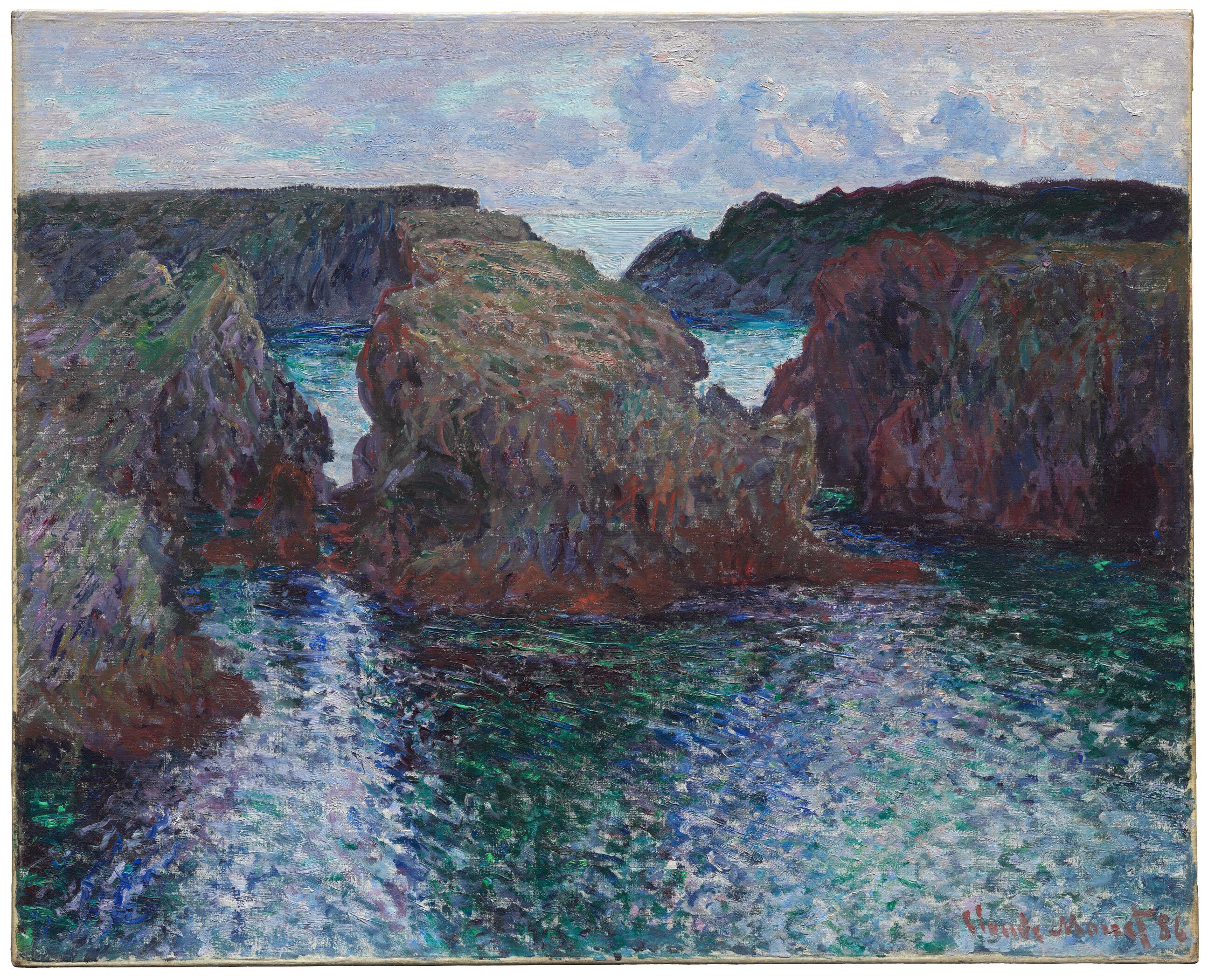

Cat. 24

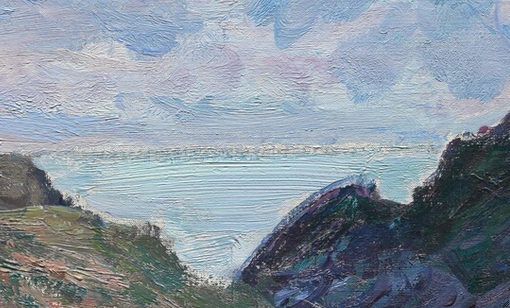

Rocks at Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île

1886

Oil on canvas; 66 × 81.8 cm (26 ×32 3/16 in.)

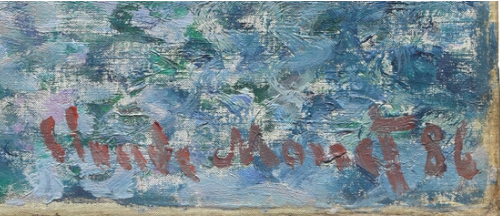

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 86 (lower right, in light orange-brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Chauncey B. Borland, 1964.210

An Isolated Destination

After spending the spring of 1886 working in Holland and the summer painting at home in Giverny, Claude Monet experienced a very different environment that fall on the remote island of Belle-Île off the coast of Brittany. His decision to travel to this rugged terrain may have been influenced by the novelist Octave Mirbeau, who had a country house on the nearby island of Noirmoutier; that year Monet had joined Mirbeau’s literary group in Paris, the Bons Cosaques (Jolly Cossacks). Fellow member and friend Pierre-Auguste Renoir had recently painted Breton landscapes, which may also have played a role in the choice. That same year Monet’s friend and patron Georges Charpentier published an account by the writer Gustave Flaubert of an 1847 trip to Brittany, which contained impressions of Belle-Île that could have piqued Monet’s interest in that specific destination.

Belle-Île was famous for its fantastic grottoes, cliffs, and aiguilles (or needles; pointed triangular rock formations also referred to as pyramids). Sparsely dotted with hamlets, Belle-Île had little tourist trade, which likely increased its appeal for Monet. In August the artist was making plans for a trip to Belle-Île, and with a stipend of 2,200 francs from his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, he left a month later. Monet intended to stay two weeks, but his campaign, as usual, became more complicated, and only at the end of November did he return, via a visit to Mirbeau in Noirmoutier, with some forty canvases for reworking at home.

