Selected References

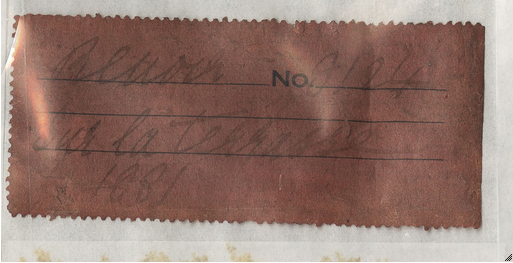

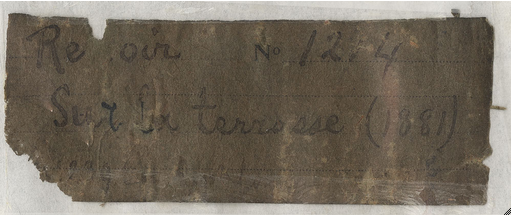

Ernest Hoschedé, L’art de la mode (1881), (ill.).

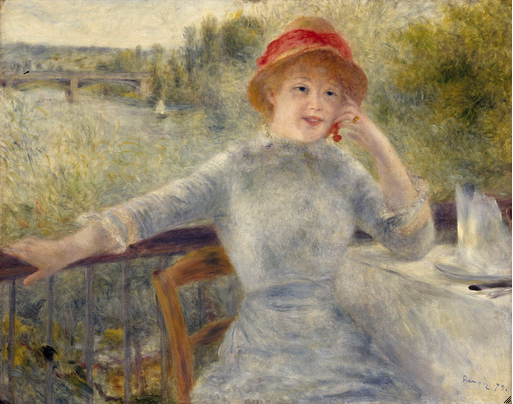

Catalogue de la 7me exposition des artistes independants, exh. cat. (Morris Pére et Fils, 1882), cat. 138.

La Fare, “Exposition, des impressionnistes,” Le gaulois, Mar. 2, 1882, p. 2.

Henry Havard, “Exposition des artistes indépendants,” Le siécle, Mar. 2, 1882, p. 2.

A. Hustin, “L’exposition des peintres indépendants,” L’estafette, Mar. 3, 1882, p. 3. Reprinted in Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), p. 395.

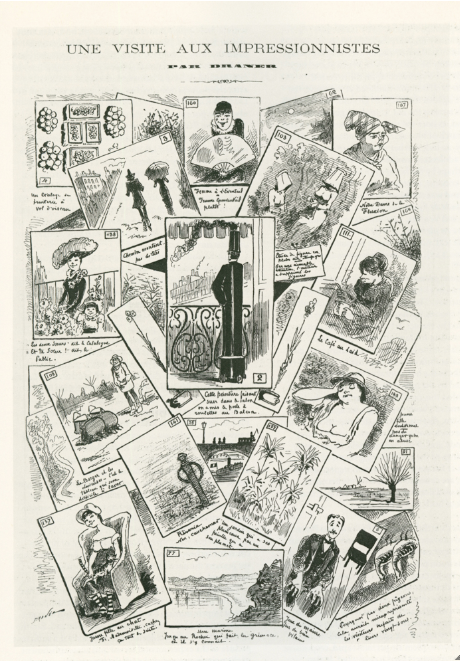

Draner, “Une visite aux impressionnistes,” Le charivari, Mar. 9, 1882, p. 3. Reprinted in Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 386, 417.

A. Hustin, “L’exposition des impressionnistes,” Moniteur des arts (Mar. 10, 1882), p. 1. Reprinted in Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), p. 396.

Durand-Ruel, Catalogue de l’exposition des oeuvres de P.-A. Renoir, exh. cat. (Pillet & Dumoulin, 1883), p. 12, cat. 30.

Ph. B. [Philippe Burty], “Les peintures de M. P. Renoir,” La republique française (Apr. 15, 1883), p. 3.

American Art Association, Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, exh. cat. (J. J. Little/American Art Galleries, 1886), p. 31, cat. 181.

American Art Association, Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, exh. cat. (National Academy of Design, 1886), p. 45, cat. 181.

Georges Lecomte, L’art impressionniste d’après la collection privée de M. Durand-Ruel (Chamerot & Renouard, 1892), pp. 137 (ill.), 204, 207.

Durand-Ruel, Paris, Exposition A. Renoir, exh. cat. (Imp. de l’Art/E. Ménard, 1892), pp. 33; 34; 46, cat. 92.

Richard Muther, The History of Modern Painting, vol. 2 (Henry, 1896), p. 748 (ill.).

Durand-Ruel, Paris, Exposition de tableaux de Monet, Pissarro, Renoir & Sisley, exh. cat. (Imp. de l’Art, 1899), p. 11, cat. 81.

Camille Mauclair, “L’oeuvre d’Auguste Renoir,” L’art décoratif 41, pt. 1 (Feb. 1902), pp. 173 (ill.), 179.

Camille Mauclair, “L’oeuvre d’Auguste Renoir,” L’art décoratif 42, pt. 2 (Mar. 1902), p. 224.

Camille Mauclair, The Great French Painters and the Evolution of French Painting from 1830 to the Present Day, trans. P. G. Konody (E. P. Dutton, [1903]), pp. 112, 114 (ill.).

Wynford Dewhurst, Impressionist Painting: Its Genesis and Development (Newnes, 1904), p. 52.

Maurice Hamel, “Le salon d’automne,” Les arts 35 (Nov. 1904), p. 35 (ill.).

