Exhibition History

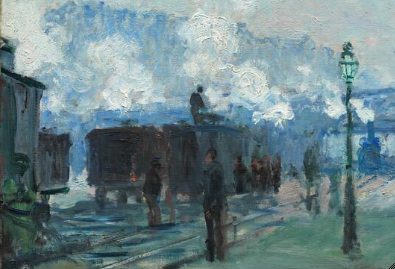

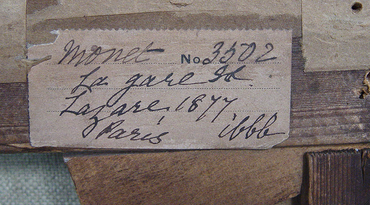

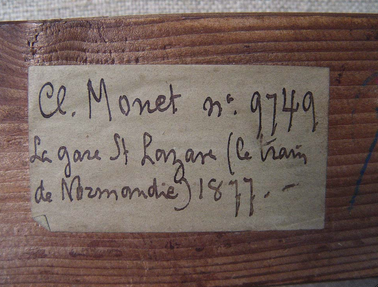

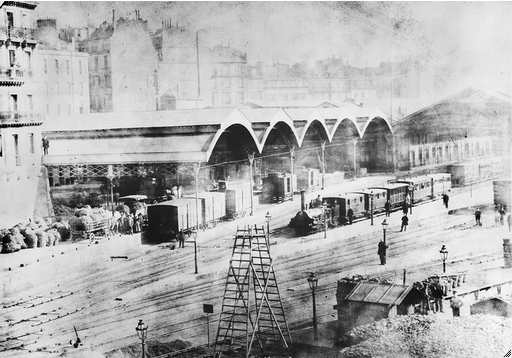

Paris, 6, rue Le Peletier, 3e exposition de peinture [third Impressionist exhibition], Apr. 1877, cat. 97, as Arrivée du train de Normandie, gare St-Lazare, appartient à M. H . . . .

Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, 6e exposition international e de peinture et de sculpture, May 8–June 8, 1887, no cat. no.

Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, Claude Monet—A. Rodin, June 21–Sept. 21, 1889, cat. 33, as Gare Saint-Lazare. 1877. Appartient à M. de Bellio.

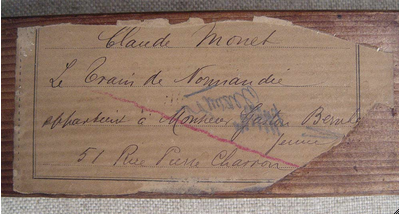

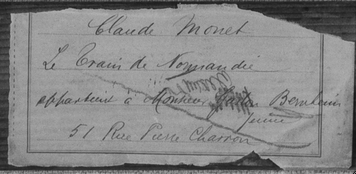

Paris, Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, Exposition Universelle de 1900, L’exposition centennale de l’art français de 1800 a 1889, May 1–Nov. 12, 1900, cat. 484, as Le Train de Normandie (à M. Alexandre Bernheim jeune [sic]).

Brussels, Libre Esthétique, Exposition des peintres impressionnistes, Feb. 25–Mar. 29, 1904, cat. 98, as La Gare Saint-Lazare. Exposition centennale, 1900. Appartient à MM. J. et G. Bernheim jeune [sic].

New York, Durand-Ruel, Monet, Dec. 2–23, 1911, cat. 8.

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, May 23–Nov. 1, 1933, cat. 299. (fig. 16.56)

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture for 1934, June 1–Oct. 31, 1934, cat. 219.

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Independent Painters of Nineteenth Century Paris, Mar. 15–Apr. 28, 1935, cat. 32.

New York World’s Fair, European & American Paintings, 1500–1900: Masterpieces of Art, May–Oct. 1940, cat. 322.

Dayton (Ohio) Art Institute, The Railroad in Painting: An Exhibition of Paintings Shown at the Dayton Art Institute, Apr. 19–May 22, 1949, cat. 50 (ill.).

Cambridge, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Charles Hayden Memorial Library, The Painter and the City, May 8–June 15, 1950, no cat. no. (ill.).

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Diamond Jubilee Exhibition: Masterpieces of Painting, Nov. 3, 1950–Feb. 11, 1951, cat. 70 (ill.).

