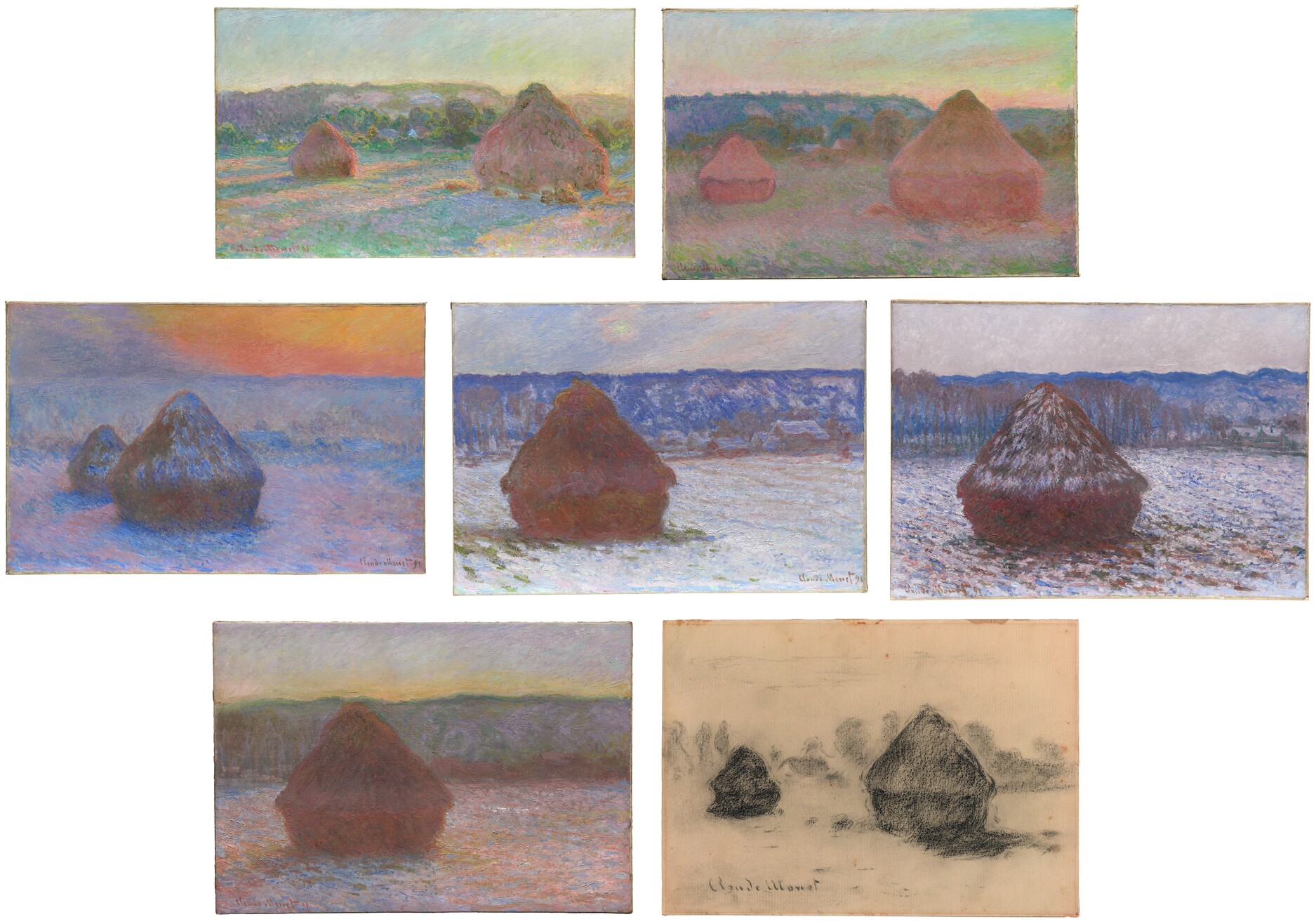

Cat. 27

Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer)

1890/91

Oil on canvas; 60 × 100.5 cm (23 5/8 × 39 9/16 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 91 (lower left, in orange-red paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Arthur M. Wood, Sr., in memory of Pauline Palmer Wood, 1985.1103

Cat. 28

Stacks of Wheat (End of Day, Autumn)

1890/91

Oil on canvas; 65.8 × 101 cm (27 7/8 × 39 3/4 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 91 (lower left, in red paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection, 1933.444

Cat. 29

Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect)

1890/91

Oil on canvas; 65.3 × 100.4 cm (25 11/16 × 39 1/2 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 91 (lower right, name in reddish-brown paint, date in greenish-brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Potter Palmer Collection, 1922.431

Cat. 30

Stack of Wheat (Snow Effect, Overcast Day)

1890/91

Oil on canvas; 66 × 93 cm (26 × 36 5/8 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 91 (lower right, in light reddish-brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1155

Cat. 31

Stack of Wheat

1890/91

Oil on canvas; 65.8 × 92.3 cm (25 15/16 × 36 3/8 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 91 (lower left, in brownish paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, restricted gift of the Searle Family Trust; Major Acquisitions Centennial Endowment; through prior acquisitions of the Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson and Potter Palmer collections; through prior bequest of Jerome Friedman, 1983.29