Camille Mauclair, L’impressionnisme: Son histoire, son esthétique, ses maîtres, 2nd ed. (Librairie de l’Art Ancien et Moderne, 1904) pp. 112, 137–138. Translated by P. G. Konody as The French Impressionists (1860–1900) (Duckworth/E. P. Dutton, [1903]), pp. 120, 124.

Octave Maus, Exposition des peintres impressionnistes, exh. cat. (Libre Esthétique, 1904), p. 43, cat. 130.

Léon Plée, “Le salon d’automne,” Les annales politiques & littéraires 43, 1113 (Oct. 23, 1904), pp. 257; 261; (ill.).

Société du Salon d’Automne, Catalogue de peinture, dessin, sculpture, gravure, architecture et arts décoratifs, exh. cat. (Hérissey, 1904), p. 114, no. 12.

Grafton Galleries, Pictures by Boudin, Cézanne, Degas, Manet, Monet, Morisot, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, Exhibited by Messrs. Durand-Ruel & Sons, exh. cat. (Strangeways and Sons, 1905), p. 22, cat. 239.

Grafton Galleries, A Selection from the Pictures by Boudin, Cézanne, Degas, Manet, Monet, Morisot, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley (Durand-Ruel and Sons, 1905), p. 35, cat. 239 (ill.).

Henry Morison, “Auguste Renoir, Impressionist,” Brush and Pencil 17, 5 (May 1906), pp. 201, 203.

British Art Committee, Souvenir of the Fine Art Section, Franco-British Exhibition, 1908, Complied by Sir Isidore Spielmann (Bemrose & Sons, 1908), pp. 101; 309.

Franco-British Exhibition, Catalogue of the Fine Art Section, 4th ed., exh. cat. (Bemrose and Sons, 1908), p. 181, no. 397.

Vittorio Pica, Gl’impressionisti francesi (Istituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche, 1908), pp. 84 (ill.), 98.

Arsène Alexandre, “Exposition d’art moderne á hotel de la revue ‘Les arts,’” Les arts 128 (Aug. 1912), pp. 5, no. 7 (ill.); 12.

Moderne Galerie Heinrich Thannhauser, Ausstellung Auguste Renoir, exh. cat. (R. Piper, [1912]), cat. 9.

Manzi, Joyant & Cie, Exposition d’art moderne, exh. cat. (Manzi, Joyant, 1912), cat. 180.

Bernheim-Jeune, Renoir, with a preface by Octave Mirbeau (Bernheim-Jeune, 1913), p. 19.

Zürcher Kunsthaus, Französische Kunst des XIX. u. XX. Jahrhunderts, exh. cat. (Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 1917), p. 24, cat. 169.

Ambroise Vollard, Tableaux, pastels & dessins de Pierre-Auguste Renoir, vol. 1 (A. Vollard, 1918), pp. 84, no. 334 (ill.); 177.

Georges Lecomte, “L’oeuvre de Renoir,” L’art et les artistes 4, 14 (Jan. 1920), pp. 146, 147 (ill.).

Willy Burger, “August [sic] Renoir,” Die Kunst für Alle 35 (Feb. 9/10, 1920), p. 169 (ill.).

Georges Rivière, Renoir et ses amis (H. Floury, 1921), opp. p. 134 (ill.).

Durand-Ruel, Paris, Tableaux pastels-dessins par Renoir, exh. cat. (Imp. de l’Art, 1920), cat. 52.

Paul Jamot, “Renoir (1841–1919),” Gazette des beaux-arts 8, 5, pt. 2 (Dec. 1923), pp. 323, 325 (ill.).

François Fosca, Renoir (F. Rieder, 1923), pp. 20; 62; pl. 25. Translated by Hubert Wellington as Renoir, Masters of Modern Art (Dodd, Mead, 1924), pp. 5; 21–22; pl. 18.

Ambroise Vollard, Renoir: An Intimate Record, trans. Harold L Van Doren and Randolph T. Weaver (Knopf, 1925), p. 240.

Royal Cortissoz, Seven Paintings by Renoir (Durand-Ruel, c. 1923), pp. 7, 8, 9, 22–23 (ill.).

Royal Cortissoz, Personalities in Art (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), pp. 279, 281, 282.

Royal Cortissoz, “Auguste Renoir and the Cult for Beauty,” International Studio 90, 375 (Aug. 1928), p. 20.

Julius Meier-Graefe, Renoir (Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1929), p. 142, no. 119 (ill.).

Carroll Carstairs, “Renoir,” Apollo 10, 55 (July 1929), p. 36 (ill.).

Royal Cortissoz, The Painter’s Craft (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1930), p. 233.

Reginald Howard Wilenski, French Painting (Hale, Cushman & Flint, 1931), p. 262.

“On the Terrace: From a Painting by August [sic] Renoir,” Christian Science Monitor 24, 201 (July 22, 1932), p. 7 (ill).

