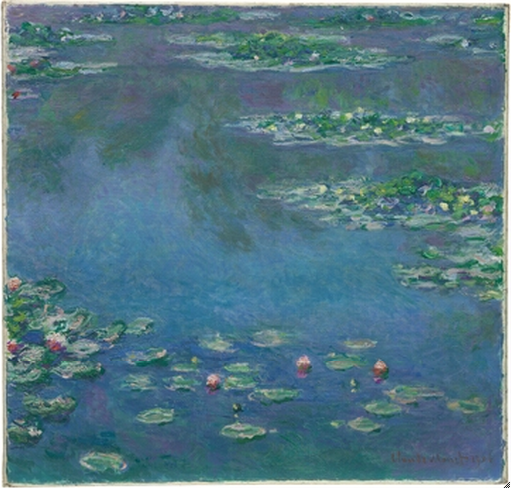

Cat. 47

Water Lily Pond

1917/19

Oil on canvas; 130.2 × 201.9 cm (51 1/2 × 79 1/2 in.)

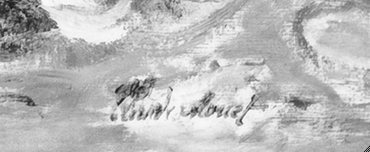

Estate stamp formerly at lower right: Claude Monet

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Mrs. Harvey Kaplan, 1982.825

Revisiting the Water Lily Pond

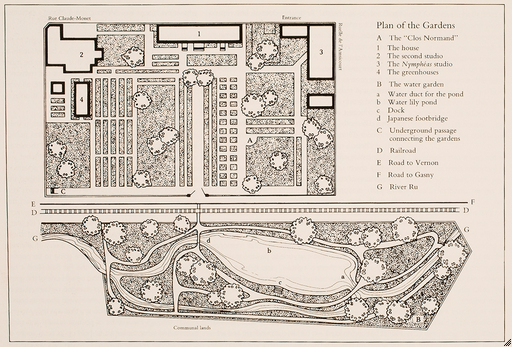

With the exception of his series of London (see cats. 38–41) and Venice (see cat. 45) paintings, Claude Monet primarily focused his attention after 1899 on painting the water lily pond that he had built and gradually expanded on the property at his Giverny home (fig. 47.1). Water Lily Pond is an example of Monet’s continued passion for the subject in the later years of his life, and this particular painting, as characterized by Impressionist scholar Gloria Groom, “emerged out of his competing desire to make mural-like pictures that would create an all-over decorative environment.”

The emphatically horizontal Water Lily Pond was likely executed between 1917 and 1919, one of a group of nineteen paintings that featured the pond’s surface, studded with clusters of floating water lilies and impressions of the sky reflected. These were significantly larger than the artist’s earlier paintings of this subject (see cat. 37 and cat. 44); five were originally 130 × 200 cm and fourteen, 100 × 200 cm. Monet created these paintings as part of his process of working up to the three-, four-, and five-meter panels that he officially offered to the French nation in 1922 and that were installed in the Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, in 1927 (fig. 47.2).

Rejuvenating the Decoration

Monet had mentioned a decoration project as early as August 1897 to writer Maurice Guillemot, who had traveled to Giverny to interview the artist. Recalling his conversation with Monet, part of which took place under a parasol on the bank of the pond, Guillemot described the setting and the decorative project that was percolating in Monet’s mind: “The oasis is [the most] charming of all the models he decided on; for these are the models for a decoration, for which he has already begun to paint studies, large panels, which he showed me afterward in his studio. Imagine a circular room in which the dado beneath the molding is covered with [paintings of] water, dotted with these plants to the very horizon, walls of a transparency alternately green and mauve, the calm and silence of the still waters reflecting the opened blossoms. The tones are vague, deliciously nuanced, with a dreamlike delicacy.”

It was not until April 30, 1914, that Monet returned to this idea with renewed interest: “I am even planning to embark on some big paintings, for which I found some old attempts in a basement,” Monet wrote to his friend the art critic Gustave Geffroy. “Clemenceau saw them and was amazed. Anyway, you’ll see something of this soon, I hope.” By late May or early June 1914 Monet had begun work, and the following January, he first described the endeavor as his Grande décoration, “a project that I have been involved with for some time already; water, water lilies, plants, but on a very large scale.”