Cat. 32

Stack of Wheat (Thaw, Sunset)

1890/91

Oil on canvas; 64.4 × 92.5 cm (25 3/8 × 36 7/16 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 91 (lower left, in light red paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Daniel C. Searle, 1983.166

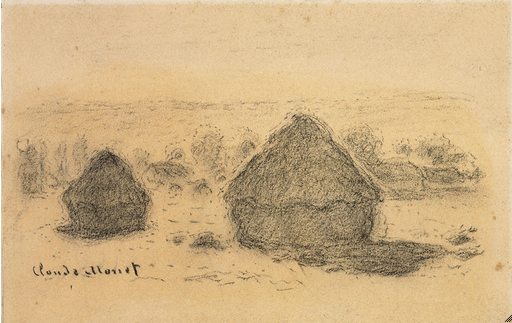

Cat. 33

Stacks of Wheat

1891

Black chalk, with stumping and frottage, on cream laid paper (discolored to tan), laid down on cardboard; 182 × 254 mm (primary/secondary supports)

Signed: Claude Monet (recto, lower left, in black chalk)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Dorothy Braude Edinburg to the Harry B. and Bessie K. Braude Memorial Collection, 2013.986

A Pivotal Moment

The year 1890 marked significant milestones for Claude Monet’s personal and professional career. In November he purchased the house in Giverny he had rented since 1883; the property and gardens there, which he went on to manicure and expand, would be a life-long source of inspiration. It was also in 1890 that the established leader of the Impressionists began work on his Stacks of Wheat. Although the concept of painting in series had occupied him for some time, this group marked a pivotal shift in his practice. Moreover, he established a new way of presenting his pictures when, in May 1891, fifteen Stacks featured in an exhibition at Durand-Ruel.

Monet executed the approximately twenty-five canvases that make up the series proper—six of which are now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago—likely between late August or early September 1890 and February 1891. As his work on the paintings drew to a close he made two drawings on the theme. He found his motif, with its hilly, tree-dotted backdrop, in a field adjacent to his property (fig. 1). The compositional placement of the stacks was of interest to Monet, as was his concern for getting their shapes just right. But perhaps more importantly, their form in the landscape served as a vehicle for formal experimentation: a chance to explore the enveloppe, the ephemeral and constantly changing atmospheric conditions that transformed his chosen scene.

Depicting "Instantaneity"

In what may be Monet’s earliest account of his work on the Stacks of Wheat, he touched on key points that distinguished the series from his previous efforts. “I’m working away at a series of different effects (of stacks), but at this time of year, the sun sets so quickly that I can’t keep up with it,” Monet explained to his friend Gustave Geffroy on October 7, 1890. “I’m becoming so slow in my work that it makes me despair, but the further I go, the better I see that it takes a great deal of work to succeed in rendering what I want to render: ‘instantaneity,’ above all the enveloppe, the same light diffused over everything, and I’m more than ever disgusted at things that come easily, at the first attempt.”

The fact that Monet called his new paintings a “series” appears to be a tantalizing self-reflection as he embarked on what would be a transformation in his practice, yet this was by no means the first time he had applied the label to his work. In fact, by the mid-1870s, Monet used it regularly to describe his versions of paintings on the same motif, such as his views of the Gare Saint-Lazare (see cat. 16 [W440]). A more significant point lies instead in his confession that his recent paintings did not come quickly or easily to him—and that he welcomed the challenge. If he hoped to depict “instantaneity,” somewhat ironically, it would take time. Tellingly, too, he worked up the Stacks of Wheat as a group, partially en plein air, partially in his studio. Soon this novel methodology—selecting isolated motifs to paint repeatedly under different atmospheric conditions—would become his typical working method.

As early as 1892, Monet reflected on this change in his practice, stating that his new aim was to explore “more serious qualities” in his art. But, as many art historians have noted, Monet’s choice of wheat stacks and other motifs, while formal exercises, often resonated deeply with the social context in which he lived and worked. After a period of extensive travel in the 1880s, Monet’s age, financial security and home ownership, seem to have reinvigorated his interest in depicting nearby rural themes. In picking the stacks of wheat as a subject, however, as Impressionist scholar Robert Herbert has argued, Monet tapped into the motif’s nuanced meaning within the local community at the time. “It is not a ‘haystack’ at all, but a grain stack,” Herbert clarified. “Haystacks . . . have slightly irregular, less architectural shapes. Grain stacks are built more carefully, their shocks first tied together and then actually thatched to keep the rain out . . . We are therefore not looking at ordinary hay, but at Stacks of Wheat (to give them their real title), wheat which was literally the wealth of its owners.” Later, Paul Tucker noted that Monet also connected with the patriotism and nostalgia that endeared images of the fertile and abundant French countryside to French society in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Promoting and Exhibiting Stacks of Wheat

Monet worked to promote the Stacks of Wheat in advance of the exhibition. Early in 1891, he agreed to provide Octave Mirbeau with illustrations for an article in L’art dans les deux mondes. Mirbeau had been deeply affected by his experience of the works: "We couldn’t tear ourselves away from contemplation of your Stacks, whose fair dream seems to expand, deepen to infinity.” He assured his friend that he would stay true to his subject: “Do believe me that in this article, in prophesizing the Monet you will become, I’ll be careful not to forget the one you are.” After the text appeared in print, however, Mirbeau reproached the publishers (who had held back proofs he wanted to amend). Nonetheless, this does not detract from the fact that the article marked an important moment in the critical reception of the works; the drawing that accompanied the text (see fig. 2, now in the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo) is remarkably similar to the Art Institute’s sheet.