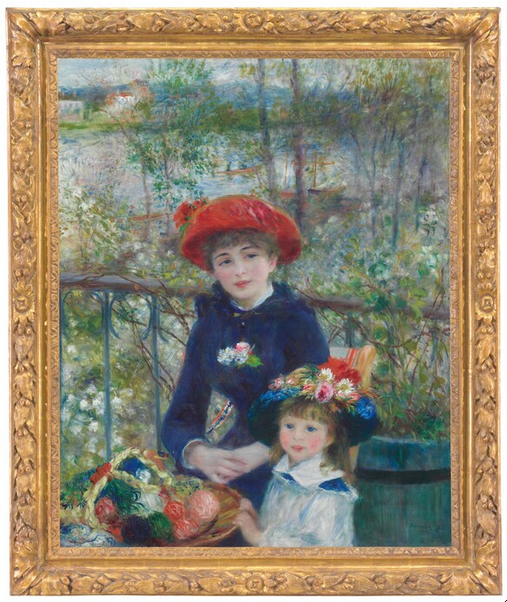

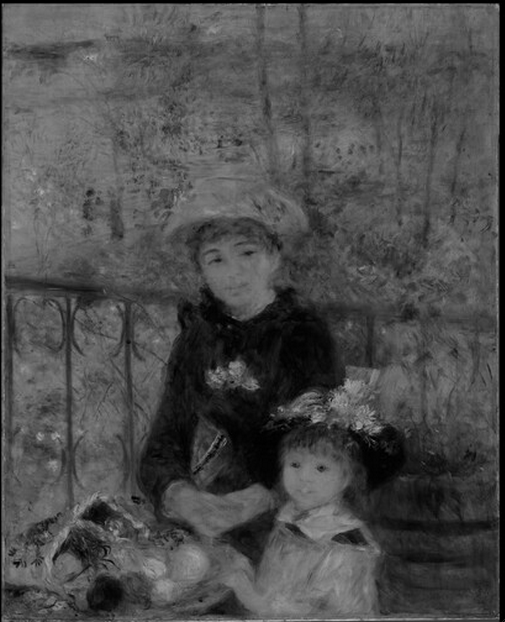

Daniel Catton Rich, “The Bequest of Mrs. L. L. Coburn,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 26, 6 (Nov. 1932), pp. 67 (ill.), 68.

Art Institute of Chicago, Exhibition of the Mrs. L. L. Coburn Collection: Modern Paintings and Watercolors, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1932), pp. 6; 23, no. 33; 51, no. 33 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1933), pp. 49–50, cat. 348.

Art Institute of Chicago, Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago, Report for the Year Nineteen Hundred Thirty-Two 27, 3, pt. 2 (Mar. 1933), p. 22 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “The Century of Progress Exhibition of the Fine Arts,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 27, 4 (Apr.–May 1933), p. 67.

Art Institute of Chicago, “The Rearrangement of the Paintings Galleries,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 27, 7 (Dec. 1933), p. 115.

Daniel Catton Rich, “Art in Chicago,” Vogue 82, 2 (July 15, 1933), p. 38 (ill.).

Daniel Catton Rich, “The Exhibition of French Art: ‘Art Institute’ of Chicago,” Formes 33 (1933), (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, 1934, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1934), p. 40, cat. 237.

Clarence Joseph Bulliet, Art Masterpieces in a Century of Progress Fine Arts Exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, vol. 2 (Chicago Daily News/North-Mariano Press, 1933), no. 116 (ill.).

Toledo (Ohio) Museum of Art, French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, exh. cat. (Toledo Museum of Art, 1934), cat. 15.

Albert C. Barnes and Violette de Mazia, The Art of Renoir (Minton, Balch, 1935), pp. 77; 78; 79; 83; 84; 86; 270, no. 119 (ill.); 405–06, no. 119; 453.

Claude Roger-Marx, Renoir, Anciens et Modernes (H. Floury, 1937), p. 85 (ill.).

Durand-Ruel, New York, Views of the Seine by Monet, Pissaro, Renoir, Sisley, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, 1937), cat. 6 (ill.).

Yale University Gallery of Fine Arts, An Exhibition of French Paintings of the Nineteenth Century, exh. cat. (Yale University Press, 1937), cat. 1.

Henry McBride, “The Renoirs of America: An Appreciation of the Metropolitan Museum’s Exhibition,” Art News 35, 31 (May 1, 1937), pp. 60, 73 (ill.).

Théodore Duret, Renoir, trans. Madeleine Boyd (Crown, 1937), pl. 3.

Lionello Venturi, Les archives de l’impressionnisme: Lettres de Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Sisley et autres; Mémoires de Paul Durand-Ruel; Documents, vol. 2 (Durand-Ruel, 1939), p. 268.

Reginald Howard Wilenski, Modern French Painters (Reynal & Hitchcook, [1940]), opp. p. 39, pl. 12; p. 8.

Charles Terrasse, Cinquante portraits de Renoir (Librairie Floury, 1941), p. 6; pl. 22.

Duveen Galleries, Renoir: Centennial Loan Exhibition, 1841–1941; For the Benefit of the Free French Relief Committee (Vilmorin/Bradford, 1941), pp. 57, cat. 35 (ill.); 139, cat. 35.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Department of Reproductions,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 38, 2 (Feb. 1944), p. 28.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Department of Reproductions,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 38, 5 (Sept.–Oct. 1944), p. 85.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Department of Reproductions,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 38, 7 (Dec. 1944), p. 116 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, An Illustrated Guide to the Collections of the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1945), p. 36.

“Chicago Perfects Its Renoir Group,” Art News 44, 16, pt. 1 (Dec. 1–14, 1945), p. 18.

Hans Huth, “Impressionism Comes to America,” Gazette des beaux-arts 29 (1946), p. 239, n. 22.

Louis Zara, ed., Masterpieces, Home Collection of Great Art 1 (Ziff-Davis, 1950), cover (ill.), pp. 4, 117.

Art Institute of Chicago, Masterpieces in the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1952), (ill.).

Charles Fabens Kelley, “Chicago: Record Years,” Art News 51, 4 (June–Aug. 1952), p. 54 (ill.).