Terrible Belle-Île

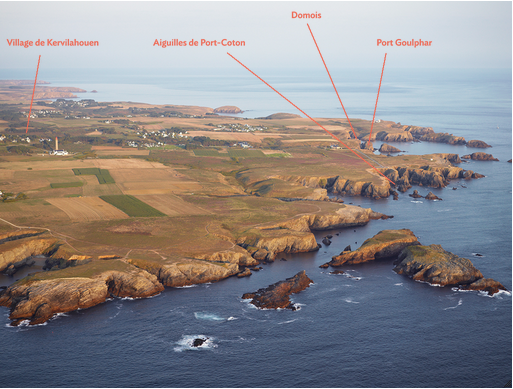

On September 12 Monet arrived at the town of Le Palais, a fishing port located on the eastern side of the island, and checked into the Hôtel de France. The following day Monet recounts to his companion, Alice Hoschedé, that he explored the island and saw beautiful things; however, he complained that Le Palais was “a real town,” too far from these locations that he had just discovered. Within days of his arrival on Belle-Île, Monet moved to Kervilahouen, a village of only ten houses on the other side of the island that was closer to the picturesque inlets scattered along the western side of the island, such as Port-Goulphar, an inlet studded with breathtaking rock formations (fig. 24.1). Monet rented a room in a modest house for four francs a day, which included meals of mostly eggs, fish, and lobster. As at Étretat the previous year, he roamed the cliffs and promontories, seeking out the most dramatic views. Instead of the beach with its evidence of human activity, however, at Belle-Île Monet focused on the ocean-ravaged rocks at Port-Goulphar, Port-Coton, and Port-Domois and the smaller outlying formations. Monet would treat these aspects of the Belle-Île coast in paintings that can be organized thematically into several subgroups, including ones depicting the Port-Coton pyramids (e.g., fig. 24.2 [W1084]), and the Lion Rock (e.g., fig. 24.3 [W1090]).

The decision to travel to Belle-Île was a radical departure for the artist, who when not working at home in Giverny stayed in relative comfort, as at the beachfront hotel at Étretat. Arguably the most physically challenging destination to date for Monet, the island was a desolate location. Monet struggled particularly with the tumultuous weather, which required him to hire a porter—the former lobsterman Hippolyte Guillaume, known as Poly (fig. 24.4). And yet the painterly potential of this unspoiled coastline fascinated the artist. In his letters to his dealers, friends, and Alice, he refers to Belle-Île as “sinister, diabolical, but superb” and “very beautiful but very savage;” admitting to his dealer “I am enthusiastic for this sinister land and precisely because it takes me out of what I am in the habit of doing.”

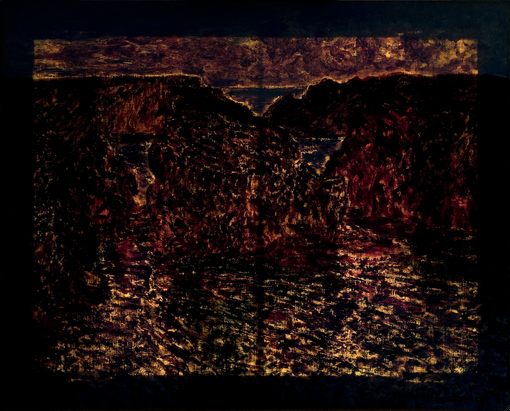

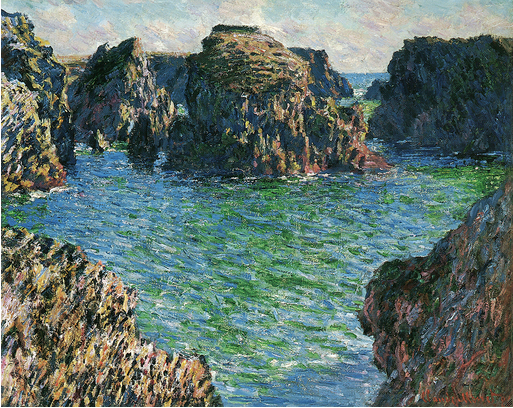

The Trio of Rocks at Port-Goulphar

The Art Institute’s painting is one of three versions anchored by the massive rock formations making up the Port-Goulphar (see fig. 24.5 [W1093] and fig. 24.6 [W1094]). In mid-October the island endured a weeklong tempest, documented by Monet in his correspondence. It is probable that he began the Port-Goulphar trio early in the month, prior to the storm. Depicting seemingly rare moments of reasonably calm seas, they show a range of weather conditions—sunny in Coming into the Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île (fig. 24.5), partly cloudy in Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île (fig. 24.6) and overcast in the Chicago picture. Of these three canvases, the Art Institute work is the only one that crops out the two flanking rocks, which are present at the bottom of the other two compositions. In a modern photograph that shows the approximate view that Monet chose for the Art Institute’s version (fig. 24.7), the cliffs that run along the outer edge of the Port-Domois are contiguous with the horizon. In another modern view of the inlet (fig. 24.8), comparable to the view seen in Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île, the signal station at Talut at the upper left is visible in the distance. Both Coming into the Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île and Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île are painted from spots similar to those seen in the modern photographs, but employ a lower vantage point, so that part of the cliffs at the horizon line on the right are obscured from sight. From the higher elevation of Rocks at Port-Goulphar, the modern photographs show that the signal station would have been visible at the upper left, but here it has been omitted, evidence of Monet’s “editing” for pictorial reasons. Further, from this elevated view, the border of cliffs and the horizon are exactly aligned with each other. The rocks in the middle ground seem closer to us yet the cliffs at the edge of Port-Domois are still visible in the background. The outer edge of the Port-Domois provides a decorative border on the horizon that counter balances the bulky masses of these rocks in the middle ground.