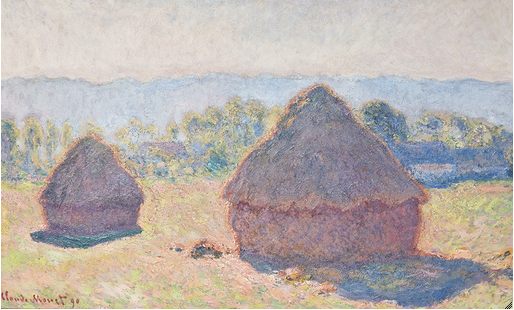

Monet based the Tokyo drawing on a painting of 1890 (now in the Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Conn. [fig. 3]). The Hill-Stead painting may well have prompted the Art Institute sheet, too, though it is difficult to establish which of the drawings came first. They are remarkably similar in detail, but it seems logical that the Chicago sheet was the earlier attempt, given that Monet—who made very few drawings at this stage of his career—would probably have been loath to make two studies if he had been satisfied with the first. Furthermore, in the Tokyo work the more abstract background lends prominence to the stacks. This simplification would have suited the purposes of reproduction, although Monet’s rendition of trees and buildings is perhaps more faithful to the painted composition.

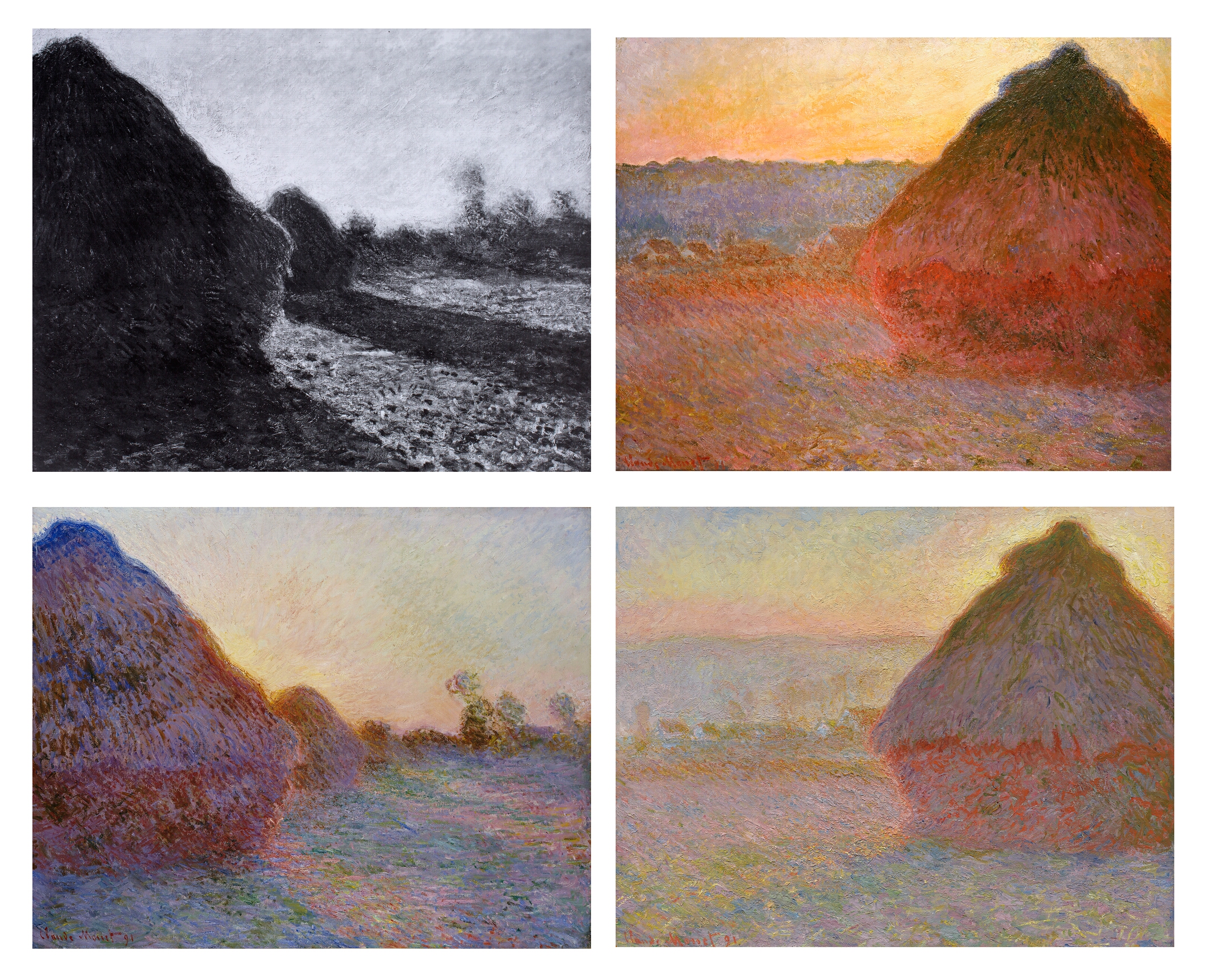

That Monet was challenged by the task of creating a representative image of Stacks of Wheat for print purposes is perhaps unsurprising. Monet’s painted images are characterized by their subtle variations of tone and their complex, textured surfaces, whereas black-and-white illustrations with distinct, clearly defined contrasts of light and dark tend to reproduce best. Monet adopted a monochrome palette but, by using soft black chalk in his drawing, avoided harsh contours. To mimic his distinctive stippled brushwork, he used a technique called frottage whereby the sheet is placed on an object and then rubbed to register the object’s textured surface. He outlined the stacks with wavering strokes and used stumping to work the chalk into the paper, creating an image with its own unique appeal.

For most commenters on the first exhibition of the Stacks of Wheat paintings at Durand-Ruel in May 1891, it was the installation that garnered discussion. In the preface to the accompanying catalogue, Gustave Geffroy noted that “the grouping together of fifteen canvases of haystacks, each representing the same subject, with a rendition of the same landscape, is an extraordinarily victorious artistic demonstration . . . [Monet] conveys the sensation of the ephemeral instant that comes into existence and never again returns, and at the same time, he constantly evokes in each of his canvases—through the weight, the power that comes out from the curve of the horizon, the roundness of the terrestrial globe—the