Dorothy Bridaham, Renoir in the Art Institute of Chicago (Conzett & Huber, 1954), front cover; pl. 5.

M. K. R., “An Exhibition for Paris,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 49, 2 (Apr. 1955), p. 29.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Notes,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 50, 3 (Sept. 15, 1956), p. 59.

Wildenstein, Renoir: A Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York City, Inc. (Gallery Press, 1958), p. 45, no. 31 (ill.).

François Fosca, Renoir: L’homme et son oeuvre (A. Somogy, 1961), pp. 85, 117 (ill.), 281. Translated by Mary I. Martin as Renoir, His Life and Work (Prentice-Hall, 1962), pp. 85, 113 (ill.), 269.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), pp. 283 (ill.), 396–97.

René Gimpel, Journal d’un collectionneur, marchand de tableaux (Calmann-Lévy, 1963), pp. 181, 225. Translated by John Rosenberg as Diary of an Art Dealer (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966), pp. 157, 212.

Walter Pach, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Library of Great Painters (Abrams, [1964]), pp. 70–71 (ill.).

Frederick A. Sweet, “Great Chicago Collectors,” Apollo 84 (Sept. 1966), p. 203.

Charles C. Cunningham, Instituto de arte de Chicago, El mundo de los museos 2 (Editorial Codex, 1967), pp. 12, ill. 33 and ill. 34; 58, fig. 3; 59 (detail).

André Parinaud, Art Institute of Chicago, Grands musées 2 (Hachette-Filipacchi, [1968]), pp. 36, ill. 3; 37 (detail); 69, ill. 33 and ill. 34.

Elda Fezzi, Renoir (Sadea/Sansoni, 1968), pp. 21; 36; fig. 31. Translated into French by Simone de Vergennes as Renoir, Les petits classiques de l’art (Flammarion, 1969), p. 34; pl. 31.

Charles C. Cunningham and Satoshi Takahashi, Shikago bijutsukan [Art Institute of Chicago], Museums of the World 32 (Kodansha, 1970), pp. 48, pl. 34; 49, pl. 35 (detail); 159.

John Maxon, The Art Institute of Chicago (Abrams, 1970), p. 87 (ill.).

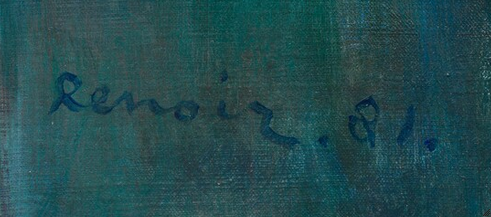

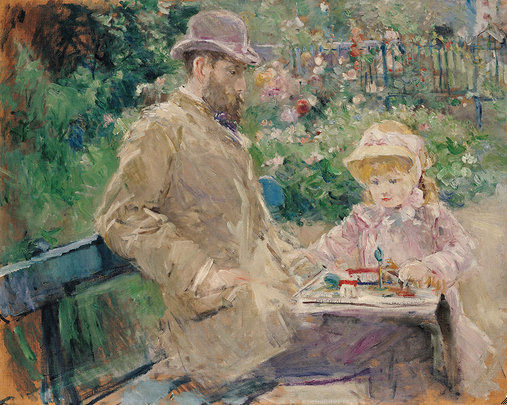

François Daulte, Auguste Renoir: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, vol. 1, Figures, 1860–1890 (Durand-Ruel, 1971), pp. 268–69, cat. 378 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Summer Gallery Talks,” Calendar of the Art Institute of Chicago 65, 3 (May–Aug. 1971), p. 18.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Exhibition Schedule,” Calendar of the Art Institute of Chicago 66, 2 (Mar. 1972), p. 7 (ill.).

Elda Fezzi, L’opera completa di Renoir: Nel periodo impressionista, 1869–1883, Classici dell’arte 59 (Rizzoli, 1972), p. 109, cat. 471 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Lecturer’s Choice,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 67, 4 (Jul.–Aug. 1973), p. 11.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 26; 96–97, cat. 34 (ill.); 210–11; 212; 213 (ill.); 214.

John Rewald, “Jours sombres de l’impressionnisme, Paul Durand-Ruel et l’expostition des impessionnistes, à Londres, en 1905,” L’oeil 223 (Feb. 1974), pp. 15 (ill.), 18.

Art Institute of Chicago, 100 Masterpieces (Art Institute of Chicago, 1978), pp. 102–03, pl. 58.

Patricia Erens, Masterpieces: Famous Chicagoans and Their Paintings (Chicago Review, 1979), p. 57.

J. Patrice Marandel, The Art Institute of Chicago: Favorite Impressionist Paintings (Crown, 1979), front cover (detail), p. 106.

Sophie Monneret, L’impressionnisme et son époque: Dictionnaire international illustré, vol. 2 (Denoël, 1979), pp. 172, 175.

Joel Isaacson, The Crisis of Impressionism, 1878–1882, exh. cat. (University of Michigan Museum of Art, 1980), p. 32.

Diane Kelder, The Great Book of French Impressionism (Abbeville, 1980), pp. 260 (ill.), 261 (detail), 438.

Diane Kelder, The Great Book of French Impressionism, Tiny Folios (Abbeville, 1980), back cover (ill.); p. 161, pl. 20.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Special Programs,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 75, 1 (Jan.–Mar. 1981), p. 19.

Gerd Betz, Auguste Renoir: Leben und Werk (Belser, 1982), pp. 44, 51 (ill.).

Barbara Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters (Abrams, 1984), pp. 104–05 (ill.), 106.