Leaving the Studio

Monet was very reluctant to let outsiders see his work in progress on the Grandes décorations, and most of the preparatory studies, like Water Lily Pond, never left Monet’s studio until well after his death, when they were rediscovered in the 1950s. Indeed, Water Lily Pond once bore the Monet estate stamp that was applied to works that left posthumously (see Technical Report; see also cat. 46). This did not deter dealers and collectors from trying to acquire them, however. In June 1920, Joseph Durand-Ruel came to Giverny with Mrs. Charles (Sara) Hutchinson (wife of the president of the Board of Trustees of the Art Institute of Chicago) and Chicago collectors Mr. and Mrs. Martin Ryerson to negotiate purchase for the museum of what was later reported to be thirty paintings for three million dollars (fig. 47.3).

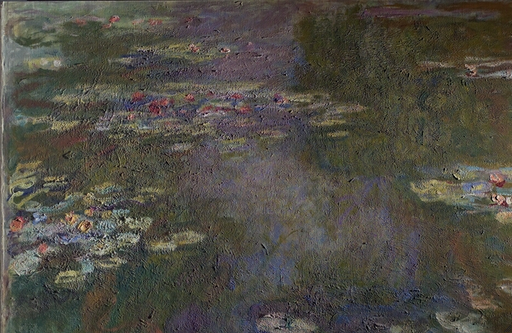

Monet allowed several of the nineteen large-scale works from the 1917–19 Water Lily Pond series to leave the studio. He sold four to Bernheim-Jeune in November 1919 and donated one in 1922 to the Société d’Initiative et de Documentation Artistique in Nantes. The art historian Paul Tucker has argued that Monet relinquished these paintings so that he could reengage with the public market, for he had only parted with a handful of works since his sale of Venice pictures to Bernheim-Jeune in 1912. These canvases, all signed and dated by Monet, provide an interesting comparison with the Art Institute’s related, but unfinished Water Lily Pond. For example, in contrast to the slightly smaller Water Lilies (fig. 47.4), now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Tucker notes that the Art Institute’s painting “is more agitated and uncertain. Even the water lily pads appear both less defined and more independent, although they occupy essentially the same locations as in the finished picture. Moreover, the balance between the foliage and the reflections of sky in the water is more precarious.” Also notable are the areas of exposed ground around the edges and corners of the Chicago canvas (see Technical Report). Monet was known to finish these areas last, just before giving it to a buyer.