course of the earth through space.” Dutch critic Willem G. C. Byvanck noted that the individual paintings “acquire their full value by comparison [to the others] and in the succession of the full series.” Little is known about the exact arrangement of the canvases in the show, for there are no extant photographs to confirm whether the works were hung sequentially by season, by size, or by another ordering principle. But what is known, from these accounts and others, is that fifteen Stacks of Wheat were shown together at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in one small room, a new strategy for the exhibition of Monet’s works. In addition, two of Monet’s 1886 figure paintings of a woman holding a parasol were reportedly hung above the row of Stacks; elsewhere in the room, Monet included four field pictures from 1890 and one painting from the Creuse series (see cat. 25).

Assessing the Series

The Art Institute holds the world’s largest number of Stacks, which offers an unprecedented opportunity to compare technical findings and thereby rethink long-standing assessments of the series. Scholars have sought to identify an underlying logic to the Stacks of Wheat series. This is a particularly difficult task since, as the art historian Paul Tucker has noted, Monet often manipulated public accounts of his working method—and nowhere more so than with regard to the Stacks of Wheat. Tucker has written that Monet “clearly wanted to establish the fact that he was not a programmatic artist, that he operated on instinct rather than intellect, and that he simply applied those instincts to the dictates of nature.”

Geffroy’s preface in the Durand-Ruel exhibition catalogue, together with Monet’s atmospherically and seasonally precise titles for the works in the show, has led to the misconception that the paintings “chart the passage of the sun across the stacks with such specificity that they collectively form a kind of chronometer.” As mentioned above, art historians noted long ago that Monet’s Stacks of Wheat were not executed quickly and on the spot but were rather the result of multiple sessions, with the artist making calculated and careful changes in his studio. Scholars have noted that underlying brushwork does not match up to forms on the surface, and pentimenti in numerous paintings reveal that Monet even moved the locations of his stacks within compositions.