Art Institute of Chicago, Seibu Museum of Art, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, and Fukuoka Art Museum, eds. Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The Impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], trans. Akihiko Inoue, Hideo Namba, Heisaku Harada, and Yoko Maeda, exh. cat. (Nippon Television Network, 1985), front cover (ill.); pp. 18 (ill.); 81, cat. 35 (ill.); 146; 147, cat. 35 (ill.).

Joel Isaacson, “The Painters Called Impressionists,” in The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, ed. Charles S. Moffett, with Ruth Berson, Barbara Lee Williams, and Fronia E. Wissman, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), pp. 387, 394, 395.

Richard R. Brettell, French Impressionists (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1987), pp. 55, 70 (ill.), 71, 119.

Ministry of Culture; State Hermitage Museum; Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and Art Institute of Chicago, Ot Delakrua do Matissa: Shedevry frantsuzskoi zhivopisi XIX–nachala XX veka, iz Muzeia Metropoliten v N’iu-Iorke i Khudozhestvennogo Instituta v Chikago [From Delacroix to Matisse: Masterpieces of French painting of the nineteenth to the beginning of the twentieth century from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago], trans. from English by Iu. A. Kleiner and A. A. Zhukov, exh. cat. (Avrora, 1988), p. 64.

Sophie Monneret, Renoir, Profils de l’art (Chêne, 1989), p. 153, fig. 15.

Rachel Barnes, ed., Renoir by Renoir, Artists by Themselves (Webb & Bower, 1990), pp. 40–41 (ill.). Translated into Japanese by Reiko Kokatsu as Runowaru (Renoir), Nikkei Pocket Gallery (Nihon Keizai, 1991), pp. 46–47 (ill), 87.

