Cat. 46

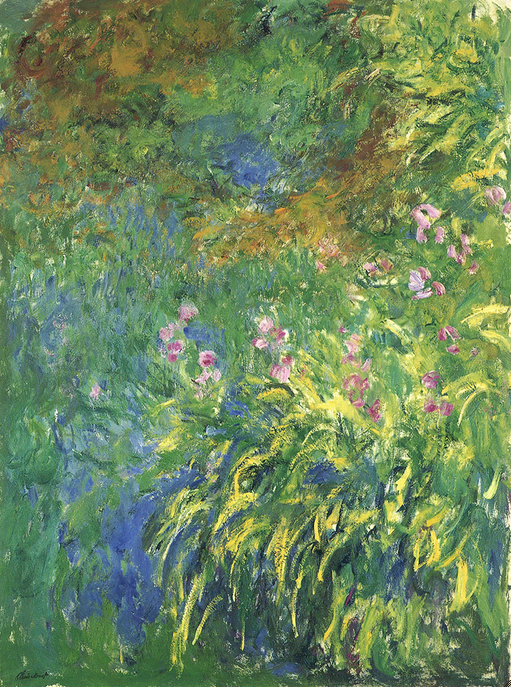

Irises

1914/17

Oil on canvas; 200 × 200.7 cm (78 3/4 × 79 in.)

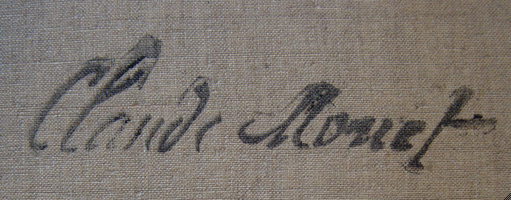

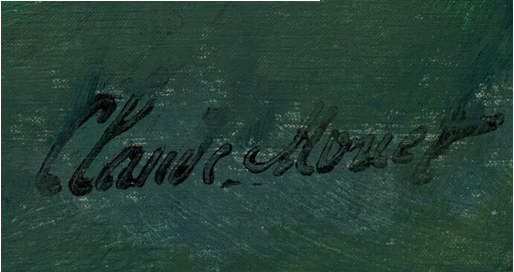

Stamped: Claude Monet (lower right, in black paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Art Institute Purchase Fund, 1956.1202

Decorations Revisited

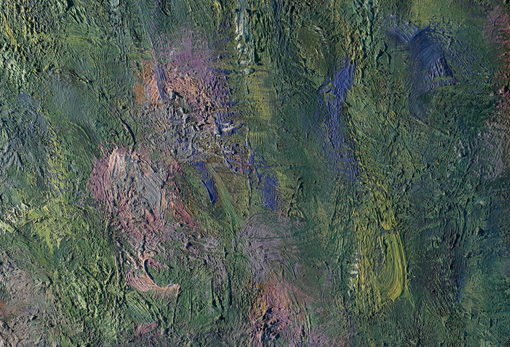

Irises is an example of the artistic experiments Claude Monet undertook during World War I. It treats a familiar subject—the plantings surrounding his water lily pond—that he had focused on intensively since 1899 (see cat. 37). But, measuring approximately 6 1/2 feet square, Irises literally and figuratively expands the scale of his beloved water garden, a treatment representative of the artist’s late oeuvre. Irises was part of a group that Monet created on the heels of a period of relative inactivity after the exhibition of his Venice pictures at Bernheim-Jeune in May–June 1912 (see cat. 45). Undoubtedly Monet’s artistic stagnation was caused by the deaths of his second wife, Alice, in May 1911, and his son Jean in February 1914, as well as the discovery that he had cataracts. But by April 30 of that year, Monet showed signs of rejuvenation, describing to his friend Gustave Geffroy, “I am even planning to embark on some big paintings, for which I found some old attempts in a basement. Clemenceau saw them and was amazed. Anyway, you’ll see something of this soon, I hope.” By late May or early June 1914, Monet had reinvigorated his artistic practice.

The project to which Monet referred was one that he had spoken about as early as August 1897 to writer Maurice Guillemot, who was in Giverny to visit and interview the artist, then at work on the Mornings on the Seine series (see cat. 36). Recalling his chat with Monet, part of which took place under the parasol on the bank of the pond, Guillemot referred to a decorative project, an interior environment comprised of mural-like paintings, that was percolating in the artist’s mind: “The oasis [Monet’s water lily pond] is [the most] charming of all the models he decided on; for these are the models for a decoration, for which he has already begun to paint studies, large panels, which he showed me afterward in his studio. Imagine a circular room in which the dado beneath the molding is covered with [paintings of] water, dotted with these plants to the very horizon, walls of a transparency alternately green and mauve, the calm and silence of the still waters reflecting the opened blossoms. The tones are vague, deliciously nuanced, with a dreamlike delicacy.”

The Experience of War

The realities of the war did not deter Monet’s work on this new project. He was determined to remain in Giverny, despite the fact that most of his family and many of the locals in the village evacuated. Monet demonstrated his usual tenacity, as expressed in a letter to his friend the art critic Gustave Geffroy in early September 1914: “As for me, I will stay here all the same, and if these savages must kill me, it will be in the midst of my canvases, in front of all of my life’s work.” By early January 1915, he had described the undertaking as his Grande decoration, “a project that I have been involved with for some time already; water, water lilies, plants, but on a very large scale.”