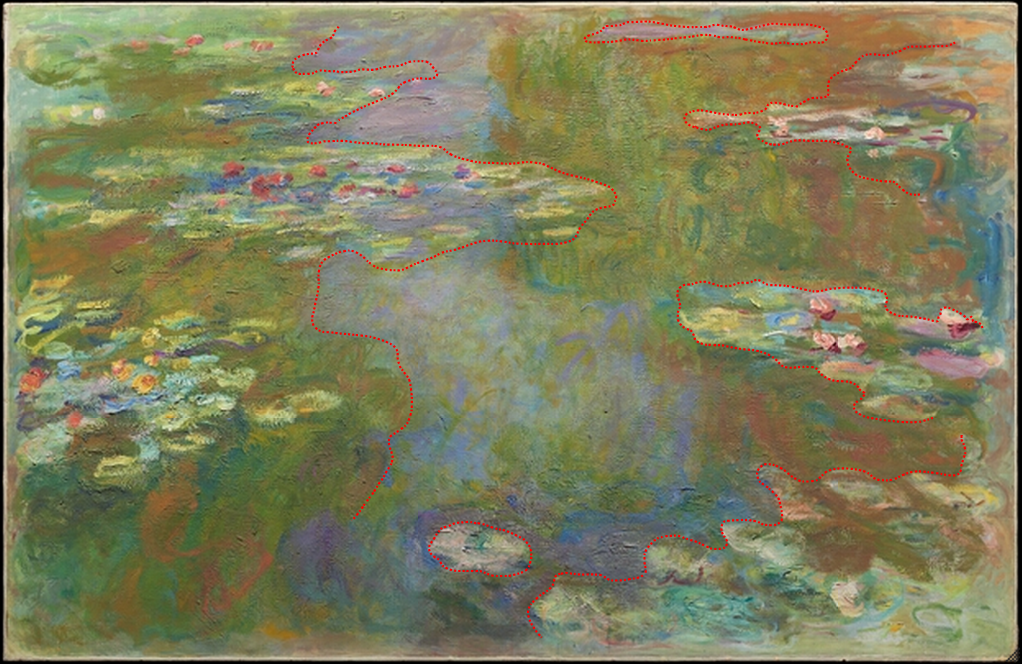

Building up Water Lily Pond

In terms of the scale of the canvas and the size of the brushes used, Monet’s Water Lily Pond differs greatly from his earlier series of water lily pond paintings that he executed between 1903 and 1908 (see cat. 44 and fig. 47.5). In both, Monet eliminated evidence of the banks surrounding the pond, and focused solely on the surface of the water. The two works also reveal the importance that Monet placed on the location of the water lily groupings in his overall compositions. As with his painting from 1906, Monet meticulously experimented with the placement of the clusters in Water Lily Pond as he developed other aspects of the picture; the ovoid shapes were changed, added, and removed at different times in each painting’s development. Notably, Monet added the floral elements in multiple phases before and after he worked up the complex reflections in the surface of the water.

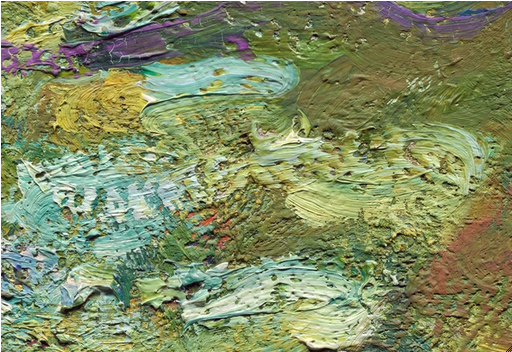

The way in which Monet tweaked the floating floral groupings in Water Lily Pond is one indication that while the painting was a preparatory work, it was not one that Monet executed quickly or without sustained effort. Technical examinations further reveal that he spent significant time working up Water Lily Pond. Over the course of a number of sessions, Monet created a thickly painted and highly textured surface in a series of wet-over-dry paint applications (see Technical Report). Although the painting was not considered “finished” by Monet, the complex topography (see fig. 47.6) of the surface that he developed could only have been undertaken over a sustained period of time.

Jill Shaw

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Claude Monet’s Water Lily Pond was painted on a pre-primed linen canvas, the dimensions of which are slightly larger than the largest advertised standard-size canvas, indicating that it was probably custom ordered. The ground consists of a single, off-white layer. Most of the painting was thickly built up in a series of wet-over-dry paint applications, resulting in a highly textured surface. The edges and corners, on the other hand, were much more loosely painted using very thin washes of color that barely cover the ground layer, followed by a few isolated, brushmarked strokes. Most of the thin paint around the edges was applied in the initial painting stages and passes underneath the more built-up paint of the interior of the composition, but additional paint was also applied to the edges after the painting was finished. The water lilies were added in two stages: both before and after the reflections of the foliage on the water were painted. As a result, some of the earlier flowers are partially or wholly obscured from view in the final composition. The water lilies visible on the surface were painted using thick impasted strokes, often applied wet-in-wet and with two or more unmixed colors picked up on the brush. The paint has a noticeably dry, matte surface appearance. An estate signature stamp was documented in the lower right corner in a 1963 photograph. The stamp was removed, probably when the painting was cleaned and lined before entering the Art Institute’s collection.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 47.7).

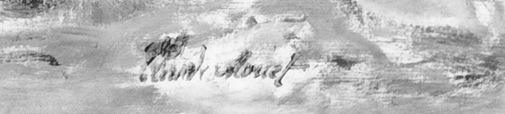

Signature

A black-and-white photograph taken in 1963 shows an estate signature stamp in the lower right corner: Claude Monet (fig. 47.8). It is not known when, why, or by whom this estate stamp was removed, but it was probably done when the picture was cleaned and lined prior to entering the Art Institute’s collection.

