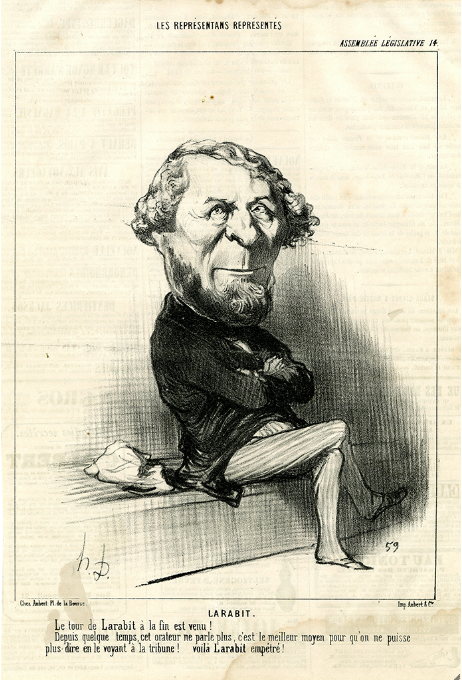

Burty’s allusion to The Representatives Represented was astute. Typically, Daumier had not distorted the features of the figures he depicted to any great extent; but he had given them disproportionately large heads for their bodies (see fig. 1). Quite logically, if Monet awarded his figures a similar physique, he may have hoped for comparable success. In the 1850s, when the young artist made his caricatures, Daumier’s work was popular and accessible.

That images such as The Representatives Represented circulated readily in the mid-nineteenth century is unsurprising. There were plenty of outlets for satirical art. Cheaper methods of reproduction had led to a proliferation of new periodicals in France. Popular ones—such as L’illustration—printed more than one hundred thousand copies per week. There were journals and magazines for all social classes and political persuasions, and it was typical for a bourgeois family to enjoy such publications. Prompted by material of this kind, the young artist made copies after some of the leading caricaturists of the day (including Nadar, Étienne Carjat, and Paul Hadol). Concurrently, he made original caricatures, perhaps commissions from the local figures they parody. However, since some authors consider that the copying process constituted an apprenticeship of sorts, it seems logical to address Monet’s drawings that fall into that category first.

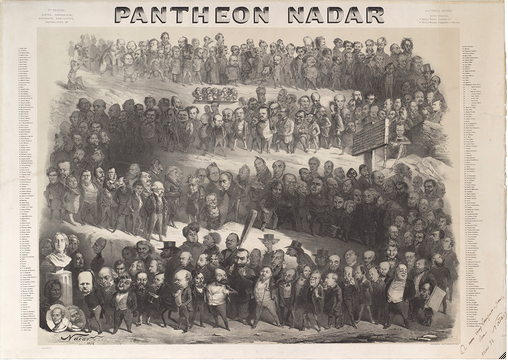

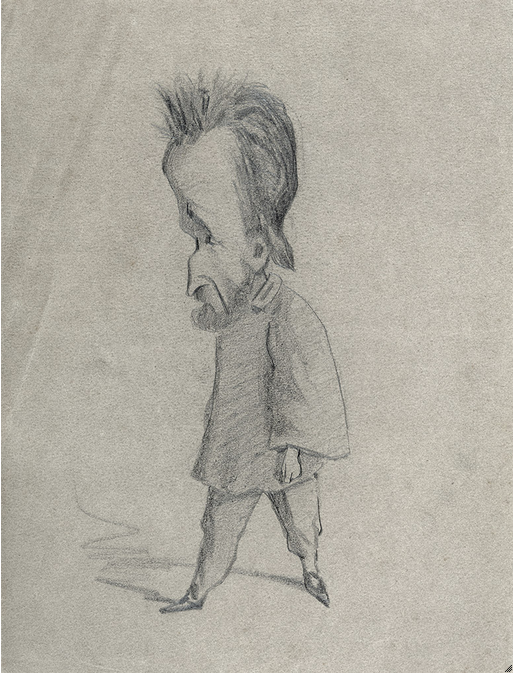

It was Pierre Georgel who first recognized, in 1968, that one of the Art Institute’s caricatures, Auguste Vacquerie (cat. 1 [D505]), was not an original composition but a visual quotation from the ambitious Panthéon Nadar of 1854 (see fig. 2). This well-known work featured representations of around three hundred figures from French cultural life. Among its line-up were such notables as Honoré de Balzac and Alexandre Dumas. On other occasions, most probably around the same time, Monet copied different figures from the Panthéon. His portrait-charge of the journalist Théodore Pelloquet, now in the Musée Marmottan Monet, is one such example (see fig. 3).