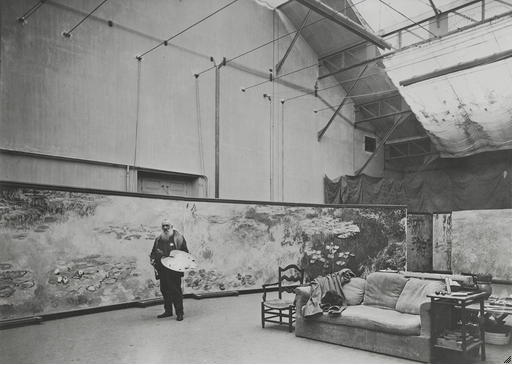

Indeed, these paintings were so large that Monet found it necessary to build a third studio, 276 square meters in size and complete with skylights, to accommodate the bigger canvases (fig. 46.1). The true intention of many of the panels is unclear. Some were probably not conceived as decorations in their own right. Rather, they were likely studies transported from the bank of Monet’s water lily pond to his new studio, where panels could be placed side by side to build up the three-, four-, and five-meter paintings that the artist would ultimately offer to the French nation. Others were probably destined for the decorative project, but ultimately some made it in, and some did not. Monet intended this gift to be a patriotic gesture, as he explained to the recently appointed prime minister, Georges Clemenceau (previously minister of war), on November 12, 1918: “I am on the verge of finishing 2 decorative panels that I want to sign on the day of the Victory, and I am going to ask you to offer them to the State . . . It’s not much, but it is the only way I have of taking part in the victory.” Although the terms of Monet’s donation would be fraught with complications, it led to the eventual installation of the Water Lily Pond murals in Paris’s Musée de l’Orangerie (fig. 46.2).

Constructing Irises

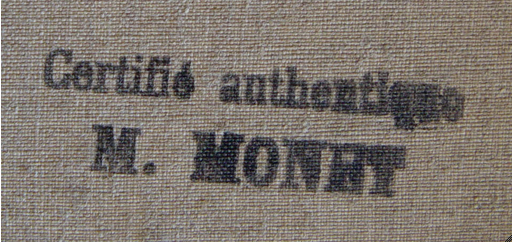

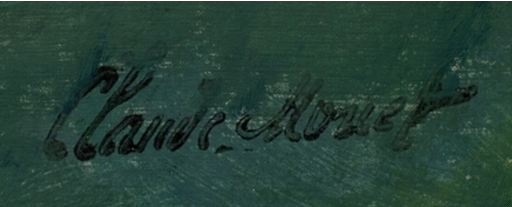

Although the function of Irises is ambiguous—it is radically different from any passage included in the final mural cycle—it was certainly not created for exhibition or sale. The painting was never signed or dated, suggesting that the artist did not consider it a “finished” work that he would have exhibited or sold. Irises does bear a signature stamp, which does not quite mimic Monet’s actual autograph on the front of the canvas (fig. 46.3), as well as two additional estate stamps on the back, probably applied well after Monet’s death by his son Michel, who inherited the studio. Likely because these late paintings looked so different from what the public expected of the artist’s work, Michel—probably in conjunction with Paris dealer Katia Granoff, who sold many of Monet’s late works—devised a set of stamps to guarantee the authenticity of the paintings that were leaving the deceased artist’s studio.