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions were approximately 130 × 200 cm. This is slightly larger than the largest available standard-size canvas, a no. 120 (130 × 195 cm). The canvas was probably custom ordered.

Weave

Plain weave. Average thread count (standard deviation): 26.8V (0.5) × 22.1H (0.9) threads/cm; the vertical threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the horizontal threads to the weft. No weave matches were found with other Monet paintings analyzed for this project.

Canvas characteristics

There is fairly regular, pronounced cusping on the left and right edges. Cusping on the top and bottom edges is milder and corresponds to the placement of the original tacks.

Stretching

Current stretching: Dates to lining carried out prior to acquisition (see Conservation History). Copper tacks spaced approximately 7–10 cm apart. The current stretcher is slightly larger than the original, and as a result, approximately 0.5–1.0 cm of unpainted priming from the tacking margins is now visible around the edges of the painting.

Original stretching: Tacks spaced approximately 10–12 cm apart (5–6 cm apart near the corners).

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: ICA spring stretcher; probably dates to preacquisition lining treatment (see Conservation History). Depth: Approximately 3.5 cm.

Original stretcher: Discarded, not documented.

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

None observed in current examination or documented in previous examinations.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

The ground extends to the edges of the top and bottom tacking margins but stops short of the left and right edges. This indicates that the canvas was cut from a larger piece of primed fabric on the top and bottom edges. The left and right edges probably correspond to the original edges of the larger fabric, which were attached to the commercial priming frame. The ground consists of a single layer that ranges from approximately 40 to 115 µm in thickness (fig. 47.9).

Color

The ground is off-white with some dark particles visible under magnification (fig. 47.10).

Materials/composition

Analysis indicates that the ground contains lead white and barium sulfate with traces of calcium sulfate and bone black. Binder: Oil (estimated).

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No underdrawing was observed with infrared reflectography (IRR) or microscopic examination.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