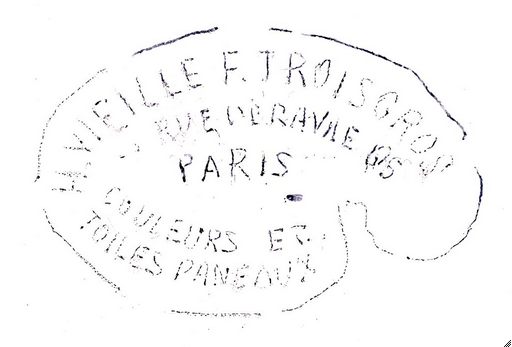

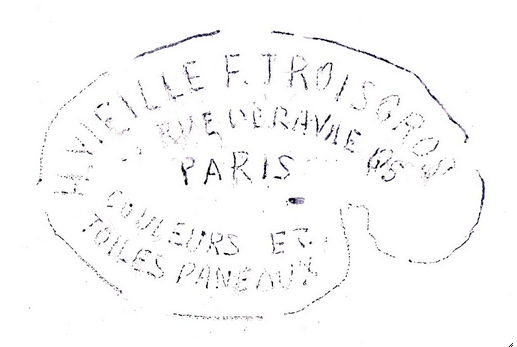

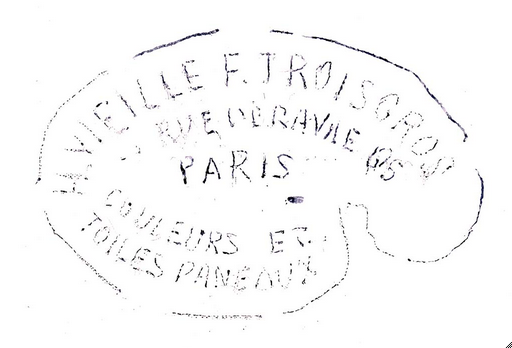

The Chicago painting’s canvas bears the stamp of the color merchant Vieille & Troisgros (fig. 24.9) and was found to have a warp-thread match with paintings from his previous Normandy campaign at Étretat (cat. 21 and cat. 23) indicating that Rocks at Port-Goulphar also came from the same bolt of raw canvas. Monet began his work at Belle-Île with four canvases; by October 11 he was repainting the unsuccessful canvases (“mauvaises toiles”) and waiting on "fresh” canvases that he had ordered from Troisgros Frères to be shipped to him. This new batch presumably would have borne the new Troisgros Frères canvas stamp rather than the now out-of-date Vieille & Troisgros stamp.