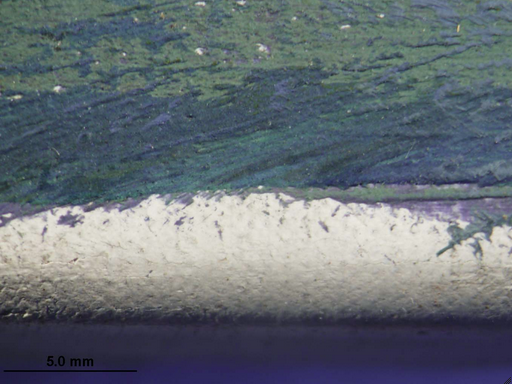

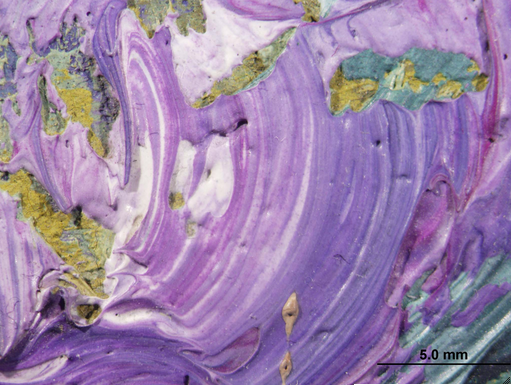

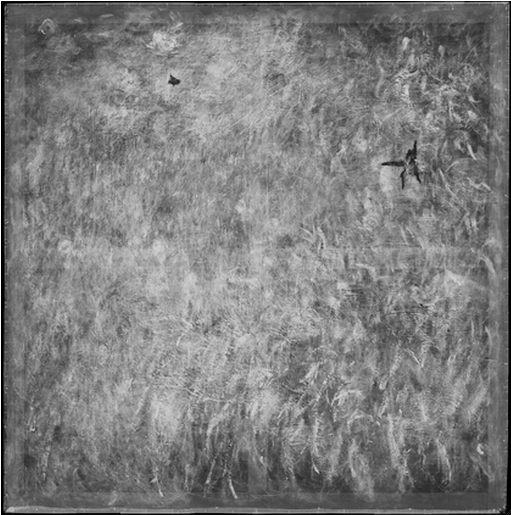

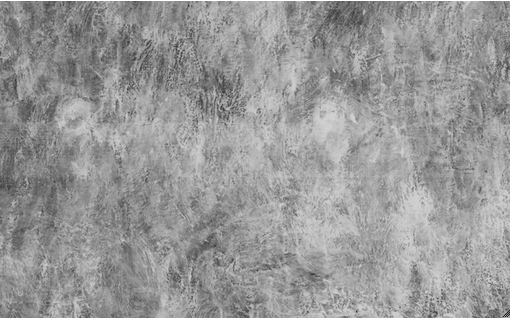

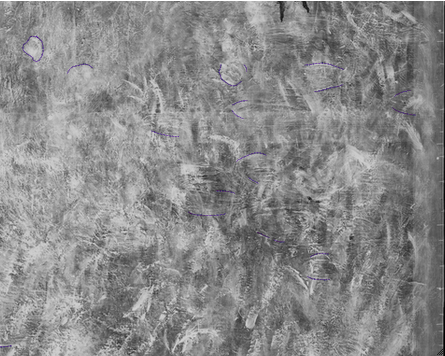

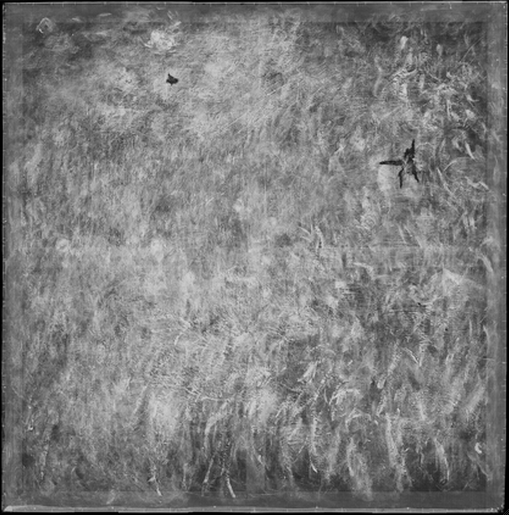

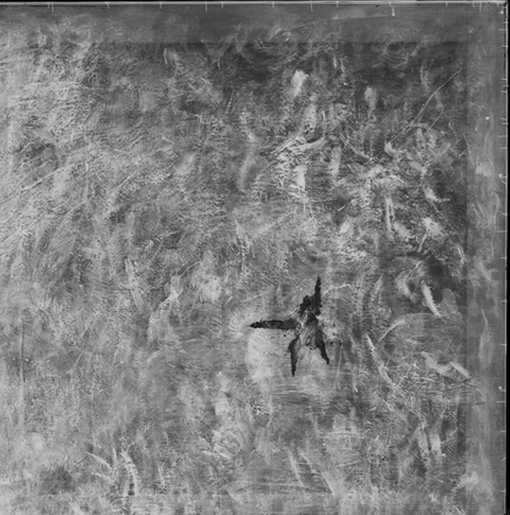

The fact that Irises was unfinished does not mean that Monet carried it out quickly or without sustained effort. Technical examination shows that the painting—executed on a pre-primed, very fine canvas—was very thickly worked up in multiple layers of wet-over-dry paint, which suggests multiple sessions over a significant period of time (fig. 46.4; see Technical Report). X-ray and transmitted-infrared images also show that Monet may have made compositional changes to the canvas: it appears that earlier water lilies may have been painted out, indicating that the work began as a study that was focused more on the pond than on the plantings that surrounded it (fig. 46.5; see Technical Report). That Monet produced a handful of other paintings related to Irises, including The Path through the Irises (fig. 46.6 [W1828]), Irises (fig. 46.7 [W1829]), and Irises by the Pond (fig. 46.8 [W1832]), also reflects his commitment to perfecting the composition of this motif. Technical analysis of the version in the National Gallery, London, indicates that Monet also carried out this work in several sessions, for the thickest impasto on the surface was applied over a layer of partially dried paint.