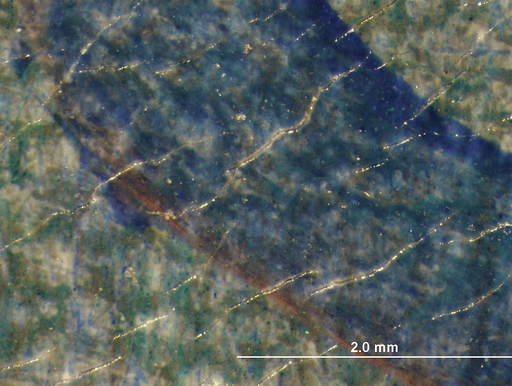

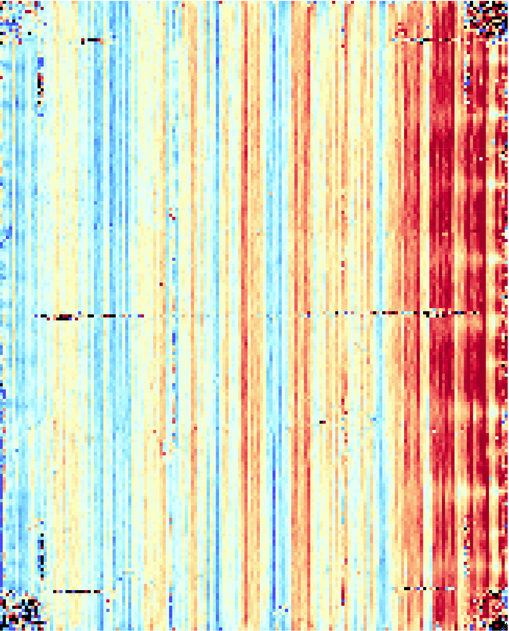

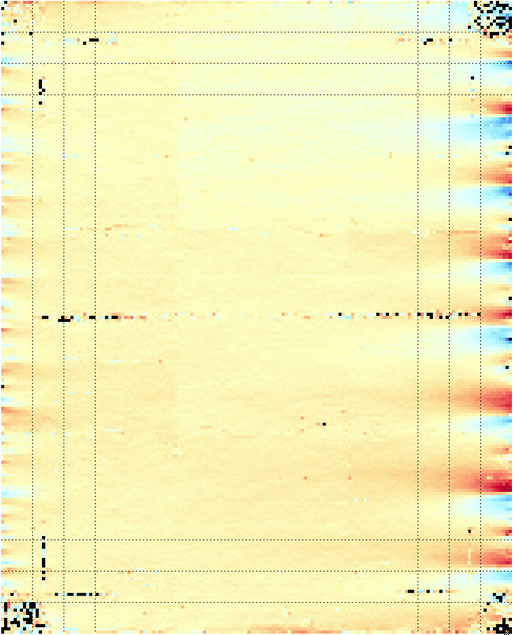

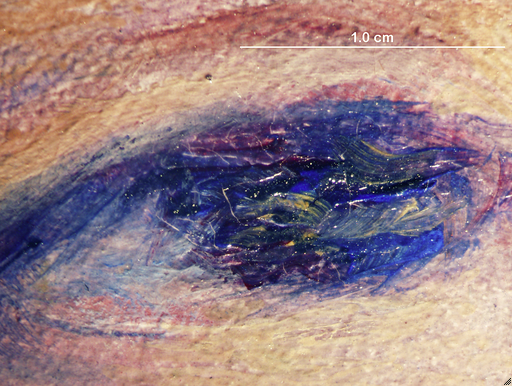

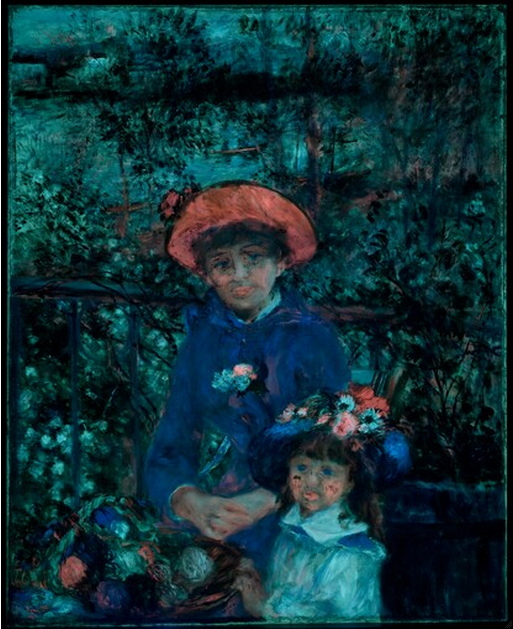

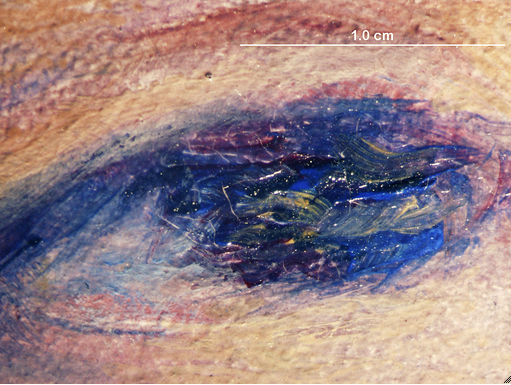

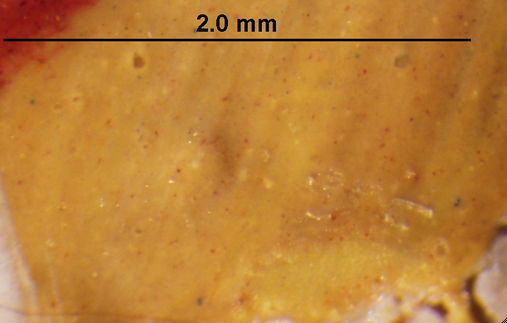

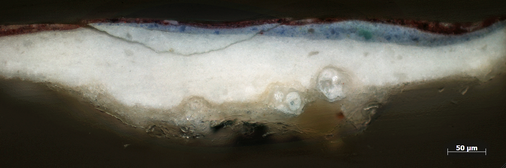

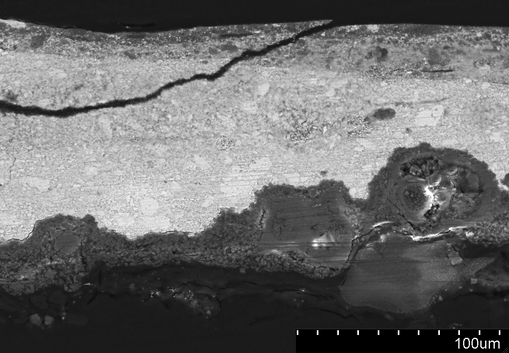

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/Yale University Press, 1990), pp. 190; 191, pl. 200.

Lesley Stevenson, Renoir (Bison Group, 1991), pp. 106–07 (ill.), 109.

Martha Kapos, ed., The Impressionists: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin/Macmillan, 1991), p. 234, pl. 74.

Anne Distel, Renoir: “Il faut embellir” (Gallimard/Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1993), pp. 77 (ill. and details), 169. Translated as Renoir: A Sensuous Vision (Thames & Hudson, 1995), pp. 77 (ill. and details), 169.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), p. 87 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago: The Essential Guide, selected by James N. Wood and Teri J. Edelstein, entries written and compiled by Sally Ruth May (Art Institute of Chicago, 1993), p. 157 (ill.).

Gerhard Gruitrooy, Renoir: A Master of Impressionism (Todtri, 1994), pp. 49, 70 (ill).

Christie’s, New York, Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture (Part I), sales cat. (Christie’s, New York, May 11, 1995), p. 38, fig. 1.

Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 377, 386, 395, 396, 400, 417.

Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 2, Exhibited Works (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 210, 229 (ill.).

Francesca Castellani, Pierre-Auguste Renoir: La vita e l’opera (Mondadori, 1996), pp. 138, 149 (ill.).

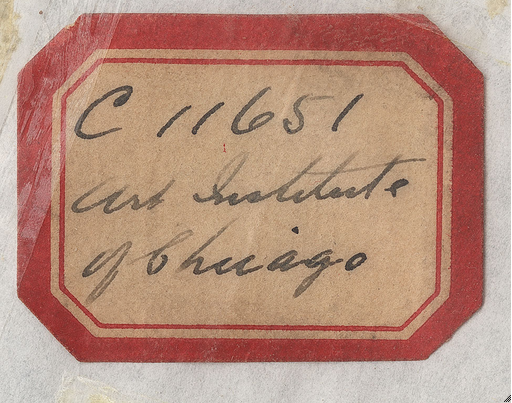

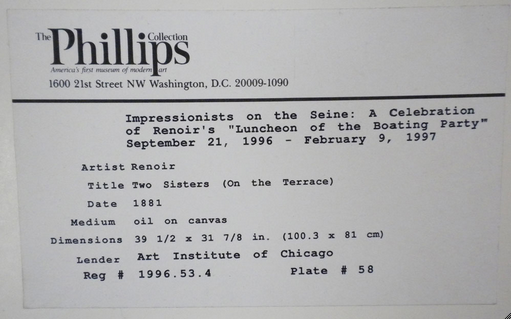

Eliza E. Rathbone, “Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party: Tradition and the New,” in Eliza E. Rathbone, Katherine Rothkopf, Richard R. Brettell, and Charles S. Moffett, Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” exh. cat. (Phillips Collection/Counterpoint, 1996), p. 49.