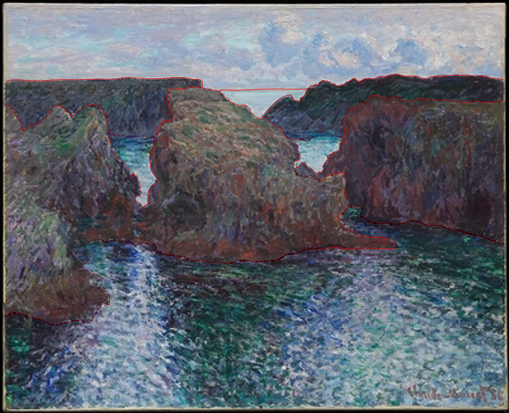

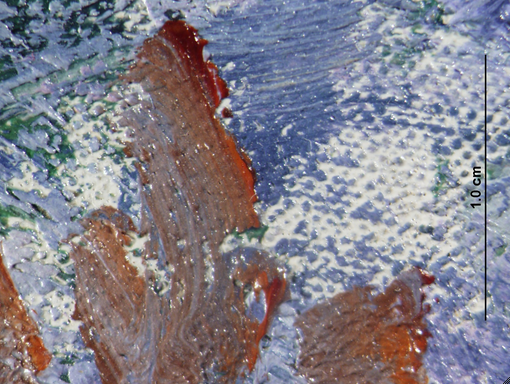

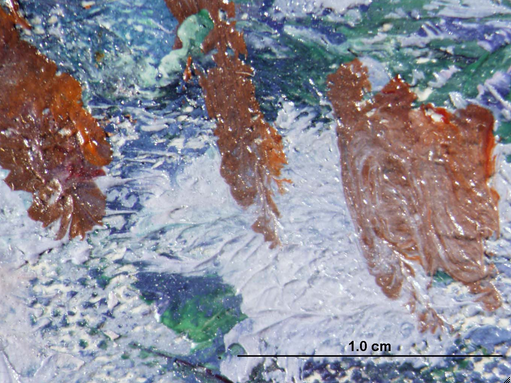

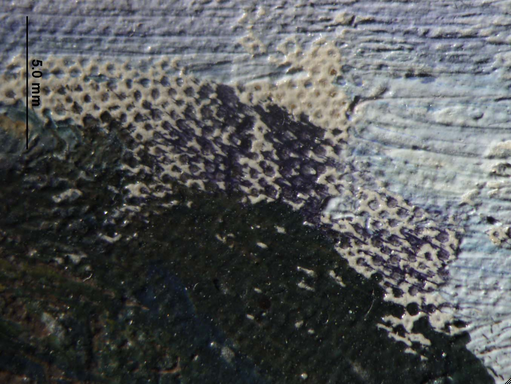

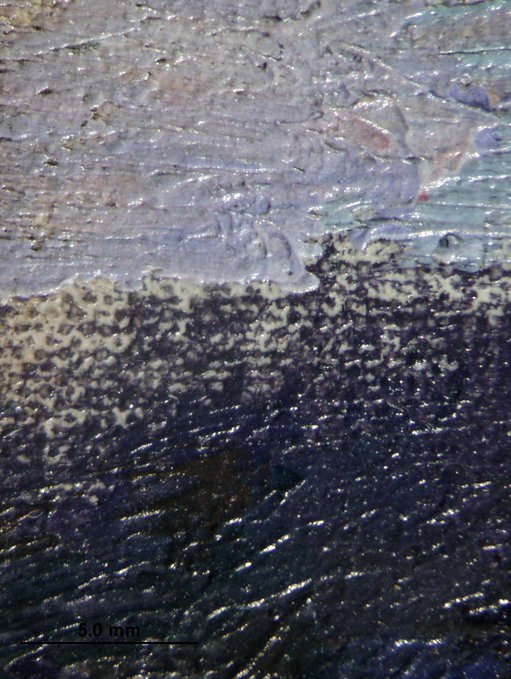

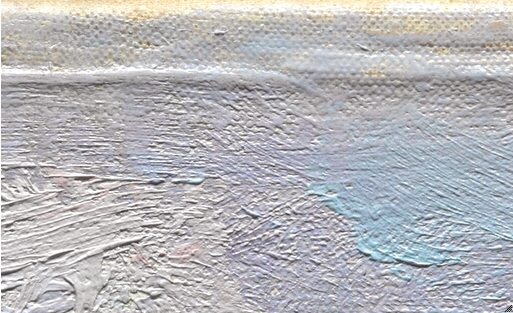

The Belle-Île group was likely conceived in Monet’s usual manner: finding, framing, and sketching in front of his motif, reworking the same canvas during the same or a later session, and making final assessments and retouches in his studio. For the Art Institute’s composition, on the other hand, Monet seems to have abbreviated his usual working process, painting more directly with minimal reworking. See, for example, the early delineation of the rocks, whose borders of exposed ground can be detected with the unaided eye (fig. 24.10). These masses, as well as the sky and water zones, were then filled in with a variety of brushstrokes worked wet-on-wet and in many areas only thinly applied (fig. 24.11). The horizon—interrupted by the top of the line of cliffs, which are delineated by a dark purple paint—was also asserted from the beginning (fig. 24.12). In comparison to the vertical Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île (fig. 24.6), dated 1887, whose elaborately variegated brushwork for the rocks and water suggests a greater degree of reworking, the changes to Rocks at Port-Goulphar seem minimal. The reddish-brown base of the cliff at the far left foreground has been extended slightly into the water. In addition, a few of the brighter strokes that were painted over already dried paint, notably the blue strokes under the signature (fig. 24.13), speak to additional painting session, possibly upon his return to his Giverny studio.

Success of the “Series”

These paintings of monumental and isolated rocks surrounded by water but devoid of human, animal, and even plant life were a personal, emotional response to the motif, an approach Monet would further develop in his series paintings of the 1890s (see cats. 27–32). In the context of Monet’s struggle with the elements while out on the cliffs of Belle-Île, his repeated use of the term “terrible” takes on a connotation different than the “terrible” sublime in nature sought by artists in the late eighteenth century. For Monet it indicated a powerful psychic force, both awesome and exhausting. Mirbeau, who came to visit Monet while he was working at Port-Goulphar, noted in a letter to Rodin that “[the Belle-Île paintings] will be a new aspect of his talent: a terrible and formidable Monet, unknown until now. But his works will please the common public less than ever.” On the contrary the art dealers Durand-Ruel, Theo van Gogh (representing Boussod & Valadon) and Georges Petit all believed the opposite and clamored to acquire the paintings as soon as Monet would allow them to leave his studio in 1887. In the spring of 1887, Monet exhibited at Georges Petit’s 6e Exposition internationale de peinture et de sculpture. Out of the twelve works by Monet listed in the catalogue, ten were from the Belle-Île campaign (including the portrait of his porter, Poly [fig. 24.4]). The Art Institute’s painting was not among those exhibited in 1887, but its closest cognate, Coming into the Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île (fig. 24.5), was both shown and purchased in 1887 by Petit and was no doubt the image the journalist Gustave Geffroy had in mind when he described the rocks as “Pachyderms with thick crusts.”

The two months at Belle-Île were physically and artistically arduous. And even now, as Denise Delouche has made clear in her comparison of Monet’s painting to the topography of Belle-Île, the cliffs and summits remain inaccessible except by foot and, even then, dangerous. Comparing his works on the coastal cliffs of Antibes, a four-month campaign he would begin in January 1888, Monet noted the differences “After Belle-Île the terrible, it will be the tender: here there is only blue, pink, and gold, but what difficulty, good God!”

Gloria Groom

Technical Report

Technical Summary

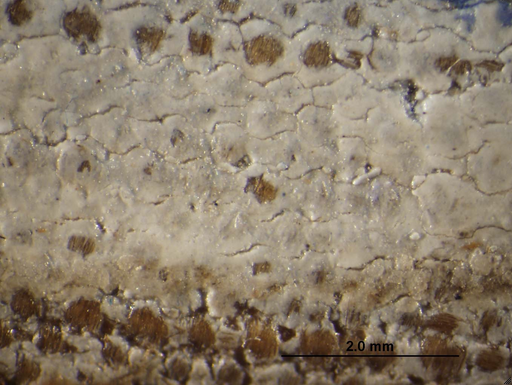

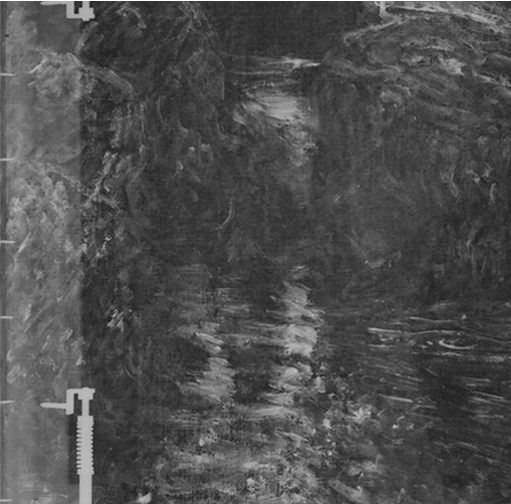

Claude Monet’s Rocks at Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île was painted on a pre-primed, no. 25 portrait (figure) standard-size linen canvas. There is a stamp from the color merchant Vieille & Troisgros on the back of the original canvas. A warp-thread match was detected with two other Monet paintings in the Art Institute’s collection: Étretat: The Beach and the Falaise d’Amont (1885; 1964.204 [W1012]) (cat. 21) and The Departure of the Boats, Étretat (1885; 1922.428 [W1025]) (cat. 22), suggesting that the fabric for these paintings came from the same bolt of material. The ground consists of a single, off-white layer. The work was directly painted with very little deviation from the initial lay-in of the composition, which appears to have been rather cursory. The placement of the rocks was delineated with light brushstrokes. Broadly applied, thin applications of dull-brown and dull-purplish-gray paint were used to lay-in the dark, shadowed areas of the rocks. In the sky there is an intermittent pale-gray underlayer. An open network of thicker, impasted strokes was applied first in the water, imparting much of the texture there. In all areas of the composition, however, the brushwork remains open, with small areas of exposed ground remaining visible at the surface. The artist worked up each major element of the composition separately, often leaving a border of exposed ground around the edges of the forms, but working back and forth between the different elements and building up the composition as a whole. The surface brushwork consists largely of wet-in-wet paint application, suggesting a fairly rapid buildup of the painting. Technical examination detected one minor modification to the composition: the extension of the reddish-brown base of the front left rock farther into the water.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 24.14).