Acquiring Irises

Although the Art Institute of Chicago had been given numerous Monet works, Irises was the first Monet painting that was purchased by the museum. In 1956 Katharine Kuh, the Art Institute’s pioneering curator of modern art, must have perceived the acquisition of the work as potentially risky, as she wrote to her mother about her recent purchase: “Edgar Kauffman [son of the Pennsylvania businessman who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater] . . . gave me courage to buy for the museum a fine very late very free very large Monet of water lilies and iris. Quite marvelous! and of course not cheap!” Kuh’s tentativeness was certainly a result of the reception of Monet’s late paintings, which was initially lukewarm at best, but that was undergoing a major reconsideration. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, private collectors began acquiring some of the works, but it was the purchase of one of Monet’s mural sized compositions in 1955 by New York’s Museum of Modern Art that precipitated American excitement for them. Kuh’s purchase of Irises followed that of the Museum of Modern Art, but it was trailblazing among other American institutions. The Art Institute’s purchase of Irises preceded the first exhibition in the United States to feature the late paintings (at Knoedler & Company in New York in fall 1956) as well as the sale of a large triptych that was divided and sold by Knoedler to the Saint Louis Art Museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

The purchase of Irises surely instigated the organization of a Monet exhibition at the Art Institute the following year. The press release for the show not only billed Irises as the crown jewel that rounded out museum’s Monet holdings but also presented the work as a survivor and living witness to the ravages of World War II: “During the Second World War, the whole lot of these forgotten canvases [like Irises] almost perished. The Germans attacked the storage where they were hidden and unknowingly riddled some of them with machine-gun bullets.” This account may explain the localized damage that the painting had suffered before it entered the Art Institute’s collection (see Technical Report). Monet’s stepson, Jean-Pierre Hoschedé, reported that some of Monet’s canvases were damaged by shrapnel from shells during the war, and it has been recorded that a number of the other late works suffered the same fate.

Jill Shaw

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Claude Monet’s Irises was painted on a pre-primed, non-standard-size (square), linen canvas. The work is in its original unlined and unvarnished state. The ground is off-white and appears to consist of two layers. The work is densely built up on a very fine canvas using thick, textural brushstrokes. The final surface of the work relies heavily on the texture and color of multiple, superimposed layers of brushwork. Earlier brushstrokes whose texture remains visible on the surface of the painting in the form of oval shapes, are suggestive of water lilies that may have been included in an earlier painting stage and then painted out. Similarly, a few of the irises were painted over, leaving traces of the purple paint visible through breaks in the brushwork. Overall, the paint has a dry, matte appearance, with localized areas of glossier paint. The work is unsigned but has an estate signature stamp in the lower right corner. Another signature stamp was applied to the back of the canvas in the upper right corner, along with an authentication stamp. Some of the brushwork in the lower right corner passes over the stamp, indicating that some reworking of the corners and edges of the painting was probably carried out after the artist’s death.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 46.9).

Signature

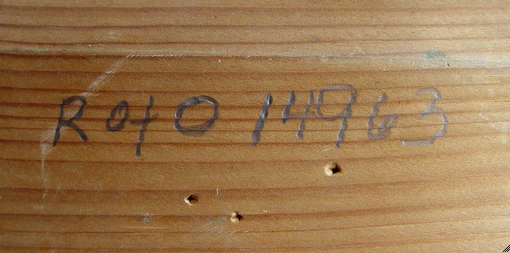

Stamped: Claude Monet (lower right, in black paint) (fig. 46.10). The underlying paint was dry when the stamp was applied. In addition, there are two stamps on the back of the canvas: Claude Monet (upper right, in black paint or ink) (fig. 46.11); and Certifié authentique / M. MONET (upper right, in black paint or ink) (fig. 46.12).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The canvas is not a standard size. It was probably custom ordered and cut from a roll of preprimed canvas along the top and bottom edges, with the left and right edges corresponding closely to the original width of the canvas roll, which probably would have been slightly wider than the current 208.4 cm width of the canvas (including the tacking margins) (see Ground Application).

Weave

Plain weave. Average thread count (standard deviation): 26.4V (0.4) × 25.5H (1.1) threads/cm; the vertical threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the horizontal threads to the weft. No thread count or weave matches were found with other Monet paintings analyzed for this project.

Canvas characteristics

There is moderate cusping on the left and right edges, and mild cusping on the top and bottom edges.

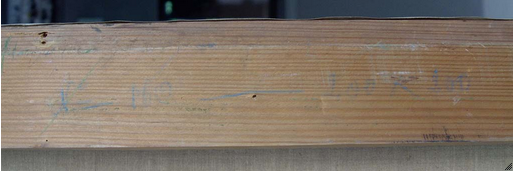

Stretching

Current stretching: The work appears to retain its original stretching. Tack spacing ranges from approximately 2.5–14.0 cm apart. The canvas has deteriorated around many of the original tacks and additional copper tacks have been added as reinforcements. Empty holes on the tacking edges that continue into the stretcher are from nails used to attach the previous wooden strip frame that was removed in 2013 (see Frame History). Cusping appears to correspond to the placement of the original tacks (fig. 46.13).

Original stretching: See above.

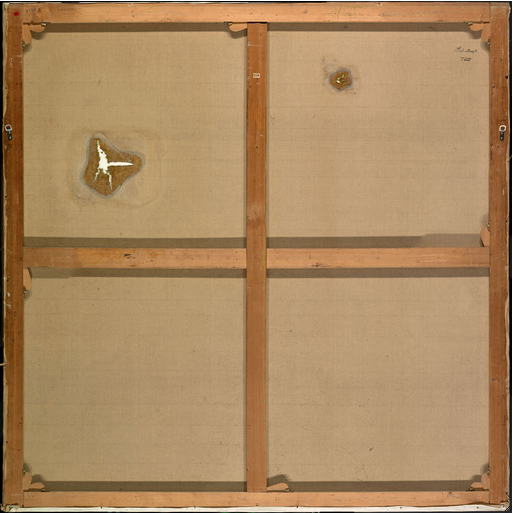

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: The painting retains its original stretcher (fig. 46.14). It is a six-membered, beveled, wooden stretcher with a horizontal and a vertical crossbar, and mortise and half-miter joints with twelve keys. Overall dimensions: 200.0 × 200.7 cm; stretcher-bar width: 7.9 cm; inner stretcher-bar depth: 2.0 cm; outer stretcher-bar depth: 2.3 cm; crossbar width: 7.9 cm; crossbar depth: 2.0 cm.