Paris, Musée de l’Orangerie, De David à Toulouse-Lautrec: Chefs-d’oeuvres des collections américaines, Apr. 20–July 3, 1955, cat. 42 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, The Paintings of Claude Monet, Apr. 1–June 15, 1957, no cat. no.

Munich, Haus der Kunst München, Französische Malerei des 19. Jahrhunderts: Von David bis Cézanne, Oct. 7, 1964–Jan. 6, 1965, cat. 191 (ill.).

Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The Past Rediscovered: French Painting, 1800–1900, July 3–Sept. 7, 1969, cat. 60 (ill.).

New York, Wildenstein and Company, “One Hundred Years of Impressionism:” A Tribute to Durand-Ruel, Apr. 2–May 9, 1970, cat. 37 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Monet, Mar. 15–May 11, 1975, cat. 42 (ill.). (fig. 16.57)

Art Institute of Chicago, Art at the Time of the Centennial, June 19–Aug. 8, 1976, no cat.

Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Manet and Modern Paris, Dec. 5, 1982–Mar. 6, 1983, cat. 14 (ill.).

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, June 28–Sept. 16, 1984, cat. 32 (ill.); Art Institute of Chicago, Oct. 23, 1984–Jan. 6, 1985; Paris, Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais, as L’impressionnisme et le paysage français, Feb. 4–Apr. 22, 1985, cat. 70 (ill.).

Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, Jan. 17–Apr. 6, 1986, cat. 51 (ill.); Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, Apr. 19–July 6, 1986.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago’s Dream, a World’s Treasure: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1893–1993, Nov. 1, 1993–Jan. 9, 1994, not in cat.

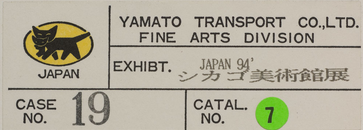

Nagaoka, Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Shikago bijutsukan ten: Kindai kaiga no 100-nen [Masterworks of modern art from the Art Institute of Chicago], Apr. 20–May 29, 1994, cat. 7 (ill.); Nagoya, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, June 10–July 24, 1994; Yokohama Museum of Art, Aug. 6–Sept. 25, 1994.

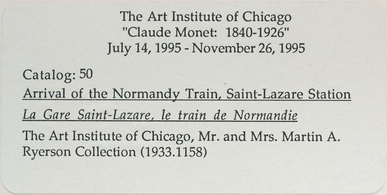

Art Institute of Chicago, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, July 22–Nov. 26, 1995, cat. 50 (ill.). (fig. 16.58)

Vienna, Österreichische Galerie, Claude Monet, Mar. 14–June 16, 1996, cat. 24 (ill.).

Copenhagen, Ordrupgaard, Impressionister i byen, Sept. 6–Dec. 1, 1996, cat. 44 (ill.).

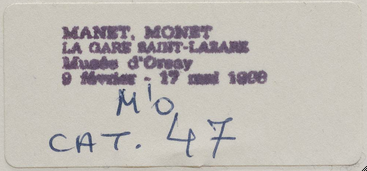

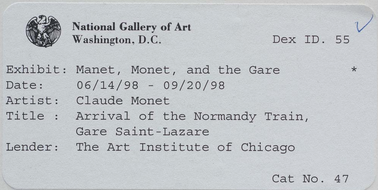

Paris, Musée d’Orsay, Manet, Monet and the Gare Saint-Lazare, Feb. 9–May 17, 1998, cat. 47 (ill.), Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, June 14–Sept. 20, 1998.

Florence, Sala Bianca di Palazzo Pitti, Claude Monet: La poesia della luce; Sette capolavori dell’Art Institute di Chicago a Palazzo Pitti, June 2–Aug. 29, 1999, no cat. no. (ill.).

Moscow, State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Klod Mone [Claude Monet], Nov. 26, 2001–Feb. 21, 2002, cat. 17 (ill.), Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, May 1–15, 2002.

New York, Wildenstein and Company, Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, Apr. 27–June 15, 2007, cat. 21 (ill.).

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 17 (ill.).

Paris, Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, Sept. 22, 2010–Jan. 24, 2011, cat. 44 (ill.).