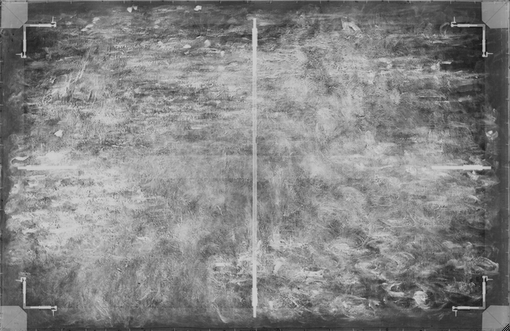

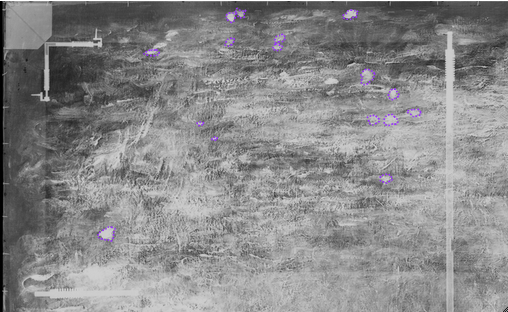

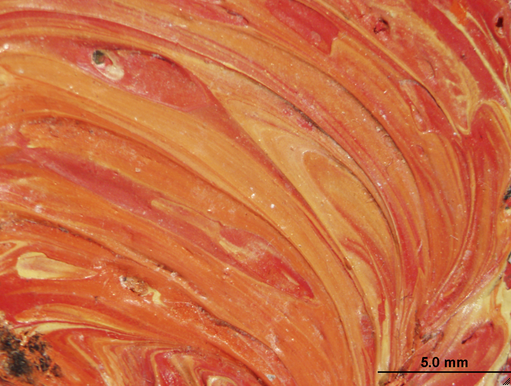

Although the work may appear to be quite openly painted with thin, wispy brushstrokes and sketchy edges and corners, it was actually built up in numerous superimposed layers of thick paint, culminating in a highly textured surface. The rough surface topography is due to both underlying and surface layers (fig. 47.11, fig. 47.12). The X-ray further reveals a dense mass of brushwork covering most of the canvas (fig. 47.13). Toward the edges and especially at the corners, on the other hand, the work is much more thinly painted, with the ground layer left exposed in places (fig. 47.14). In these areas, the artist used very thin washes of translucent color that present a flat, matte surface and leave the texture of the canvas weave evident (fig. 47.15); in places, the ground layer remains exposed between brushstrokes. This peripheral paint appears to have been significantly thinned with solvent, and a few drip marks are visible on the surface (fig. 47.16). For the most part, these washes appear to have been applied in the initial painting stages since they extend underneath the thicker paint buildup of the interior of the composition. Examples of this include the upper right corner where the thin orange and green layers extend underneath the thicker, brush-marked strokes (fig. 47.17) and at the left side, where the flower was painted on top of the thin green paint originating from the edge (fig. 47.18). In a few places, however, paint from the edges passes over the more worked-up areas of the painting, indicating that at least some of the edge strokes were later additions. This is evident in places along the bottom edge (fig. 47.19). In addition, in one area, near the upper left corner, some thin, pale-green paint passes over a thick, dark-green stroke from the more built-up area of the painting. The pale green can also be seen to extend over a few small losses of the paint and ground layers in that area (fig. 47.20), suggesting that the edges may have been reworked after the artist's death.

The corners and edges may give some indication of the general lay-in of the work. In these areas, on top of the first, thin washes, the artist began building up texture with low-relief brushmarks applied broadly in long, curving strokes (fig. 47.21). However, the dense brushwork in the more worked-up area of the painting makes it difficult to trace the progression of the painting process. Close examination of the X-ray shows both long, directional strokes, in every orientation, and more curving, circular strokes (fig. 47.22). The underlying brushwork seems unrelated to specific forms in the final composition and does not appear to represent any legible pentimenti. It is difficult to say whether earlier forms were painted out, but it does seem that much of this brushwork was designed to build up a network of color and texture that contributes to the final appearance of the painting. This is evident, for example, in the way that lighter colors from earlier paint layers show through small breaks in the brushwork applied on top (fig. 47.23), and the way that the texture of underlying brushmarks remains evident even when covered by subsequent layers of paint (fig. 47.24). Texture from the earlier layers is actually emphasized by the artist’s technique of applying fairly thin, light-handed strokes that graze the peaks of the already dry brush ridges and impasto underneath, creating a sort of corrugated texture on the surface (fig. 47.25). The fact that the painting was carried out with multiple layers of wet-over-dry paint application suggests that the work was executed in several sessions.

The foliage reflected on the surface of the water was created with strokes of thin, opaque paint in earthy tones of green, brown, and red (fig. 47.26). The water lilies seem to have been added in two phases, both before and after the reflections were painted. The earlier flowers were ultimately mostly obscured by subsequent brushwork. The water lilies near the surface were typically laid in using short strokes of thick lead white–rich paint applied on top of the water (fig. 47.27). Most of the flowers appear in the X-ray as dense, relatively radio-opaque areas (fig. 47.28). Several additional, similarly dense strokes are also visible in the upper part of the X-ray, but are not apparent in the final composition, suggesting that other flowers were initially included but were subsequently painted over. Under close examination, the bright colors of the painted-out flowers sometimes remain visible through breaks in the brushwork. Water lilies were added and painted out at different stages of the painting process, as Monet continued to experiment with their placement and degree of prominence. This can be seen, for example, in the group of light-orange-red flowers near the upper right corner. Colorful brushstrokes to the left of and below the flower on the far left seem to be related to water lilies that were later painted over with the green and brown strokes from the reflections in the water (fig. 47.29) before the surface flower was added. The flower in the middle of the grouping was partially covered by the strokes of pale gray drawn horizontally across it. This gray paint continues underneath the flower on the right, which must have been added to the composition later (fig. 47.30). The clusters of water lily plants visible at the surface were painted using thick, impasted strokes, often with two or three incompletely mixed colors picked up on the brush (fig. 47.31, fig. 47.32). Thickly loaded brushstrokes were often swirled together wet-in-wet (fig. 47.33) or dragged so lightly across the painting that they skip over the surface in places (fig. 47.34); these latter strokes were frequently used to define the edges of the lily pads (fig. 47.35, fig. 47.36). Overall, the paint has a notably dry, matte surface appearance.

Painting tools

Brushes, including 1.0 and 2.0 cm width (based on width of brushstrokes).