Original stretcher: See above.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

The ground extends to the top and bottom edges of the canvas, indicating that the canvas was cut from a longer piece of primed fabric on those sides. The ground stops short of the left and right edges, where there is approximately 2 cm of unprimed canvas on each side. The current width of the canvas is probably very close to the width of the roll from which it was cut, and the unprimed edges probably correspond to the edges of the original canvas roll that were attached to the priming frame. On the left and right sides, there is often a thick ridge of ground that probably relates to the application. The texture of the canvas remains visible, but because the weave is so fine, the surface has a relatively smooth appearance. On the tacking edges, the surface of the ground appears brushmarked. On the painting surface, several ridges and lines suggestive of the use of a palette knife are visible but it is unclear whether these marks are in the ground layer or early paint layers (see Application/technique) (fig. 46.15).

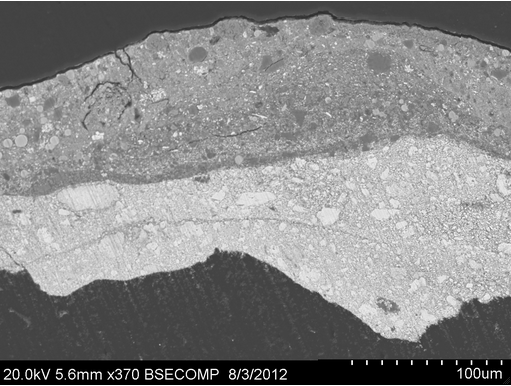

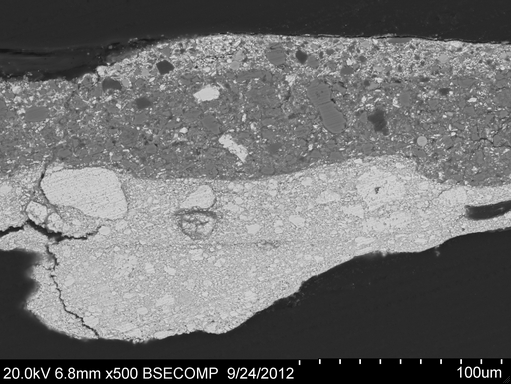

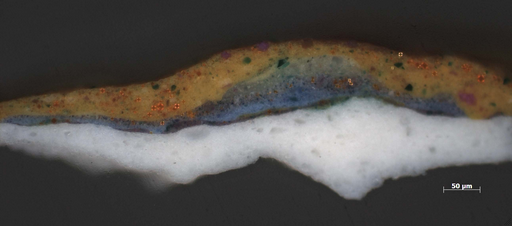

A cross section of the ground and canvas layers from the bottom tacking edge indicates that the ground consists of a single layer (fig. 46.16) (fig. 46.17). The thickness of the layer ranges from approximately 20 to 120 µm. Backscattered electron (BSE) images of two additional samples taken from the picture plane, however, show a clear demarcation that indicates two distinct ground layers (fig. 46.18, fig. 46.19). In each of these samples, the overall thickness of the ground ranges from approximately 20 to 80 µm and 50 to 140 µm, respectively. It is difficult to say definitively whether these results indicate that an additional ground layer was applied only to the picture plane (i.e., after the canvas was stretched) or whether the cross sections from within the painted area capture overlapping brushstrokes of a single application.

Color

Off-white (fig. 46.20).

Materials/composition

Analysis indicates that the ground contains lead white with traces of iron oxide, alumina, silica, calcium-based white, and silicates. In the cross sections from the picture plane that indicated two distinct layers, the composition in the upper and the lower layers was found to be similar. Binder: Oil (estimated).

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No underdrawing was observed with infrared reflectography (IRR) or microscopic examination.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