Signature

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 86 (lower right corner, in light orange-brown paint) (fig. 24.15, fig. 24.16). Some of the underlying paint was still wet when the painting was signed, specifically the thicker, light-bluish-gray strokes near the bottom edge (fig. 24.17). This could suggest that the bluish-gray strokes were added later to the painting, as final touches, just before the artist signed the work.

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions were approximately 65 × 81 cm, which corresponds to a no. 25 portrait (figure) standard-size canvas, turned horizontally.

Weave

Plain weave; average thread count (standard deviation): 26.1H (0.8) × 28.7V (0.8) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the horizontal threads to the weft. A warp-thread match was found with Étretat: The Beach and the Falaise d’Amont (1885; 1964.204 [W1012]) (cat. 22) and The Departure of the Boats, Étretat (1885; 1922.428 [W1025]) (cat. 23).

Canvas characteristics

Moderate, fairly even cusping is present around all four edges; the cusping is slightly stronger along the left and right edges. There are a number of irregularities (i.e., thicker threads and nubs) scattered throughout the canvas.

Stretching

Current stretching: Dates to 1974 treatment (see Conservation History). Copper tacks spaced 6–8 cm apart.

Original stretching: Tack holes, spaced 5.5–8 cm apart, correspond to the cusping pattern (fig. 24.18). An additional series of small pinholes, spaced at fairly regular intervals, was observed around the edges of the painting in the area of the original foldovers (5–6 holes on each side) (fig. 24.19). It is difficult to tell when the holes were made because of subsequent abrasion around the edges; in addition, the open holes are filled with wax-resin adhesive applied during the 1974 lining (see Conservation History), while other holes have been filled and retouched. The origin and purpose of these holes is not known.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: ICA spring stretcher. Current stretcher depth: 2.7 cm.

Original stretcher: Discarded. The pre-1974-treatment stretcher may have been the original stretcher. An undated report on file records that that stretcher was five membered with a vertical crossbar and mortise and tenon joints. The report gives the following dimensions: overall, 65.5 × 81.7 cm; outside depth, 2 cm; stretcher-bar width, 7 cm; inside depth, 2.5 cm; distance from canvas position, 0.5 cm; and length of mortise, 7 cm.

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

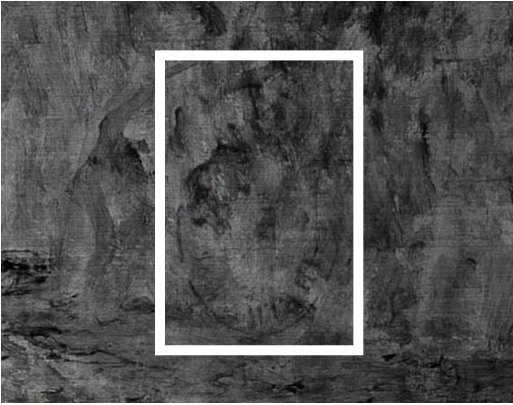

Prior to lining, a tracing was made of a supplier’s stamp on the original canvas back. Text within palette-shaped frame: H. VIEILLE E. TROISGROS / [. . .] RUE DE [. . .] / PARIS / COULEURS [. . .] / TOILES PANEAUX [sic] (fig. 24.20). The original canvas back is now obscured by the lining canvas, but traces of the stamp were visible when the painting was imaged using transmitted-infrared light (fig. 24.21).

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

The ground layer extends to the edges of all four tacking margins, indicating that the canvas was cut from a larger piece of primed fabric, which was probably commercially prepared. It consists of a single layer that ranges from approximately 10 to 100 µm in thickness (fig. 24.22). Several bubble holes were observed where the ground is exposed on the painting surface.

Color

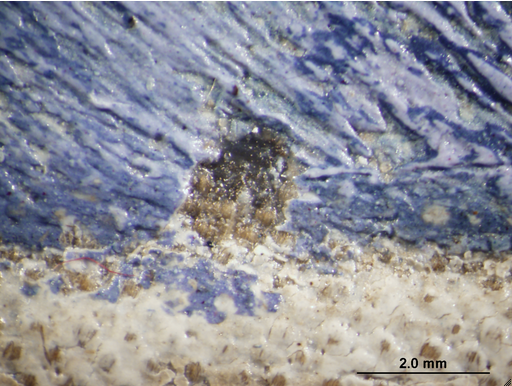

The ground is off-white. Under the microscope, a few dark and possibly red particles were visible (fig. 24.23).

Materials/composition

Analysis indicates that the ground layer contains lead white and calcium carbonate (chalk) with traces of bone black, iron oxide, alumina, silica, and silicates. Binder: oil (estimated).

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No underdrawing was observed with infrared reflectography (IRR) or microscopic examination.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

The work appears to have been executed relatively rapidly, with no significant alterations in the composition from how it was initially laid in. The brushwork is fairly open, with small areas of exposed ground visible throughout the composition, and consists largely of wet-in-wet paint applications. The work, however, was probably carried out in more than one session, since the underpainting and the thick strokes of impasto in the water appear to have been dry when the upper paint layers were built up. The main compositional features—the rocks, sky and pools of water—were built up separately with only minimal overlap along some of the edges as the painting was worked up (fig. 24.24). A border of exposed ground often remains visible at the junctures of these forms. This is particularly evident along the horizon and around the pools of water (fig. 24.25). Where the rocks overlap one another, on the other hand, there are no distinct borders between them.The artist built up the composition as a whole, working back and forth between the different areas with some wet-in-wet overlapping of strokes at the edges of some forms.