Eliza E. Rathbone, Katherine Rothkopf, Richard R. Brettell, and Charles S. Moffett, Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” exh. cat. (Phillips Collection/Counterpoint, 1996), pp. 216, pl. 58; 259.

Katherine Rothkopf, “From Argenteuil to Bougival: Life and Leisure on the Seine, 1868–1882,” in Eliza E. Rathbone, Katherine Rothkopf, Richard R. Brettell, and Charles S. Moffett, Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” exh. cat. (Phillips Collection/Counterpoint, 1996), p. 64.

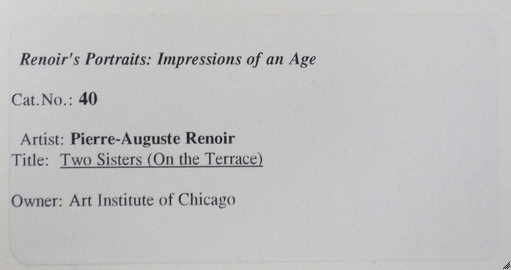

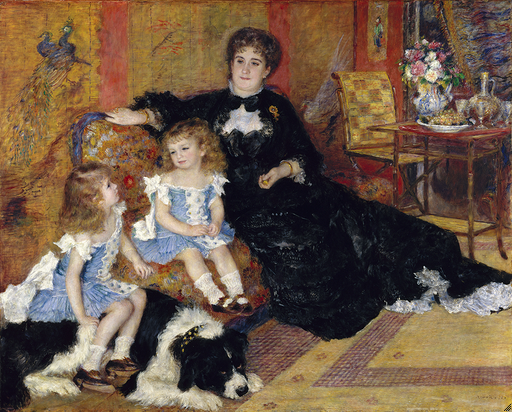

Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 175; 186–189, cat. 40 (ill.); 301, n. 14; 308–10, cat. 40. Translated by Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, with support from Nada Kerpan for the texts by Linda Nochlin, as Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), pp. 175; 186–89, cat. 40 (ill.); 301, n. 14; 308–10, cat. 40.

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), front cover (ill.); pp. 6; 43 (detail); 49; 50–51; 54–55; 72; 80; 93, pl. 12; 110.

Sophie Monneret, Sur le pas de impressionnistes (Éd. de la Martinière, 1997), p. 96.

Charles Moffett, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Young Women at the Water’s Edge,” in The Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, Impressionists and Modern Masters, ed. Libby Lumpkin, exh. cat. (Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, Mirage Resorts, 1998), pp. 47, 50 (ill.).

Kimbell Art Museum, “Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age,” Calendar (Aug. 1997–Jan. 1998), p. 14 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Master Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 1999), p. 59 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Shikago bijutsukan [The Art Institute of Chicago], Museums of the World 22 (Kodansha, 2000), p. 20 (ill.).

Barbara Dayer Gallati, William Merritt Chase: Modern American Space, 1886–1890, exh. cat. (Brooklyn Museum of Art/Abrams, 2000), pp. 42; 43, fig. 11.

Belinda Thomson, Impressionism: Origins, Practice, Reception (Thames & Hudson, 2000), p. 206, ill. 207; 207; 268.

Paul Joannides, Renoir: Sa vie, son oeuvre (Soline, 2000), pp. 1 (detail), 90–91 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), front cover (ill.); pp. 9, 10, 71 (ill.), 76.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures from the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood, commentaries by Debra N. Mancoff (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), back cover (ill.); pp. 183, 206 (ill.).

Gilles Néret, Renoir: Painter of Happiness, 1841–1919, trans. Josephine Bacon (Taschen, 2001), pp. 2 (ill.), 440.

Simona Barrolena, Impressionismo (Mondadori Electa, 2002), p. 168 (ill.).

Sculpture Foundation, Solid Impressions: J. Seward Johnson, Jr. (Sculpture Foundation, 2002), pp. 60 (ill.), 70.

Philippe Cros, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (Terrail, 2003), pp. 84, 88–89 (ill.).

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Beyond the Frame: Impressionism Revisited; The Sculptures of J. Seward Johnson, Jr., with an essay by Petra Ten-Doesschate Chu (Bulfinch, 2003), p. 121 (ill.).

Norio Shimada, Inshoha bijutsukan [History of impressionism] (Shogakukan, 2004), p. 436 (ill.).