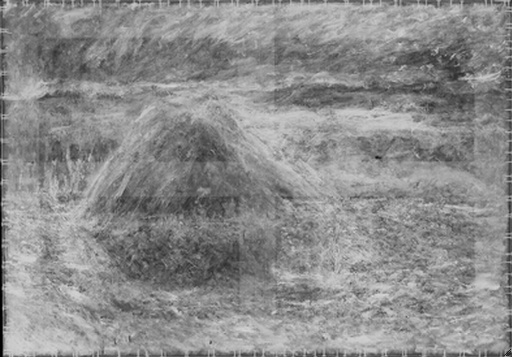

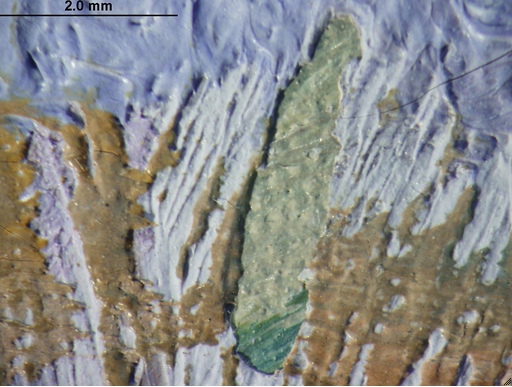

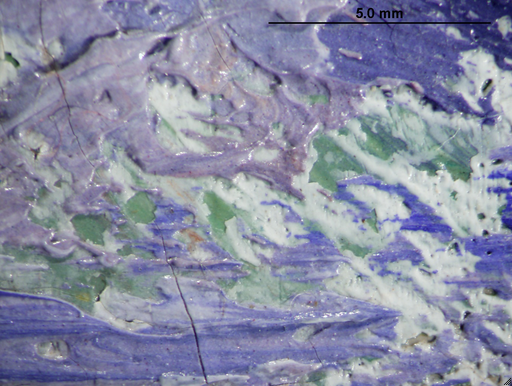

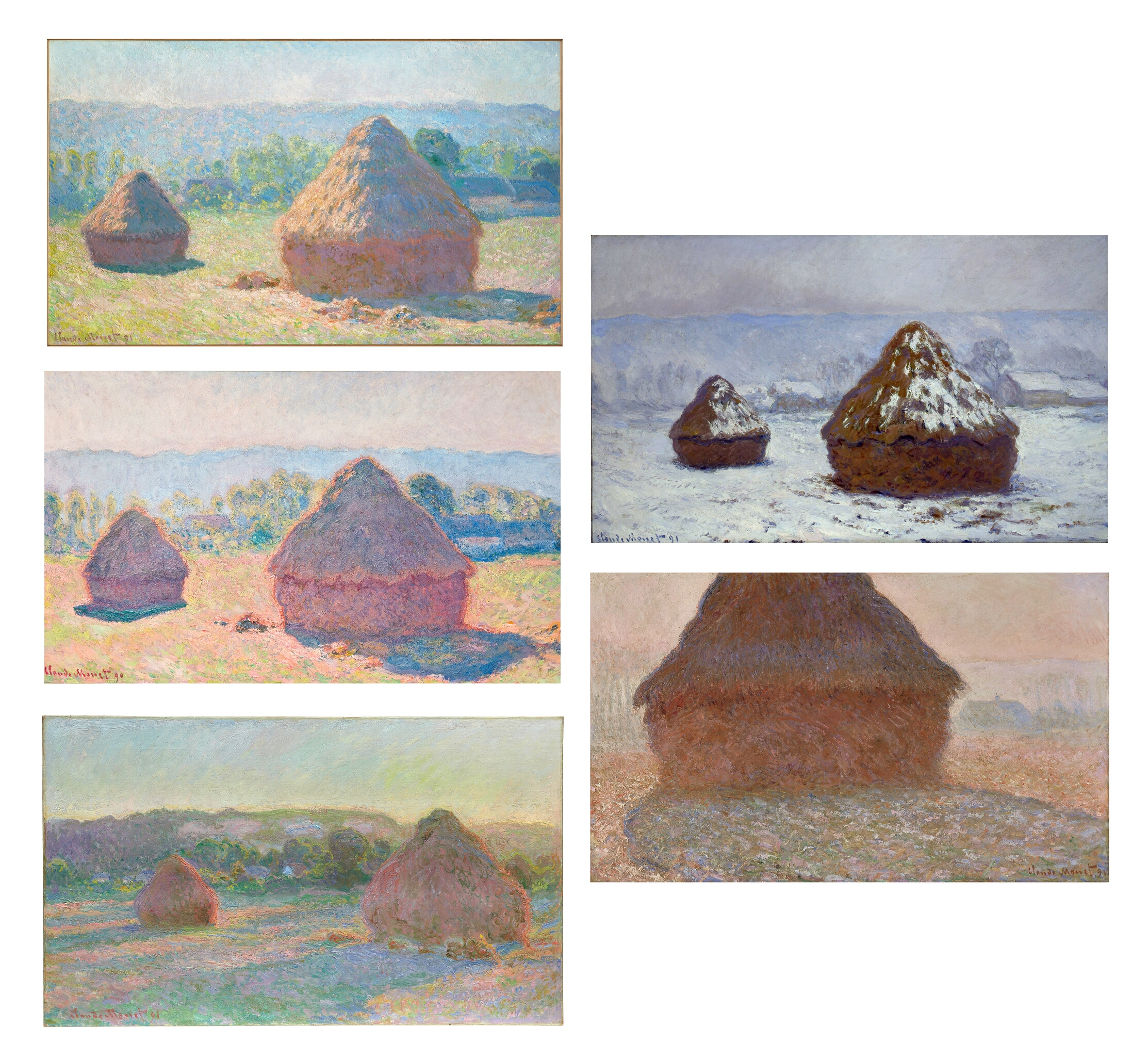

Recent technical examinations of the Art Institute’s six Stacks paintings support these contentions. All show evidence that Monet made changes to the paintings over the course of multiple working sessions. In Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer) (cat. 27 [W1269]), Stacks of Wheat (End of Day, Autumn) (cat. 28 [W1270]), and Stack of Wheat (Thaw, Sunset) (cat. 32 [W1284]), for example, Monet adjusted the shapes and sizes of the stacks and the placement of the horizon and houses in the background. Of these three, Stack of Wheat (Thaw, Sunset) shows the most dramatic change: [glossary:X-ray] and transmitted-infrared imaging reveal that Monet radically reduced the width of the stack (fig. 4). In some canvases, like Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect) (fig. 5) (cat. 29 [W1278]), Monet changed the placement of the stacks significantly, while in others, like Stack of Wheat (Snow Effect, Overcast Day) (cat. 30 [W1281]), he removed one whole stack entirely (fig. 6).