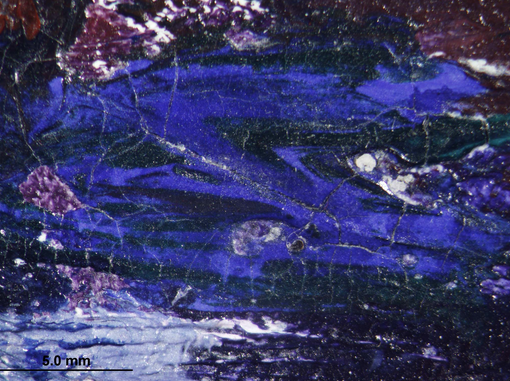

The composition was broadly mapped out to delineate the placement of the rocks; however, the lay-in appears to have been rather cursory, without the use of an overall underpainting. Along the horizon, the rocks seem to have been outlined using a relatively dry brush. This is evident, for example, along the tops of the background rocks at the far left and center, where a thinly applied stroke of dark purplish paint, deposited mainly on the high points of the canvas, seems to be related to the earliest lay-in, marking the upper edges of these landforms (fig. 24.26, fig. 24.27). The surrounding sky and water were brought up to these outlining strokes, and then the rocks were built up (fig. 24.28). In some areas, such as the plateaus at the top of the central rock, the artist used thicker, more textural brushstrokes to lay in the basic forms (fig. 24.29). The foreground rocks consist of a relatively open network of brushstrokes, with areas of exposed ground between strokes, especially on the sunlit faces (fig. 24.30). In some places, near the edges, the rocks look like they were blocked in with flat, dull-brown and purple-gray tones. The distant rocks and shadowed rock on the right side have more continuous underlayers, in the form of thin applications of dull-purple and dull-green, which are incorporated into the final painting (fig. 24.31). Only one minor adjustment was observed in the painting: the base of the left foreground rock was extended further to the right. A closer view shows that the reddish-brown paint from the rock was added on top of the water (fig. 24.32).

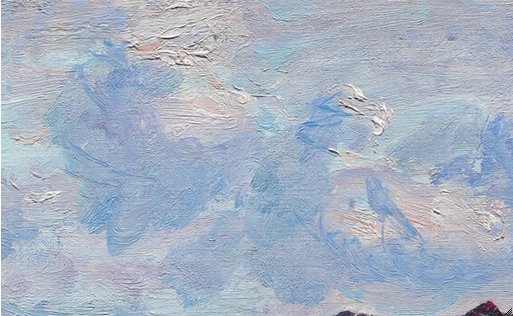

The sky appears to have been built up in a single wet-in-wet session after the initial lay-in. As observed in other areas of the painting, the lay-in—visible here and there, mainly near the horizon, as a thin, brush-marked, pale-gray layer—seems to have been very summary, with areas of ground left exposed throughout the sky, especially near the upper right corner (fig. 24.33). The brushwork consists of discrete strokes of yellow, blue, pink, and green, mixed with varying amounts of white paint, all worked wet-in-wet (fig. 24.34). There are also a few thicker brushstrokes of lead white–rich impasto, (fig. 24.35). The blue calligraphic strokes (right of center) were also applied on top of wet paint (fig. 24.36).

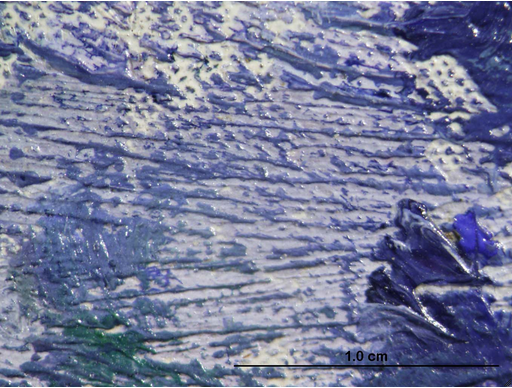

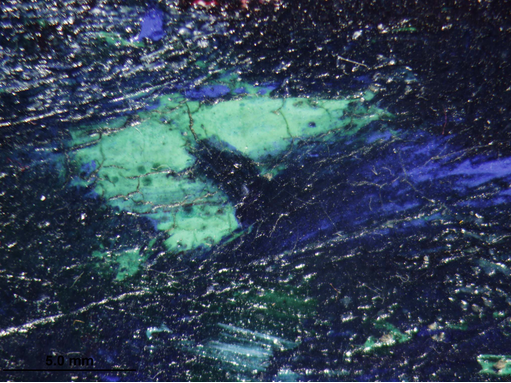

The water was laid in with a series of long, horizontal and diagonal textural strokes of pale-purplish-gray paint, which can be seen in the X-ray (fig. 24.37). The lighter areas where the sky is reflected also seem to have been indicated in this underlayer (fig. 24.38). The shorter strokes and touches of more intense blues, greens, and purples of the water were applied over top when the underlying strokes were already dry (fig. 24.39). The pale-purplish-gray underpainting strokes and the ground layer remain exposed in places, especially in the sunlit areas of the water, creating the effect of light flickering off the surface. Some of the white areas are also the result of daubs of lead white–rich strokes applied on top. Overall, the palette consists of fairly subdued or earth-toned colors, but the artist applied localized touches of relatively pure paint from the tube that is quite brilliant, especially when viewed under magnification. These are often some of the final touches to the painting and can be seen in the bright blues and greens in the water (fig. 24.40, fig. 24.41, fig. 24.42), as well as the occasional touch of bright red in the rocks. The area of water just below the horizon was applied in three or four broad horizontal strokes, with a few additional shorter strokes filling in the edges. A lightly applied, dull-greenish-blue, dry-brush stroke was applied over the dried paint of the water to emphasize the horizon (fig. 24.43).

There are a few small, localized areas of deep-blue and deep-green paint in the sky, close to the top edge, near the center and on the left side, which appear to be unintentional accretions (fig. 24.44). When viewed microscopically, these marks appear to be partially covered by paint from the sky, suggesting that they were acquired while the work was being painted. They could be accidents from handling or related to paint transfer from an easel cleat or transporting device.