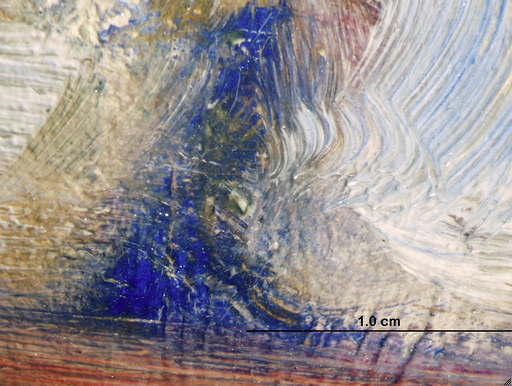

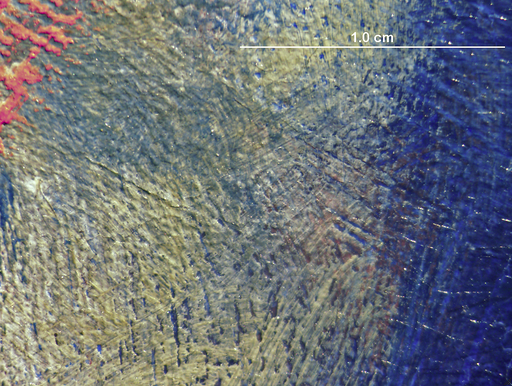

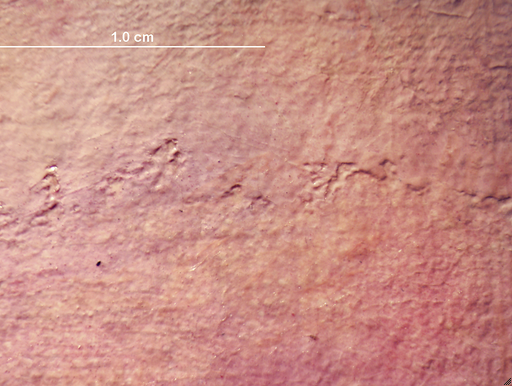

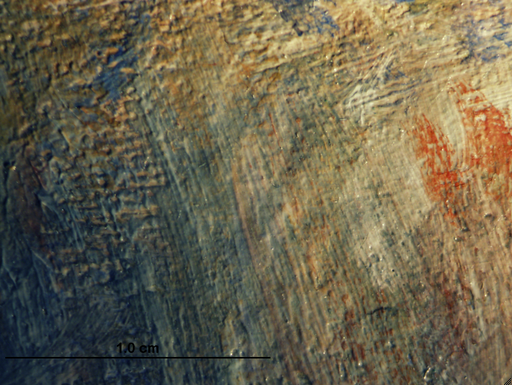

Aviva Burnstock, Klaas Jan van den Berg, and John House, “Painting Techniques of Pierre-Auguste Renoir: 1868–1919,” Art Matters: Netherlandish Technical Studies in Art 3 (2005), p. 52.

Kyoko Kagawa, Runowaru [Pierre-Auguste Renoir], Seiyo kaiga no kyosho [Great Masters of Western Art] 4 (Shogakukan, 2006), p. 58 (ill.).

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art/University of Washington Press, 2007), pp. 97; 98, fig. 33.

Colin B. Bailey, “Rowers at Chatou, 1880–1,” in Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), pp. 212, fig. 102; 214. Translated by Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer as Colin B. Bailey, “Les canotiers à Chatou, 1880–1881,” in Les paysages de Renoir 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle), exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), pp. 212, fig. 102; 214.

Colin B. Bailey, “‘The Greatest Luminosity, Colour and Harmony’: Renoir’s Landscapes, 1862–1883,” in Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), pp. 65, 70. Translated as Colin B. Bailey, “‘Un maximum de luminosité; de coloration, et d’harmonie’: Les paysages de Renoir, 1862–1883,” in Les paysages de Renoir 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, trans. Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), pp. 65, 70.

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, with the collaboration of Camille Frémontier-Murphy, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, vol. 1, 1858–1881 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2007), pp. 299–300, cat. 254 (ill.).

Peter Kropmanns, “Renoir und der Impressionismus,” in Auguste Renoir und die Landschaft des Impressionismus, ed. Gerhard Finckh, exh. cat. (Von der Heydt-Museum, 2007), pp. 74–75 (ill.).

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 10 (detail); 24 (ill.); 74–75, cat. 28 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 10 (detail); 24 (ill.); 74–75, cat. 28 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, The Essential Guide (Art Institute of Chicago, 2009), p. 218 (ill.).

Anne Distel, Renoir (Citadelles & Mazenod, 2009), pp. 194; 195, ill. 181; 239.

Art Institute of Chicago, Master Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James Cuno (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2009), p. 59 (ill.).

Adrien Goetz, Comment Regarder . . . Renoir (Hazan, 2009), p. 135 (ill.).

Marie-Christine Decrooq, “Monet und Durand-Ruel: Die Finanzkrise und die 7. Impressionisten-Ausstellung im Licht ihrer Korrespondenz (Januar bis März 1882) aus dem Archiv Cornebois,” in Claude Monet, ed. Gerhard Finckh, exh. cat. (von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal, 2009), p. 59 (ill.).

Sylvie Patry, “Renoir, Revolutionary and Classical,” in Sounjou Seo, Renoir: Promise of Happiness, exh. cat. (Seoul Museum of Art, 2009), p. 30, fig. 7.

Caroline Durand-Ruel Godfroy, “Paul Durand-Ruel and Renoir: 47 Years of Friendship,” in Sounjou Seo, Renoir: Promise of Happiness, exh. cat. (Seoul Museum of Art, 2009), pp. 158; 161; 166, n. 13; 167, n. 47; 275; 276; 279, n. 13 and n. 47.

Greg M. Thomas, Impressionist Children: Childhood, Family, and Modern Identity in French Art (Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 50; 51, fig. 56.

Caroline Homes, Impressionists in Their Garden (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2012), pp. 132–33 (ill.).

Debra N. Mancoff, Fashion in Impressionist Paris (Merrell, 2012), pp. 138–39 (ill.), 149.

Bernhard Echte and Walter Feilchenfeldt, eds., with assistance by Petra Cordioli, Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer: Die Ausstellungen 1905–1908 (Nimbus. Kunst und Bücher, 2013), pp. 208 (ill.), 213, 803.