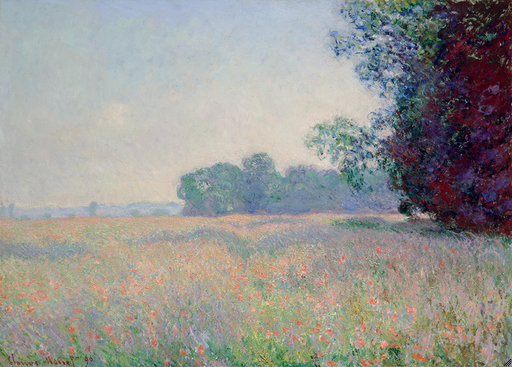

Perhaps even more significantly, two of the Art Institute’s paintings, Stacks of Wheat (Snow Effect, Overcast Day) and Stack of Wheat (cat. 31 [W1283]), both executed on no. 30 landscape ([glossary:paysage]) standard-size canvases, may have initially featured stacks in a different season or may have been painted over different compositions altogether. The two paintings reveal that, in initial layers, the landscape was at least partially green in places (fig. 7 and fig. 8), suggesting that the scenes did not originate as snowy ones from the winter of 1890–91 but rather from an earlier time in the year when the grass was still green. Losses in Stack of Wheat also reveal areas in which a vibrant red color appears. In each of these paintings, Monet covered the earlier composition with white paint that obscured the forms and textures of the painting underneath. The palette of the earlier layers suggests that these paintings could have begun as one of the paintings from summer 1890, featuring the oats, hay, or poppies that surrounded Monet’s property at Giverny (see cat. 26 [W1253]), that were put aside by the end of August when Monet began his Stacks of Wheat canvases. The similarity in palette and canvas size indicates that Stacks of Wheat (Snow Effect, Overcast Day) and Stack of Wheat may have begun in a fashion that was more analogous to works like Monet’s Prairie à Giverny (Prairie at Giverny) (fig. 9 [W1247]) or Champ d’avoine (Oat Field) (fig. 10 [W1259]).

A Different Look at the Series

Recognizing that Monet made such extensive changes to his paintings seems to have discouraged some art historians from theorizing any internal logic to the Stacks paintings. In his groundbreaking catalogue of Monet’s series paintings from the 1890s, Paul Tucker noted that the Stacks of Wheat paintings “are not all the same dimensions” and that “Monet clearly did not feel obliged to choose a particular-size canvas for a particular effect, season, or stack configuration.” New technical evidence from the Art Institute’s paintings, however, suggest that we revisit this theory as possible patterns in Monet’s Stacks of Wheat may, in fact, be discerned.