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, cadmium yellow, cadmium orange, zinc yellow, vermilion, red lake, viridian, cobalt blue, ultramarine blue, and cobalt violet. The presence of a bright-orangey-pink fluorescence under UV light suggests that the artist used red lake in the flowers.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting is currently unvarnished. A synthetic varnish, applied at an unknown date prior to acquisition by the Art Institute in 1982, was removed in 2005. During the 2005 treatment, it was noted that no traces of an earlier natural-resin varnish were evident. The painting has a generally dry, matte appearance with slightly more glossy areas in some areas of impasto.

Conservation History

There is no documentation of treatment carried out before the painting was acquired in 1982; however, at some point before the painting was acquired by the Art Institute, the canvas was wax-resin lined and stretched on an ICA spring stretcher, and a synthetic varnish was applied.

In 2005, the synthetic varnish was removed and the painting was left unvarnished.

Condition Summary

The painting is in good condition. The canvas is wax-resin lined and stretched taut and in plane on an ICA spring stretcher. There is general abrasion and tiny losses of the ground layer on the tacking margins and along the original foldovers. The paint layer is thickly built up over most of the surface, except at the edges and corners where thin washes of paint were used; some drip marks from the fluid paint application are visible on the surface. The corners and edges were painted, for the most part, in the early stages of work on the canvas, although in some places, particularly along the bottom edge, the washes extend over more built-up areas of the painting. In one place, near the upper left corner, this paint passes over a few small paint losses, suggesting that areas around the edges may have been reworked after the artist's death. There are fine drying cracks throughout much of the surface, which seem to be related to the layering of thin, lean paint over thick, slower-drying layers. There are a few small paint losses, mostly near the edges, that appear to be old. There are some random paint splatters near the bottom edge of the canvas. Fibrous tissue residues are visible in several places on the paint surface, probably from a facing applied during the lining. The painting is currently unvarnished.

Kimberley Muir

Frame

Current frame (installed in 2008): The frame is not original to the painting. It is an American, twenty-first-century reproduction of an early-twentieth-century, French, molding frame with a slight cushion profile. It is oil gilded over a black oil paint base. The pine molding is nailed and mitered at the corners (fig. 47.37).

Previous frame (installed by 1983; removed 2008): The work was previously housed in an American, mid-twentieth-century reproduction of a Louis XVI, gilt, architrave frame with carved outer ribbon-and-stave and inner ribbon ornament and an independent linen liner (fig. 47.38).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

By descent from the artist (died 1926) to his son, Michel Monet, Giverny.

Probably acquired by Katia Granoff, Paris, by Oct. 16, 1956.

Acquired by Paul Rosenberg, New York, by Oct. 16, 1956.

Sold by Paul Rosenberg, New York, to Mr. Harvey Kaplan, Chicago, Oct. 16, 1956.

By descent from Mr. Harvey Kaplan (died 1964) to his wife Mrs. Harvey (Ruth G.) Kaplan.

Given by Mrs. Harvey Kaplan, Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, beginning in 1982.

Exhibition History

Possibly Basel, Kunsthalle Basel, Impressionisten: Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Vorläufer und Zeitgenossen, Sept. 3–Nov. 20, 1949, cat. 203.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Collectors: An Exhibition Sponsored by the Men’s Council of the Art Institute, Sept. 20–Oct. 27, 1963, no cat. no. (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Monet, Mar. 15–May 11, 1975, cat. 121 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, July 22–Nov. 26, 1995, cat. 148 (ill.).

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 92 (ill.).

New York, Gagosian Gallery, Claude Monet: Late Work, May 1–June 26, 2010, no cat. no. (ill.).

Selected References

Kunsthalle Basel, Impressionisten: Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Vorläufer und Zeitgenossen, exh. cat. (Kunsthalle Basel, [1949]), p. 36, cat. 203.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Collectors: An Exhibition Sponsored by the Men’s Council of the Art Institute, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, [1963]), pp. 4; 52, pl. 41.

Denis Rouart and Jean-Dominique Rey, Monet, nymphéas, ou Les miroirs du temps, with a cat. rais. by Robert Maillard (Hazan, 1972), p. 174 (ill). Translated by David Radzinowiczas Monet, Water Lilies: The Complete Series, rev. ed., with a cat. rais. by Julie Rouart with Camille Sourisse (Flammarion/Rizzoli, 2008), p. 141 (ill.).