Painting tools

Brushes including 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 cm width, flat ferrule (based on width and shape of brushstrokes). Several brush hairs are embedded in the paint layers.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, cadmium yellow, chrome yellow, vermilion, red lake, emerald green, viridian, cobalt blue, and ultramarine blue. UV fluorescence of areas of reddish-brown paint in the rocks and reflections suggests the liberal use of red lake.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting has a synthetic varnish, which imparts a variable surface sheen—glossy in some areas and matte in others—depending on the qualities of the paint application. During the 1974 treatment, a discolored varnish was removed; the origin of this varnish was not documented (see Conservation History)

Conservation History

In 1974, a discolored surface film was removed. The canvas was wax-resin lined and restretched on an ICA spring stretcher. A layer of polyvinyl acetate (PVA) AYAA was applied. Minimal inpainting was carried out. A layer of methacrylate resin L-46 was applied, followed by a final layer of AYAA.

Condition Summary

The painting is in good condition. The canvas is wax-resin lined and stretched flat and taut on an ICA spring stretcher. The new stretcher was slightly larger than the original; as a result a border of unpainted ground from the original tacking margin is visible around the edges of the painting. Retouching was applied to the edges to tone out the exposed ground, especially along the top edge. There is general wear and abrasion of the ground layer, as well as old paper and glue residues, on all tacking margins. The paint layer is in good condition, with only a few very small losses near the edges. Some moating and flattening of thicker impasto was observed, likely the result of the lining process. There is minimal cracking, limited mainly to thicker areas of paint application, with some localized drying cracks in areas of more fluid paint application. There are several brush hairs embedded in the paint layers. Starch-paste residues from the lining procedure are visible microscopically in the recesses of the more textural brushwork. The painting has a saturating synthetic resin varnish that is glossy in some areas and matte in others, depending on the qualities of the underlying paint.

Kimberley Muir

Frame

The current frame (installed by 1975) is not original to the painting. It is a French (Provençal), late-seventeenth–early-eighteenth-century, Louis XIV, scotia frame with carved corner foliate and center foliate-and-shell cartouches on a diamond bed with outer dentil, sanded frieze, and leaf-tip sight molding. It is water gilded over red bole on gesso with the ornament selectively burnished. The gilding is heavily rubbed; this and toning washes of umber and gray casein probably date to the pairing of the frame with the painting. The carved oak moldings are mitered and joined with angled dovetails. The original back of the frame has been planed flat, removing all construction history and provenance. A back frame has been glued to the back, and the back and interior of the frame have been overpainted. The molding, from perimeter to interior, is ovolo with carved dentil; scotia side; scotia face with corner foliate and center foliate-and-shell cartouches; fillet; sanded frieze; and ogee leaf-tip sight molding (fig. 24.45).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

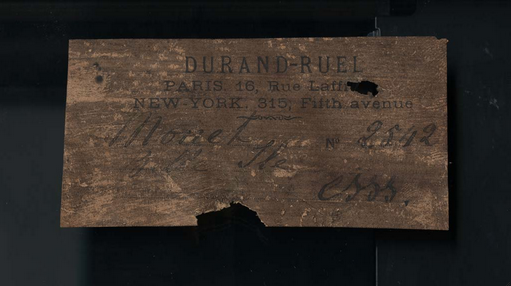

Sold by the artist to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Dec. 21, 1892, for 4,500 francs.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Dec. 19, 1895 or Jan. 4, 1896.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Mrs. John Jay (Harriet Blair) Borland, Chicago, Mar. 6, 1897, for $2,000.

By descent from Mrs. John Jay (Harriet Blair) Borland (died 1933), Chicago, to her son Chauncey Blair Borland, Chicago.

Given by Mr. and Mrs. Chauncey B. Borland, Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, beginning in 1964.

Exhibition History

Musée de Ghent, 36e exposition des beaux-arts, Sept. 1–Oct. 28, 1895, no cat. no.

Boston, Copley Society, Loan Collection of Paintings by Claude Monet and Eleven Sculptures by Auguste Rodin, Mar. 1905, cat. 75, as Belle-Isle. 1886. Lent by Mrs. John Jay Borland.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Collectors: An Exhibition Sponsored by the Men’s Council of the Art Institute, Sept. 20–Oct. 27, 1963, no cat. no. (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Masterpieces from Private Collections in Chicago, July 12–Aug. 31, 1969, no cat. no.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Monet, Mar. 15–May 11, 1975, cat. 71 (ill.). (fig. 24.46)

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 49 (ill.).

Selected References

Copley Society, Loan Collection of Paintings by Claude Monet and Eleven Sculptures by August Rodin, exh. cat. (Copley Society, 1905), p. 24, cat. 75.

Raymond Régamey, “La formation de Claude Monet,” Gazette des beaux-arts 5, 15 (Feb. 1927), p. 77 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Collectors: An Exhibition Sponsored by the Men’s Council of the Art Institute, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, [1963]), pp. 3; 17, pl. 6.

Art Institute of Chicago, Annual Report, 1963–64 (Art Institute of Chicago, [1964]), p. 19.

Art Institute of Chicago, Masterpieces from Private Collections in Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, [1969]), n. pag.

Grace Seiberling, “The Evolution of an Impressionist,” in Paintings by Monet, ed. Susan Wise, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), pp. 30, 32.

Susan Wise, ed., Paintings by Monet, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), p. 128, cat. 71 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 2, Peintures, 1882–1886 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1979), pp. 200; 201, cat. 1095.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 3, Peintures, 1887–1898 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1979), p. 269, letters 1172 and 1173.

Denise Delouche, “Monet et Belle-Ile en 1886,” Bulletin des amis du Musée de Rennes 4 (1980), pp. 48, fig. 34; 54, n. 28.

Charles F. Stuckey, ed., Monet: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin, 1985), p. 214, pl. 86.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), p. 103 (ill.).

Denise Delouche, Monet à Belle-Ile (Chasse-Marée/ArMen, 1992), pp. 51, 53, 54–55 (ill.).