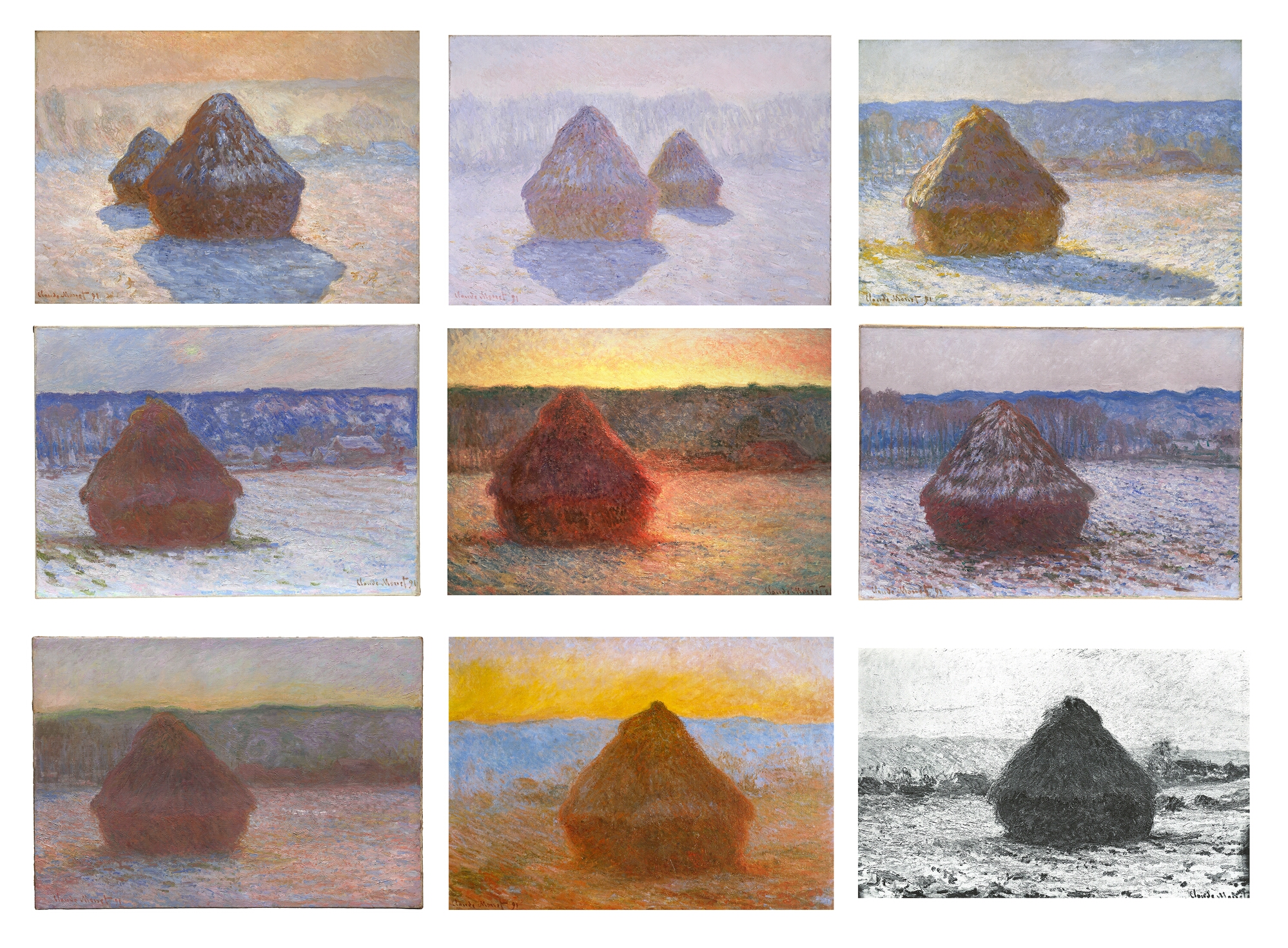

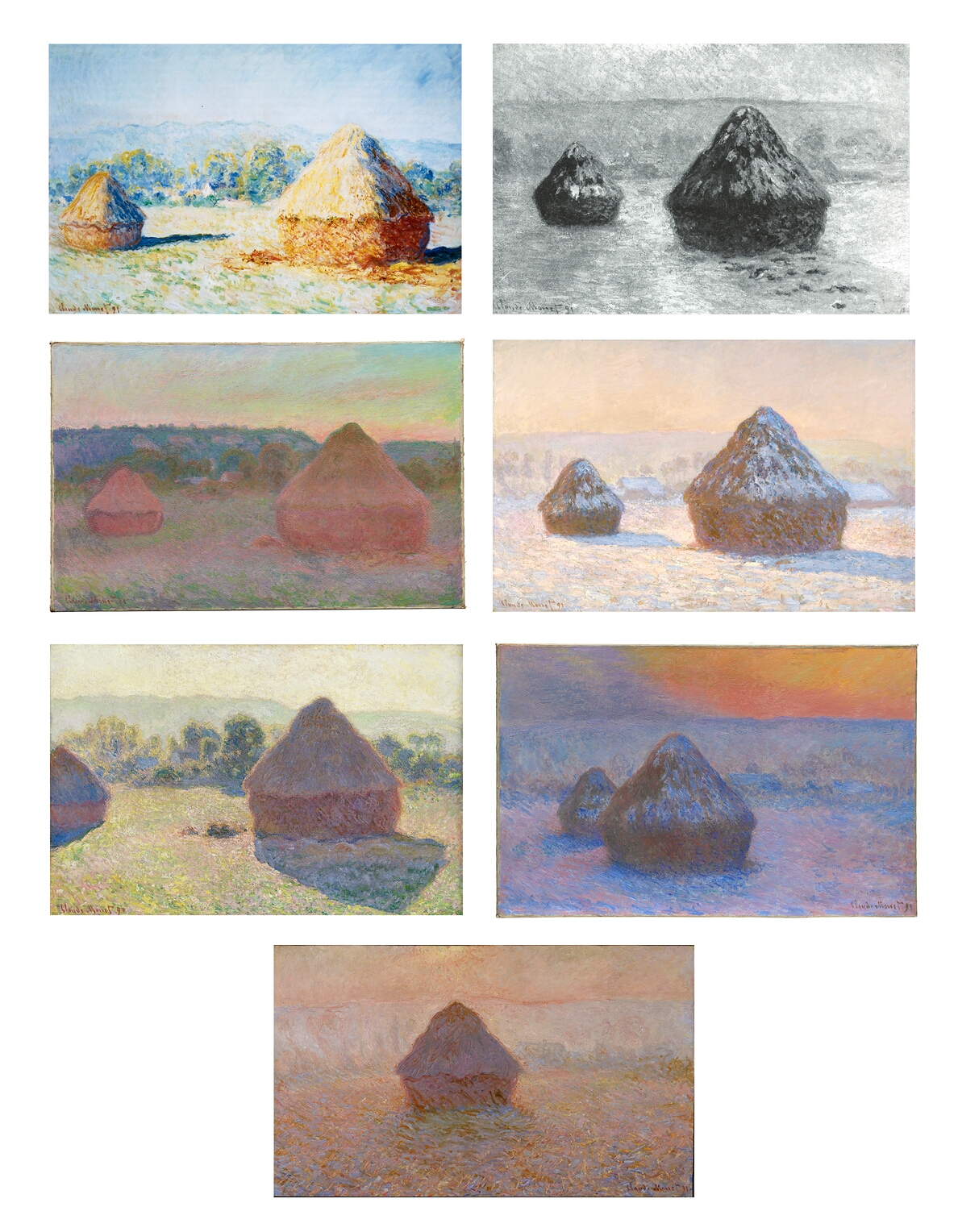

Monet consistently used four canvas sizes for his Stacks of Wheat paintings. Five paintings are executed on a non-standard-size format (60 × 100 cm; fig. 11); seven are painted on standard-size no. 40 [glossary:marine] format canvases (65 × 100 cm; fig. 12); nine are on standard-size no. 30 paysage format canvases; (65 × 92 cm; fig. 13) and four are executed on standard-size no. 30 [glossary:figure] format canvases (73 × 92 cm; fig. 14). Notwithstanding some exceptions, basic patterns emerge at first glance: four out of the five non-standard-size canvases (60 × 100 cm) feature two separated stacks of different sizes; six out of the seven works on no. 40 marine size canvases feature two stacks, although their placement is not consistent; the majority of the paintings on no. 30 paysage canvases depict single stacks; and finally, the standard no. 30 figure format canvases were reserved for those paintings depicting extremely close-up views of stacks that extend beyond the right or left edges of the picture plane.

While certain anomalies to these patterns are visible on the final canvases, features underneath the surfaces of these paintings must be further explored to advance the possibility that Monet might have started the Stacks more programmatically. For example, the Art Institute’s Stack of Wheat (Snow Effect, Overcast Day) complicates the suggestion that the no. 30 paysage canvases could have been primarily reserved for single-stack compositions. While [glossary:infrared reflectography] shows that Monet did at one time have a second stack located to the right of the stack in the final canvas, it is not clear that that second stack was included from the very beginning. X-ray shows that the landscape once extended beneath the stack, possibly indicating that the work started as a single-stack work before a second stack was added and later painted out.

While most of the no. 40 marine size canvases feature two stacks, those in Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect) [cat. 29] as well as Grainstacks in the Sunlight, Midday ([W1271]) are positioned differently from the others. Technical analysis of the former, however, shows that originally Monet did have the two stacks placed much more in line with those in the other pictures in this group. Research has also shown that the stack extending past the edge of the left side of the canvas in Grainstacks in the Sunlight, Midday had also been moved from a position that looked more like the other pictures in the group.

Variations on the Theme