Selected References

Catalogue de la 3e exposition de peinture, exh. cat. (E. Capiomont et V. Renault, 1877), p. 9, cat. 97.

A. P[othey], “Beaux arts,” Le petit parisien, Apr. 7, 1877, p. 2.

“Exposition des impressionnistes: 6, rue Le Peletier; 6,” La petite république française Apr. 10, 1877, p. 2. Reprinted in Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), p. 176.

Ernest Fillonneau, “Les impessionnistes,” Moniteur des arts, Apr. 20, 1877, p. 1.

Charles Bigot, “Causerie artistique. L’exposition des ‘impressionnistes,’” La revue politique et littéraire, Apr. 28, 1877, p. 1047.

Gustave Geffroy, “Salon de 1887. Hors du Salon: Claude Monet,” La justice, pt. 2, June 2, 1887, p. 1.

Galerie Georges Petit, Claude Monet—A. Rodin, exh. cat. (Imp. de l’Art, 1889), p. 31, cat. 33.

J. A., “Beaux-Arts. Exposition de la galerie Georges Petit,” Art et critique 5 (June 29, 1889), p. 76.

Gustave Geffroy, “Histoire de l’impressionnisme,” La vie artistique 3, 2 (1894), p. 68.

André Mellerio, L’exposition de 1900 et l’impressionnisme (H. Floury, 1900), p. 20.

Ludovic Baschet, ed., Catalogue officiel illustré de l’Exposition centennale de l’art français de 1800 à 1889, exh. cat. (Lemercier, 1900), p. 211, cat. 484.

Octave Maus, Exposition des peintres impressionnistes, exh. cat. (Libre Esthétique, 1904), p. 39, cat. 98.

Art Institute of Chicago, General Catalogue of Paintings Sculpture and Other Objects in the Museum (Art Institute of Chicago, 1914), p. 211, cat. 2138.

Gustave Geffroy, Claude Monet: Sa vie, son temps, son oeuvre (G. Crès, 1922) pp. 92; 118; opp. p. 136 (ill.); 272.

Camille Mauclair, Claude Monet (F. Rieder, 1924), pp. 61; pl. 20. Translated by J. Lewis May as Claude Monet (Dodd, Mead, 1924), pp. 5; pl. 20.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Guide to the Paintings in the Permanent Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1925), p. 162, cat. 2140.

M. C., “Monets in the Art Institute,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 19, 2 (Feb. 1925), p. 19 (ill.).

Florent Fels, Claude Monet, Les peintres français nouveaux 22 (Gallimard, 1925), p. 45 (ill.).

Madeleine Octave Maus, “Exposition des peintres impressionnistes,” in Trente années de lutte pour l’art, 1884–1914 (L’Oiseau Bleu, 1926), p. 323.

Louis Réau, L’art français aux États-Unis: Ouvrage illustré de vingt-quatre planches hors texte (Henri Laurens, 1926), p. 163.

Léon Werth, Claude Monet (G. Crès, 1928), pl. 26.

Xenia Lathom, Claude Monet (Philip Allan, 1931), pl. 16 (ill.).

Anthony Bertram, Claude Monet, World’s Masters (Studio/William Edwin Rudge, 1931), pl. 11.

Daniel Catton Rich, “The Paintings of Martin A. Ryerson,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 27, 1 (Jan. 1933), pp. 9, 11 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture; Lent from American Collections, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, 3rd ed., exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1933), p. 44, cat. 299.

Daniel Catton Rich, “Französische Impressionisten im Art Institute zu Chicago,” Pantheon: Monatsschrift für freunde und sammler der kunst 11, 3 (Mar. 1933), p. 77. Translated by C. C. H. Drechsel as “French Impressionists in the Art Institute of Chicago,” Pantheon/Cicerone (Mar. 1933), p. 18.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, 1934, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1934), pp. 37–38, cat. 219.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Independent Painters of Nineteenth Century Paris, exh. cat. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, [1935]), p. 24, cat. 32.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Brief Illustrated Guide to the Collections (Art Institute of Chicago, 1935), p. 28.

Hans Tietze, Meisterwerke Europäischer Malerei in Amerika (Phaidon, 1935), pp. 289 (ill.); 344–45, no. 289.