The young artist evidently admired Nadar’s idiosyncratic arrangement of heads—he mimicked the domino-like composition in his Petit Panthéon théâtral (fig. 4)—but in this particular instance he had motives other than emulation. One of the figures portrayed, Auguste Vacquerie, was a writer from Le Havre who had proven himself a loyal follower of Victor Hugo in the most literal of terms. When Hugo left France to avoid arrest, having criticized Napoleon III, Vacquerie went with him to the Channel Islands. Nonetheless, though physically estranged from France, Vacquerie’s local reputation ensured he remained topical in his hometown. Indeed, Monet had particular cause for interest, as his father had ties with the Vacquerie family. Coupled with the comic appeal of the writer’s features (Vacquerie—by his own admission—had a rather large nose), it is clear he made a particularly compelling subject (see fig. 5).

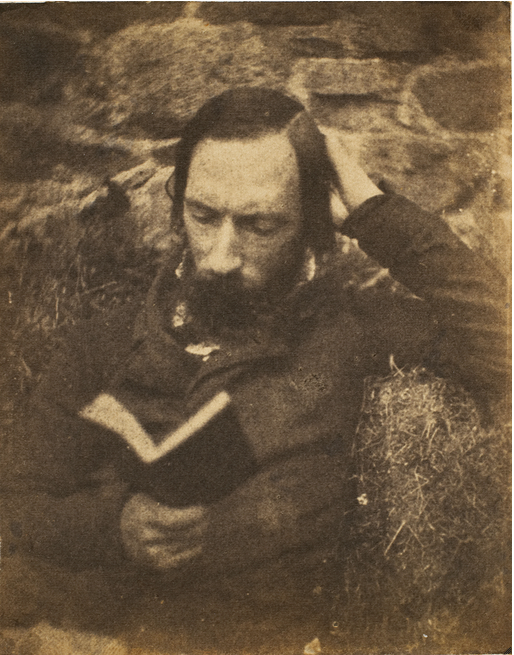

This would suggest that, as much as he chose his models for aesthetic reasons, Monet’s selections were personality driven. Nadar had depicted the playwright Mario Uchard (see fig. 6) and even photographed him in later years (see fig. 7); but Monet took his portrait-charge of Uchard (cat. 5 [D499]) from a caricature by Carjat. Of course, convenience may have shaped the choice, and Monet could simply have seen the work as it appeared in the right-wing newspaper Le gaulois. But, beyond that, it is possible he appreciated Carjat’s visual description of this controversial character. Uchard had recently satirized his personal life in a play staged at the Théâtre Français; the actress Madeline Brohan (his partner, whom it portrayed in an unflattering light) was absent at the time. In view of his notoriety, then, the caricature’s confrontational stance in the portrait-charge seems entirely appropriate. A monocle draws attention to his unflinching gaze. By choosing an image of a press-worthy literary figure to hone his talent, Monet may well have hoped that his own caricatures might one day find publishers. As it happened, he would have to wait until 1860 before one of his drawings appeared in print.

The practice of copying caricatures did serve a more pressing purpose in that, most probably, it informed how Monet described physiognomic detail. For instance, the thick fringe that curls around Uchard’s face—made with heavy continuous lines—is similar to that which appears in Caricature of Léon Manchon, a highly worked original Monet caricature in the Art Institute’s collection (cat. 2 [D481]). In both instances, he placed a blunt line below the lower lip, a shorthand of sorts for shadow.

When it came to making original caricatures, as in this instance, Monet probably knew his subjects personally. At Le Havre’s Société des Amis des Arts, where he showed his first documented painting, Manchon (see fig. 8) was treasurer. Tellingly, the framed pictures and portrait bust in the background of the image might refer to that context, as they suggest the staging of an exhibition. The signs, however, allude to the sitter’s work as a notary. “Grocer’s shop for sale” reads one; another alludes to his availability for weddings and a range of payment options.

A variant of this composition exists in the collection of the Beaux-Arts in Rouen and indicates how, on occasion, Monet experimented with different versions of the same caricature. It is difficult to tell in this instance which of the drawings came first but, given the higher degree of resolve in the costume of the Rouen figure and the confident white highlights, it seems likely that it developed from the Art Institute version. Nonetheless, it is likely he was pleased with both, since he cared to sign each one.