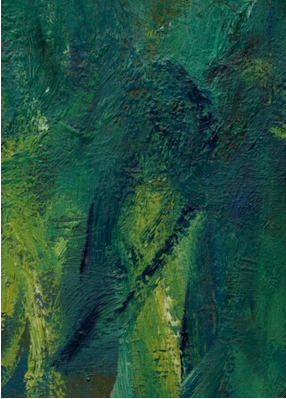

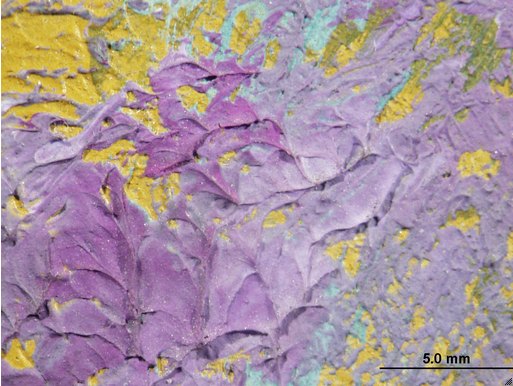

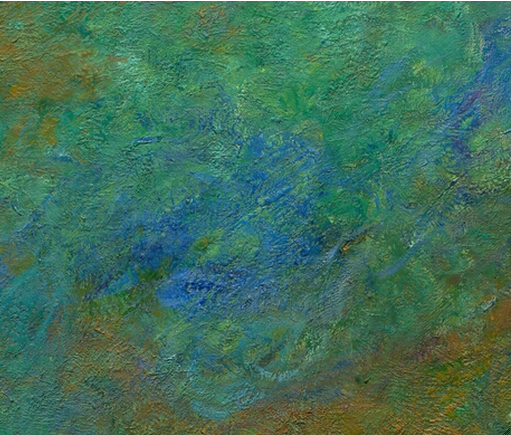

The painting was very thickly built up in layers of superimposed brushstrokes. The highly textured surface is evident when the painting is viewed in raking light (fig. 46.21). The X-ray further reveals the dense mass of brushwork that covers most of the canvas (fig. 46.22). The work is much more thinly painted at the edges and the corners where the ground layer remains visible through the thin applications of paint (fig. 46.23, fig. 46.24). Some of this paint from the periphery is associated with the initial lay-in of the composition. It consists of very thin washes of opaque color that present a flat, matte surface. The paint appears to have been thinned with solvent. Where the brush was lightly dragged, the texture of the canvas weave is evident. The artist then began building up low-relief texture that was ultimately covered by subsequent brushwork (fig. 46.25). In some of the earlier paint layers, it seems that the artist used a palette knife, or similar straight, rigid implement, to apply the paint. The tool marks are visible throughout the X-ray, and the texture of the ridges created by the application technique remains visible on the surface of the painting (fig. 46.26). Compositional elements, such as the slender leaves and the flowers of the irises, were articulated with thick strokes of impasto (fig. 46.27, fig. 46.28). In other areas, such as the patches of orange in the upper part of the composition, the brush was lightly dragged across the surface, accentuating the rough texture of the layers underneath (fig. 46.29).

Where the brushwork is very densely worked up, it is difficult to trace the progression of the painting process. Underlying brushstrokes often seem unrelated to specific forms in the final composition but are not necessarily the result of actual pentimenti. In fact, it seems that much of the underlying brushwork was designed to build up a network of color and texture that contributes in various ways to the final appearance of the painting. This is evident, for example, in the way that colors from earlier paint layers show through small breaks in the brushwork applied on top (fig. 46.30, fig. 46.31), and the way that the texture of underlying brushmarks remains evident even when covered by subsequent layers of paint (fig. 46.32). Texture from the earlier layers is actually emphasized in places by Monet’s technique of applying fairly thin, light-handed strokes that graze the peaks of the already dry brush ridges and impasto underneath, creating a corrugated texture (fig. 46.33). The fact that the painting was carried out with multiple layers of wet-over-dry paint application, including some thick, textural underlayers, suggests that the work was executed in several sessions over a significant period of time.

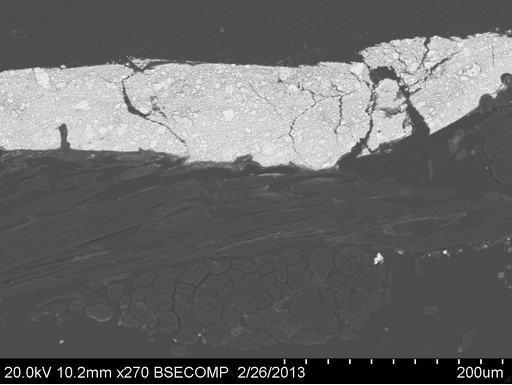

The work shows some evidence of compositional changes. In the midright section of the painting, there are several underlying brushstrokes that form ovoid shapes. These are visible in the X-ray and transmitted-infrared images and are suggestive of water lily plants (fig. 46.34). These painted-out forms may indicate that an earlier painting stage focused more on the water-lily pond than on the irises. Monet also appears to have painted out some of the flowers from the final composition. This is visible in a few areas of dense, relatively radio-opaque brushwork that appear similar in the X-ray to the way in which the flowers visible on the surface were constructed (fig. 46.35). In a couple of places, where the underlying paint layers are exposed, the purple hue of the irises is visible (fig. 46.36). Several additional, similarly dense strokes are visible in other parts of the X-ray but are not apparent in the final composition, suggesting that other flowers may have been included initially but were subsequently painted over (fig. 46.37).

As mentioned above, some thin paint layers were applied to the edges and corners of the canvas in the early painting stages. Other brushwork, however, was clearly added to these areas at a later time. The dull-green paint that was applied around the signature stamp, for example, overlaps the stamp slightly (fig. 46.38), indicating that this paint was applied after the estate stamp and, therefore, by someone other than the artist. UV examination shows that the later, dull-green paint in the lower right corner was applied around the signature stamp but overlaps it in places at the top of the stamp (fig. 46.39). Two significant damages to the painting, which seem like accidental punctures or impacts that resulted in tears in the canvas (see Condition Summary), were documented upon arrival of the work at the Art Institute in 1956 and may have occurred while the work was in the artist’s studio.