George Slocombe, “Giver of Light,” Coronet (Mar. 1938), p. 20 (ill.).

Lionello Venturi, Les archives de l’impressionnisme: Lettres de Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Sisley et autres; Mémoires de Paul Durand-Ruel; Documents, vol. 2 (Durand-Ruel, 1939), pp. 260, 303.

Thomas Craven, ed., A Treasury of Art Masterpieces, From the Renaissance to the Present Day (Simon & Schuster, 1939), pp. 506–07, pl. 123.

Walter Pach, Catalogue of European and American Paintings, 1500–1900: Masterpieces of Art, New York World’s Fair, biographies and notes compiled by Christopher Lazare, with the assistance of Anne A. Wallis, Marion Haviland, and Simonetta de Vries, exh. cat. (Art Aid, [1940]), p. 223, cat. 322.

Alfred M. Frankfurter, “383 Masterpieces of Art: The World’s Fair Exhibition of Paintings of Four Centuries Loaned from American Public and Private Collections,” Art News, May 25, 1940, pp. 41 (ill.), 64.

Regina Shoolman and Charles E. Slatkin, The Enjoyment of Art in America, with an introduction by George Harold Edgell (Lippincott, 1942), pp. 557; 609, pl. 537.

Hans Huth, “Impressionism Comes to America,” Gazette des beaux-arts 29 (1946), pp. 238, fig. 13; 239, n. 22; 240.

Oscar Reuterswärd, Monet: En Konstnärshistorik (Bonniers, 1948), opposite p. 104 (ill.); pp. 112, 281.

George Besson, Claude Monet (1840–1926), Collection les maîtres 32 (Braun, [1949]), pl. 34.

Kenneth Clark, Landscape into Art (John Murray, 1949), pl. 89; p. 102.

Dayton Art Institute, The Railroad in Painting, exh. cat. (Dayton Art Institute, 1949), cat. 50 (ill.).

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, The Painter and the City, ed. Gyorgy Kepes, with the assistance of Jane M. Bagg, exh. cat. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1950), (ill.).

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Diamond Jubilee Exhibtion: Masterpieces of Painting, exh. cat. (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1950), cat. 70 (ill.).

Lionello Venturi, Impressionisti e Simbolisti: Da Manet a Lautrec (Del Turco, 1950), pp. 59; 211, fig. 56. Translated by Francis Steegmuller as Impressionists and Symbolists (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950), pp. 61; fig. 56.

Louis Zara, ed., Masterpieces, Home Collection of Great Art 1 (Ziff-Davis, 1950), p. 118 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Masterpieces in the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1952), n.pag. (ill.).

M. K. R., “An Exhibition for Paris,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 49, 2 (Apr. 1, 1955), pp. 28, 30.

Musée de l’Orangerie, De David à Toulouse-Lautrec: Chefs-d’oeuvre des collections américaines, exh. cat. (Musée de l’Orangerie, 1955), pp. 60–61, cat. 42 and pl. 41; 129, pl. 41 and cat. 42. James Thrall Soby, “Foreword/Introduction,” in Musée de l’Orangerie, De David à Toulouse-Lautrec: Chefs-d’oeuvre des collections américaines, exh. cat. (Musée de l’Orangerie, 1955), pp. 20, 29.

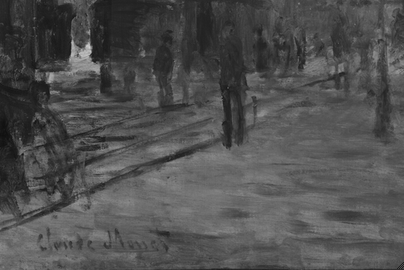

Art Institute of Chicago, “Homage to Claude Monet,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 51, 2 (Apr. 1, 1957), pp. 21–22 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Catalogue,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 51, 2 (Apr. 1, 1957), p. 33.

Denis Rouart, Claude Monet, trans. James Emmons (Skira, 1958), p. 70.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), pp. 279 (ill.), 318–19.

Leopold Reidemeister, Auf den Spuren der Maler der Ile de France: Topographische Beiträge zur Geschichte der französischen Landschaftsmalerei von Corot bis zu den Fauves (Propyläen, 1963), p. 114 (ill.).