Susan Wise, ed., Paintings by Monet, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), p. 178, cat. 121 (ill.).

“Chicago Gets New Monet to Splash In,” Chicago (Oct. 1982).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Acquisitions,” Mosaic (Nov.–Dec. 1982), p. 6 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 4, Peintures, 1899–1926 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1985), pp. 288; 289, cat. 1889 (ill.).

Andrew Forge, Monet, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), pp. 66; 105, pl. 34; 109.

Charles F. Stuckey, with the assistance of Sophia Shaw, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Thames & Hudson, 1995), pp. 171, cat. 148 (ill.); 247.

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet, or The Triumph of Impressionism, cat. rais., vol. 1 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), p. 415, cat. 1889 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue raisonné/Werkverzeichnis, vol. 4, Nos. 1596–1983 et les grandes décorations (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), pp. 896–97, cat. 1889 (ill.).

Paul Hayes Tucker, with George T. M. Shackelford and Mary Anne Stevens, Monet in the 20th Century, exh. cat. (Royal Academy of Arts, London/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/Yale University Press, 1998), pp. 68–69, fig. 50 (ill.); 218.

Renate and Paul Woudhuysen-Keller, “Claude Monet’s Series L’Allée de Rosiers: History, Materials, Painting Technique—Removal of Over-paint,” in Monet: Atti del convegno, ed. Rodolphe Rapetti, Mary Anne Stevens, Michael Zimmerman, and Marco Goldin (Linea d’Ombra, 2003), p. 160, n. 8.

Alan G. Artner, “Art Institute given major Monet work,” Chicago Tribune, Aug. 25, 2005, section 5, p. 6 (ill.).

Gloria Groom, “Water Lily Pond,” in “Notable Acquisitions at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 32, 1 (2006), pp. 60 (ill.), 61 (detail), 95.

Joseph Baillio, “Katia Granoff (1895–1989): Champion of the Late Works of Claude Monet,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), pp. 39, fig. 12; 41.

James A. Ganz and Richard Kendall, The Unknown Monet: Pastels and Drawings, exh. cat. (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute/ Yale University Press, 2007), pp. 268; 269, fig. 273, 270.

Eric M. Zafran, “Monet in America,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), p. 140.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 25 (ill.); 163; 176–77, cat. 92 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 25 (ill.); 163; 176–77, cat. 92 (ill.).

Mary Mathews Gedo, Monet and His Muse: Camille Monet in the Artist’s Life (University of Chicago Press, 2010), pp. 228–29, fig. 15.7.

Paul Hayes Tucker, ed., Claude Monet: Late Work, exh. cat. (Gagosian Gallery, 2010), pp. 64–65 (ill.); 113.

Paul Hayes Tucker, “Monet: Public and Private,” in Claude Monet: Late Work, ed. Paul Tucker, exh. cat. (Gagosian Gallery, 2010), p. 35.

Other Documentation

Paul Rosenberg Archival Documentation

Invoice, Oct. 16, 1956

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Number

Location: right tacking edge

Method: handwritten script

Content: 17 (fig. 47.39)

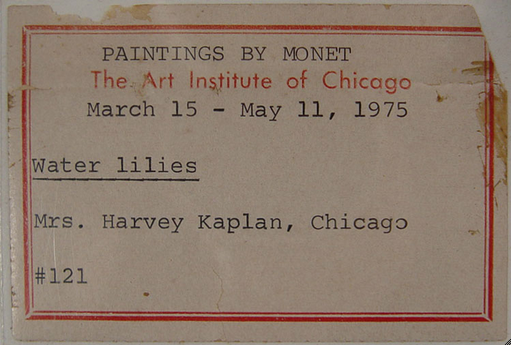

Pre-1980

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with typewritten script

Content: PAINTINGS BY MONET / The Art Institute of Chicago / March 15–May 11, 1975 / Water lilies / Mrs. Harvey Kaplan, Chicago / #121 (fig. 47.40)