Painting tools

Brushes, including 1–3 cm width (based on width of brushstrokes), as well as a rigid tool, such as a palette knife, used for earlier paint layers.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, cadmium yellow, zinc yellow, red lake (madder), viridian, cobalt blue, ultramarine blue, and cobalt violet; SEM/EDX analysis also detected the possible presence of chrome yellow. UV fluorescence of several deep-red brushstrokes indicates the use of red lake for the iris leaves (fig. 46.40). The complexity of Monet's layering and paint mixtures is illustrated by a cross section taken from an orange area near the upper left corner of the painting. Also visible in the cross section are small spherical particles of cadmium orange (fig. 46.41).

Binding media

Oil (estimated). In general, the paint has a notably dry, matte surface appearance.

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting retains its original, unvarnished surface. The paint has a dry, matte appearance with localized strokes of glossy, more medium-rich paint.

Conservation History

Prior to the acquisition of the painting in 1956, two significant tears in the canvas had been repaired with pieces of gauze adhered to the back of the canvas with a wax-based adhesive. Textured fills were applied to the front of the damaged areas, overlapping the edges of the original paint. The damaged areas were repainted.

In 2012–13, the painting was surface cleaned to remove a greasy grime layer. The paint layer was locally consolidated. The two tear areas were treated by removing the old patches and excess wax adhesive from the canvas. The fills and retouching were removed, which exposed well-preserved original paint around the edges of the damage. New patches were applied to the back of the damaged areas and the areas of loss were filled and inpainted. The painting was left unvarnished.

Condition Summary

The painting retains its original unlined and unvarnished state. The work appears to retain its original stretching, although the canvas is deteriorated around many of the original tack holes and additional copper tacks have been added. The canvas is somewhat slack on the stretcher. The unprimed edges of the canvas on the left and right tacking margins are frayed. The painting is very thickly built up and executed on a very fine and fragile canvas. There is a complex tear (spanning approximately 20 × 16 cm, with four branches radiating from a central point of impact) in the upper right quadrant and a smaller tear or puncture (approximately 5 × 4 cm) in the upper left corner. Canvas has been lost in both areas so that the edges of the damage no longer meet and there is associated paint and ground loss around the edges of the damage. Previous repairs to these damaged areas and associated retouching that were thick, brittle, and poorly matched to the original paint were removed in 2012–13. New patches were applied, and the damages were filled and inpainted. There is a repair to the canvas at the lower right corner where the stretcher has created a hole in the fabric. There are several scattered small flake losses (both between the ground and canvas and between paint layers). There are isolated areas of mechanical cracking throughout the paint layer and stretcher-bar cracks over the crossbars. There are some random paint splatters near the bottom edge of the canvas.

Kimberley Muir

Frame

Current frame (2013): The frame is not original to the painting. It is an American, twenty-first-century reproduction of an early-twentieth-century, French, molding frame with a slight cushion profile. It is oil gilded over a black oil paint base. The pine molding is nailed and mitered at the corners (fig. 46.42).

Previous frame (installed 1991; removed 2013): The work was previously housed in a black, painted, wooden, batten-strip frame that exposed the edges of the painting.

Previous frame (installed by 1956; removed 1991): The work was previously housed in an American, mid-twentieth-century, L-shaped, narrow frame with a gilded face (fig. 46.43).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

By descent from the artist (died 1926) to his son, Michel Monet, Giverny.

Acquired by Katia Granoff, Paris, by 1956.

Sold by Katia Granoff, Paris, to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1956.

Selected References

Art Institute of Chicago, “Homage to Claude Monet,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 51, 2 (Apr. 1, 1957), p. 23, 24, 25 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Catalogue,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 51, 2 (Apr. 1, 1957), p. 34.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Exhibitions,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 51, 2 (Apr. 1, 1957), p. 36.

Edith Weigle, “The Wonderful World of Art,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 26, 1957, p. E2.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), pp. 284 (ill.), 322.

A. James Speyer, “Twentieth-Century European Paintings and Sculpture,” Apollo 84, no. 55 (Sept. 1966), p. 222.

Charles C. Cunningham, Instituto de arte de Chicago, El mundo de los museos 2 (Editorial Codex, 1967), pp. 11, ill. 28; 57, no. 4 (ill.).

Jean-Dominique Rey, “Au-delà de la peinture,” in Denis Rouart and Jean-Dominique Rey, Monet, nymphéas, ou Les miroirs du temps, with a cat. rais. by Robert Maillard (Hazan, 1972), pp. 144–45 (ill.).

Denis Rouart and Jean-Dominique Rey, Monet, nymphéas, ou Les miroirs du temps, with a cat. rais. by Robert Maillard (Hazan, 1972), p. 179 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, 100 Masterpieces (Art Institute of Chicago, 1978), p. 94, pl. 51.

A. James Speyer and Courtney Graham Donnell, Twentieth-Century European Paintings (University of Chicago Press, 1980), pp. 12; 60, cat. 3B6; microfiche 3, no. B6 (ill.).