Remus Niculeseu, “Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes,” Revue roumaine d’histoire de l’art 1, 2 (1964), pp. 215, 241, 250, 252, 253, 258, 264.

Haus der Kunst München, Französische Malerei des 19. Jahrhunderts: Von David bis Cézanne, with a preface by Germain Bazin, exh. cat. (Haus der Kunst München [1964]), pp. 416–17, cat. 191 (ill.).

Frederick A. Sweet, “Great Chicago Collectors,” Apollo 84 (Sept. 1966), pp. 201, fig. 31; 202.

Daniel Wildenstein, “Claude Monet,” in Kindlers Malerei Lexikon, vol. 4 (Kindler, [1967]), pp. 464 (ill.), 470.

Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The Past Rediscovered: French Paintings, 1800–1900, exh. cat. (Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1969), pp. 18; 146–47, cat. 60 (ill.).

Remus Niculescu, “Georges de Bellio, l’ami des Impressionnistes (I),” Paragone 247 (Sept. 1970), pp. 34, 40, 53.

Remus Niculescu, “Georges de Bellio, l’ami des Impressionnistes (II),” Paragone 249 (Nov. 1970), pp. 47, n. 2; 62; 65–66.

John Maxon, The Art Institute of Chicago (Abrams, 1970), p. 82 (ill.), 284.

Wildenstein and Company, “One Hundred Years of Impressionism”: A Tribute to Durand-Ruel, with a preface by Florence Gould, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 1970), pl. 37.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Lecturer’s Choice,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 67, 4 (Jul. –Aug. 1973), p. 11.

Donald E. Gordon, Modern Art Exhibitions, 1900–1916: Selected Catalogue Documentation, vol. 2 (Prestel, 1974), p. 90.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 1, Peintures, 1840–1881 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1974), pp. 84; 304; 305, cat. 440 (ill.); 447, pièces justificatives 60–63, 65, 68.

Grace Seiberling, “The Evolution of an Impressionist,” in Paintings by Monet, ed. Susan Wise, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), pp. 27, 28.

Susan Wise, ed., Paintings by Monet, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), p. 96, cat. 42 (ill.).

M. Therese Southgate, “About the Cover,” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 233, 3 (July 21, 1975), cover (ill.); p. 259 (ill.).

Guy Hubbard and Mary J. Rouse, Art: Discovering and Creating (Benefic, 1977), p. 178 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, 100 Masterpieces (Art Institute of Chicago, 1978), pp. 92–93, pl. 50.

Luigina Rossi Bortolatto, L’opera completa di Claude Monet: 1870–1889, Classici dell’arte 63 (Rizzoli, 1978), pp. 97, cat. 140 (ill.); 98.

Roger Terry Dunn, “The Monet-Rodin Exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit in 1889” (Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University, 1978), p. 247.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 3, Peintures, 1887–1898 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1979), p. 249, letter 986.

J. Patrice Marandel, The Art Institute of Chicago: Favorite Impressionists Paintings (Crown, 1979), pp. 56, 57 (ill.).

J. Patrice Marandel, “New Installation of Earlier Paintings,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 73, 1 (Jan.–Feb., 1979), p. 15 (ill.).

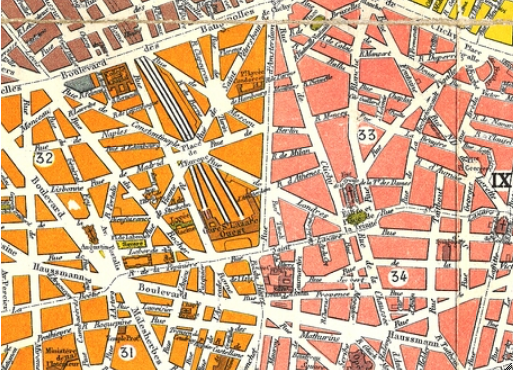

Rodolphe Walter, “Saint-Lazare l’impressionniste,” L’oeil 292 (Nov. 1979), pp. 52, 53.

Diane Kelder, The Great Book of French Impressionism (Abbeville, 1980), p. 205 (ill.).