Of all Monet’s caricatures, copied or original, Caricature of Jules Didier (cat. 10) is the most fanciful. A bearded head, tethered by a female centaur, sits atop a winged insect body; the arrangement is particularly curious. Daniel Wildenstein identified Didier (fig. 9) as its subject. This now-forgotten academic painter won the Prix de Rome in 1857 and apparently specialized in landscape scenes. However, the rationale for the peculiar iconography remains a mystery, and so the issue continues to attract debate. Notably, for instance, Didier’s conventional works—a few of which remain in the collection of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris—shed no light on the peculiar iconography.

The poster in the background of Caricature of Jules Didier seems to relate to a fair or circus of some kind. It mentions a “Canon-man” and a “Butterfly man”: a line-up that, according to one recent reading, might cast the mention of ticket prices in the image (“prix des places”) as a snide reference to Didier’s popular success. Reined in by the classical beast, so the argument follows, the butterfly artist cannot fly free to fulfill his creative potential. However, unless further material comes to light to substantiate Monet’s thoughts on Didier, this thesis will remain speculative.

Other caricatures Monet created at this moment, the identities of the sitters often unrecorded, lack the nuanced detail of those with professional precedents. The lines of Caricature of a Man with a Large Nose (cat. 8 [D492]) are lighter and less decisive than those in the works after Nadar and Carjat, for instance, while the description of the figure’s clothing is relatively vague. The execution of Caricature of a Man in a Small Hat (cat. 3 [D496]) and Caricature of Eugène Marcel (cat. 6 [D491]) also seem relatively casual. The trousers of the former are shaded with rough diagonal pencil strokes; his right hand—which clutches an instrument of some kind—is barely resolved. Perhaps for the sake of speed, in the latter he hid the subject’s hand in the pocket of his coat. In Caricature of a Man Standing by Desk (cat. 7 [D497]), meanwhile, the artist left his revisions of the jacket shape in evidence, and the furniture looks anything but steady.

Arguably, with its touches of color, Caricature of a Man with a Big Cigar (cat. 4 [D490]) is the most compelling of the anonymous group. It is more finely detailed than many of Monet’s original compositions and, unusually, makes use of red chalk in areas that include the figure’s ruddy cheeks and the creases of his brow. The lines of the sitter’s suit are sharp and his collar consists of a few clean touches of white. However, if the execution of Caricature of a Man with a Big Cigar is sensitive, the overall effect is comic. The subject has overly long legs. His curved eyelashes border on the feminine.

The body language Monet described in the last of the Art Institute’s original caricatures, Caricature of Henri Cassinelli (“Rufus Croutinelli”) (cat. 9 [D495]) stands in stark contrast to the elegant pose of the figure in Dandy with a Cigar (fig. 10). Here the subject’s entire demeanor is pitiful: from his downcast eyes to his hand in pocket—even his waxed mustache seems to droop despondently. This dejected character was apparently a fellow applicant for municipal funding whom Monet satirized in a portrait-charge. In a play on the word croute, as in “daub,” he renamed his huddled rival “Rufus Croutinelli.” Henri Cassinelli was a bad painter, he implied, whose appearance was as hopeless as his art.

Though Monet used his image to mock Cassinelli’s artistic struggle, this was also a difficult period in his own professional development. At this stage, though his caricatures brought him notoriety, they also proved a hindrance. In response to Monet’s own grant application, the authorities cast doubt on his aptitude for more serious artistic endeavor. “Through caricature . . . ,” read their report, “Monet has already found the popularity that comes so slowly to serious works. But with his precocious success is there not a danger, that in following the facile path of his pencil the young artist might be kept from the more serious and thankless studies that alone justify municipal liberality? Time will tell.”

Clearly, as history has proven, Monet had the last laugh. In later life, with discernable glee, he boasted of his youthful commercial prowess: “At fifteen, all of Le Havre knew me as a caricaturist . . . the plentiful commissions . . . prompted me to make an audacious decision that, of course, would scandalize my family. I took payment for my portraits. Depending on the look of a person, I’d charge them between ten and twenty francs for their portrait, and the scheme served me marvelously. My clients doubled in a month. I was able to set a fixed price of twenty francs without slowing down orders at all. If I’d have carried on, today I’d be a millionaire.”

Quite reasonably, doubts have been raised as to just how much money Monet could have earned through his efforts; there are evident inconsistencies in the artist’s recollections of his early career, and he tended to exaggerate his talent. Nonetheless, poetic license aside, the caricatures give reliable insight into the artist’s beginnings in Le Havre. The Art Institute’s group—one of the most significant in a single public collection—are representative of their range and complexity.

Nancy Ireson