Stamp

Location: lower right corner of painting

Method: stamp

Content: Claude Monet (fig. 47.41)

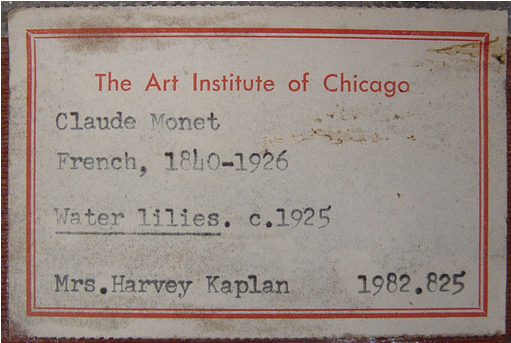

Post-1980

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label with typewritten script

Content: The Art Institute of Chicago / Claude Monet / French, 1840–1926 / Water lilies. c.1925 / Mrs. Harvey Kaplan 1982.825 (fig. 47.42)

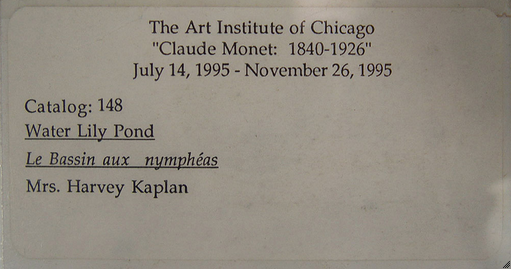

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: The Art Institute of Chicago / “Claude Monet: 1840–1926” / July 14, 1995–November 26, 1995 / Catalog: 148 / Water Lily Pond / Le Bassin aux nymphéas / Mrs. Harvey Kaplan (fig. 47.43)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter.

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis using a Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

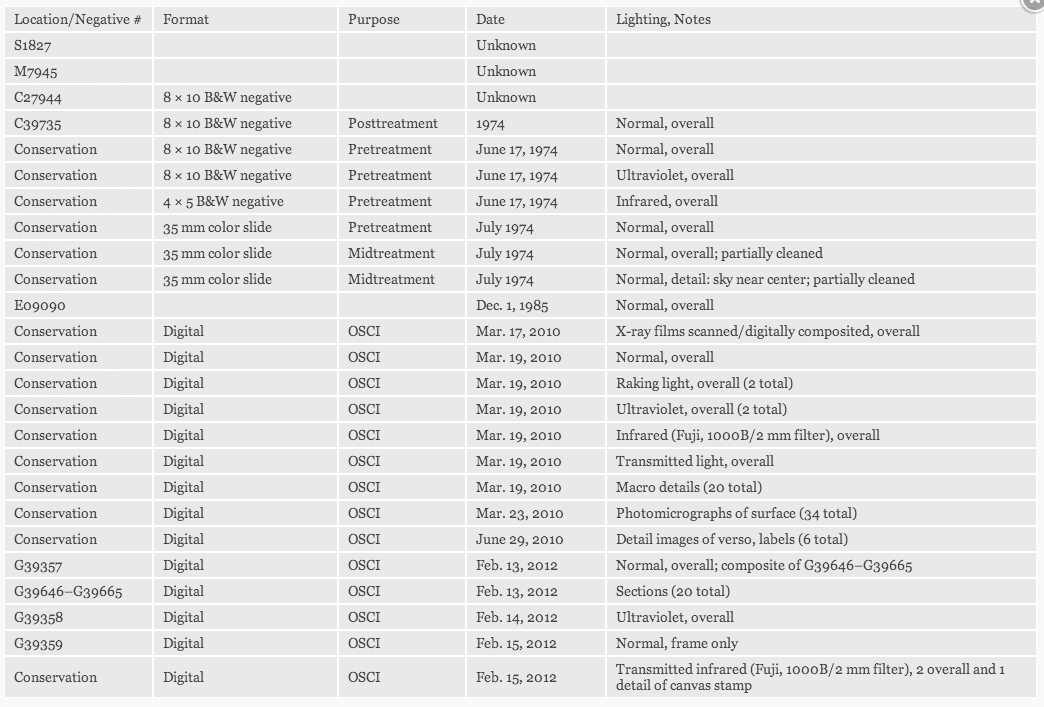

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 47.44).