Andrew Forge, Monet, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), pp. 37–39; 83, pl. 12, 107.

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue raisonné/Werkverzeichnis, vol. 3, Nos. 969–1595 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), pp. 415, cat. 1095 (ill.); 416.

Sotheby’s, New York, Impressionist and Modern Art, Part I, sale cat. (Sotheby’s, Nov. 16, 1998), p. 52, fig. 2.

Vivian Russell, Monet’s Landscapes (Frances Lincoln, 2000), pp. 66 (ill.), 160.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 81; 109, cat. 49 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 81; 109, cat. 49 (ill.).

Félicie de Maupeou, “Monet peint par ses livres,” in Claire Maingon and Félicie de Maupeou, La bibliothèque de Monet, under the direction of Ségolène Le Men, exh. cat. (Citadelles & Mazenod, 2013), pp. 46-47 (ill.).

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 2542

Paris Stock Book 1891–1901

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel New York 1515

New York Stock Book 1894–1905

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel Paris 592

Other Documents

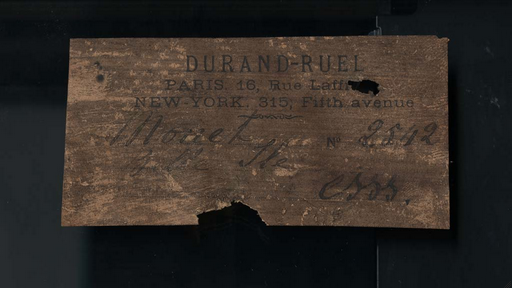

Label (fig. 24.47)

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Label

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: DURAND-RUEL / PARIS, 16, Rue Laffi[tte] / NEW-YORK, 315, Fifth avenue / Monet No2542 / Belle Ile / c[or e?]sss. (fig. 24.48)

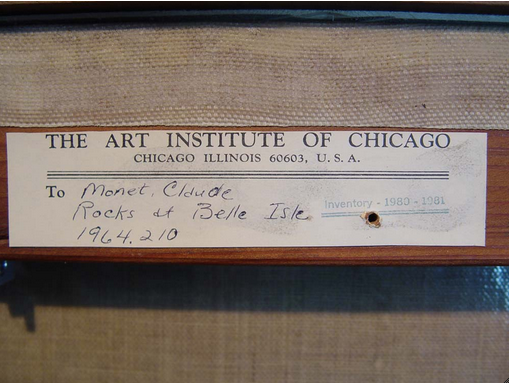

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label with handwritten text and green ink stamp

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U.S.A. / To Monet, Claude / Rocks at Belle Isle / 1964.210

Stamp: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 24.49)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / ARTIST: Claude Monet / TITLE: Rocks at Port-Goulphar, Belle-Ile (1886) / MEDIUM: Oil on canvas / CREDIT: Gift of Mr. / Mrs. Chauncey B. Borland / ACC.#: 1964.210 (fig. 24.50)

Number

Location: frame

Method: handwritten text

Content: 1964.210 (fig. 24.51)

Number

Location: lining canvas

Method: handwritten text

Content: 64.210 (fig. 24.52)

Pre-1980

Stamp

Location: original canvas; tracing in conservation file

Method: undocumented, text within palette-shaped frame

Content: H. VIEILLE E. TROISGROS / [. . .] RUE DE [. . .] / PARIS / COULEURS [. . .] / TOILES PANEAUX [sic] (fig. 24.53, fig. 24.54)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label

Content: I. C. A. SPRING STRETCHERS / OBERLIN, OHIO 44074 (fig. 24.55)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter.

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75H (B+W 486 UV/IR cut MRC filter, X-NiteCC1 filter, and Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis using a Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

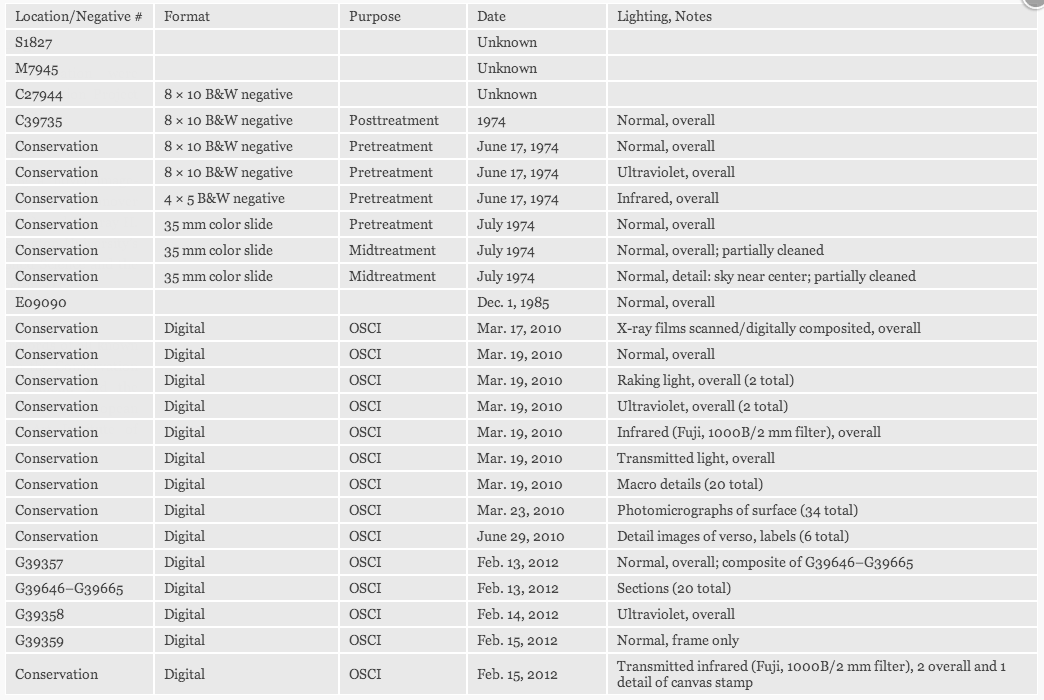

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 24.56).