Much has been written about the Stacks of Wheat as a unified group, and rightly so, for, as John House argues, “In exhibiting his series, Monet explored the possibilities of large pictorial ensembles, with the individual canvas an integral part of a larger entity . . . the cumulative effect he sought in his exhibitions began to affect the ways in which he executed his canvases, whereas before he had finished them piecemeal and without thought of establishing such an inner coherence. As much as the individual paintings themselves, the ensembles of his exhibitions became the end product towards which he worked.” While it is important—as House notes—that we consider Monet’s execution of the series as a group, the Art Institute’s analysis of its six Stacks of Wheat suggests that we should not ignore the complexities of the individual paintings. The techniques Monet used are tremendously varied and reveal the extent to which he labored over each work.

All of the Art Institute’s Stacks began on canvases that were probably commercially prepared and primed with an off-white ground. Technical examination shows that Monet exploited the tone of the ground to different extents. In Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer), for example, Monet used open brushwork throughout the painting, allowing areas of the ground to be exposed (fig. 15); in Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect) and Stacks of Wheat (End of Day, Autumn) the paint layers are more densely built up, and even in areas that are very thinly painted, the color of the ground is mostly obscured (fig. 16 and fig. 17). Also of particular note are canvases like Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer), Stacks of Wheat (End of Day, Autumn), and Stack of Wheat, in which Monet built up the sky using undulating zigzag strokes, much like those that he would also use to execute his Sandvika (cat. 34); in other Stacks, these distinctive strokes in the sky are not visible. Paintings like Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer) juxtapose thick impasto with very thinly painted passages and sometimes use paint that appears to have been manipulated by the artist to increase the fluidity (see Technical Report), while others like Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect) incorporate very little impasto, resulting in a brushmarked but relatively flat surface. Stacks of Wheat (Thaw, Sunset) is significantly different from the other Stacks paintings since Monet built up the surface of the foreground from dark to light. Whereas the other works were typically laid in with subdued tones and then built up using more intense color, in this canvas the artist also wiped or scraped areas of the canvas in an effort to expose underlying paint layers. This sample of the varying techniques Monet employed in the Art Institute’s Stacks. The Art Institute’s technical studies of its Stacks paintings pose more questions than answers, but one thing is clear: the varying techniques Monet employed in the works illustrate their incredibly experimental quality. The complex surface of each canvas suggests that the paintings in the series are not as homogeneous as is often assumed.

Jill Shaw