Horst Keller, with a contribution by Herbert Keller, Ein Garten wird Malerei: Monets Jahre in Giverny (DuMont Buchverlag, 1982), pp. 86; 108; 117; 141 (ill.), 159. Translated by Sylvia Gouding as Monet’s Years at Giverny: A Garden Becomes Painting (DuMont Buchverlag/Dumont Monte, 2001), pp. 86, 108, 117, 141 (ill.), 159.

Claire Joyes, Claude Monet: Life at Giverny (Vendome, 1985), p. 107 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 4 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1985), pp. 268; 269, cat. 1833 (ill.).

Andrew Forge, Monet, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), pp. 66; 68; 104, pl. 33; 109.

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue raisonné, vol. 4, Nos. 1596–1983 et les grandes décorations (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), p. 870, cat. 1833 (ill.).

Caroline Holmes, Monet at Giverny (Cassel/Sterling, 2001), pp. 22–23 (ill.).

Norio Shimada and Keiko Sakagami, Kurōdo Mone meigashū: Hikari to kaze no kiseki [Claude Monet: 1881–1926], vol. 2 (Nihon Bijutsu Kyōiku Sentā, 2001), pp. 144, no. 266 (ill.); 191.

Robert Gordon and Sydney Eddison, Monet: The Gardener (Universe, 2002), pp. 55 (ill.), 94.

Katharine Kuh, My Love Affair with Modern Art: Behind the Scenes with a Legendary Curator, ed. Avis Berman (Arcade, 2006), p. 45.

Joseph Baillio, “Katia Granoff (1895–1989): Champion of the Late Works of Claude Monet,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), p. 41.

Eric M. Zafran, “Monet in America,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), pp. 128; 130; 136, fig. 58.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 18 (ill.), 19 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 18 (ill.), 19 (ill.).

Other Documentation

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label

Content: 134 (fig. 46.44)

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: No _ 160 ___ 200 X 200 (fig. 46.45)

Number

Location: right tacking edge

Method: handwritten script

Content: 210 (fig. 46.46)

Pre-1980

Stamp

Location: lower right corner of painting

Method: stamp

Content: Claude Monet (fig. 46.38)

Stamp

Location: canvas

Method: stamp

Content: Claude Monet (fig. 46.11)

Stamp

Location: canvas

Method: stamp

Content: Certifié authentique / M. MONET (fig. 46.12)

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: R of O 14963 (fig. 46.47)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter.

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75H (PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter and B+W UV 010 MRC F-Pro filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis using a Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy

Cross sections analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S3400-N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy

A Jobin Yvon Horiba LabRAM 300 confocal Raman microscope was used, equipped with an Andor multichannel, Peltier-cooled, open-electrode charge-coupled device detector (Andor DV420-OE322; 1024×256), an Olympus BXFM open microscope frame, a holographic notch filter, and a 1,800-grooves/mm dispersive grating. The excitation line of a He-Ne laser (632.8 nm) was focused through a 20× objective onto the samples, and Raman scattering was back collected through the same microscope objective. Power at the samples was kept very low (never exceeding a few mW) by a series of neutral density filters in order to avoid any thermal damage.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

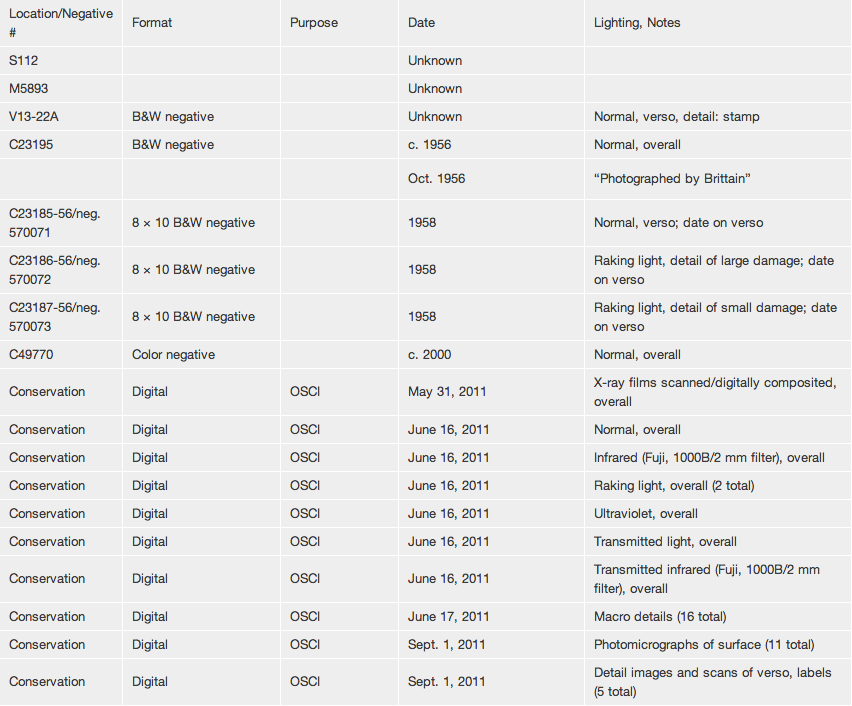

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 46.48).