Diane Kelder, The Great Book of French Impressionism, Tiny Folios (Abbeville, 1980), p. 121, pl. 13.

Theodore Reff, Manet and Modern Paris, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C./Eastern, 1982), pl. 7 and cat. 14.

Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, Monet (Abrams, 1983), pp. 77 (ill.), 290.

Andrea P. A. Belloli, ed., A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), p. 365.

Hélène Adhémar, “Ernest Hoschedé,” in Aspects of Monet: A Symposium on the Artist’s Life and Times, ed. John Rewald and Frances Weitzenhoffer (Abrams, 1984), pp. 69, n. 23; 70, n. 30.

Richard R. Brettell, “The Impressionist Landscape and the Image of France,” in A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, ed. Andrea P. A. Belloli, exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), p. 48.

Sylvie Gache-Patin, “The Urban Landscape,” in A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, ed. Andrea P. A. Belloli, exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), pp. 114; 116; 125, no. 32 (ill.); 126.

Charles F. Stuckey, ed., Monet: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin, 1985), p. 61 (ill.).

Richard R. Brettell, “Le paysage impressionniste et l’image de la France,” in Réunion des Musées Nationaux, L’impressionnisme et le paysage français, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1985), p. 39.

Sylvie Gache-Patin, “Le paysage urbain,” in Réunion des Musées Nationaux, L’impressionnisme et le paysage français, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1985), pp. 184; 188; 190–91; 196–97, no. 70 (ill.).

John House, “Monet and the Genesis of His Series,” in Auckland City Art Gallery, Claude Monet: Painter of Light, exh. cat. (Auckland City Art Gallery/NZI, 1985), pp. 12; 17, fig. 7.

Richard H. Love, Theodore Earl Butler: Emergence from Monet’s Shadow (Haase-Mumm, 1985), pl. 9.

Guy Cogeval, Les années post-impressionnistes (Nouvelles Éditions Françaises, 1986), p. 11, fig. 15.

Charles S. Moffett, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), pp. 205; 222–23, cat. 51 (ill.).

Richard R. Brettell, “The ‘First’ Exhibition of Impressionist Painters,” in The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, ed. Charles S. Moffett, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), pp. 189, 198.

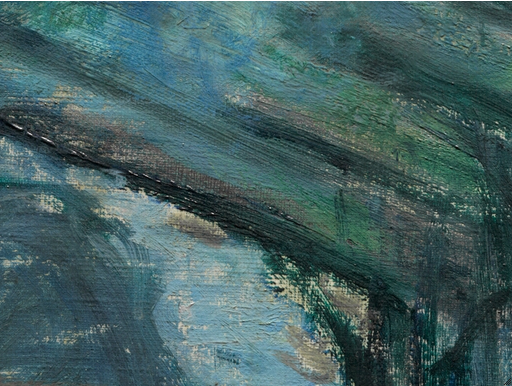

Richard R. Brettell, French Impressionists (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1987), front cover (detail); pp. 42 (ill.), 43, 118, back cover (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Master Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood and Katharine C. Lee (Art Institute of Chicago/New York Graphic Society Books/Little, Brown, 1988), pp. 9, 59 (ill.), 167.

Claire De Narbonne-Fontanieu, “Journey through a Cultural Landscape,” France Magazine 10 (Spring 1988), p. 20 (ill.).

Musée Rodin, Claude Monet—Auguste Rodin: Centenaire de l’exposition de 1889, exh. cat. (Musée Rodin, 1989), pp. 54, 79 (ill.).

Anne Distel, Les collectionneurs des impressionnistes (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1989), p. 115. Translated by Barbara Perroud-Benson as Impressionism, The First Collectors, 1874–1886 (Abrams, 1990), p. 115.

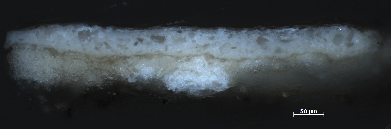

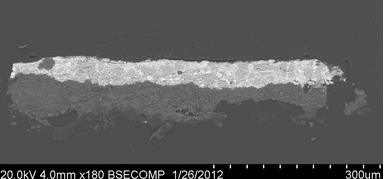

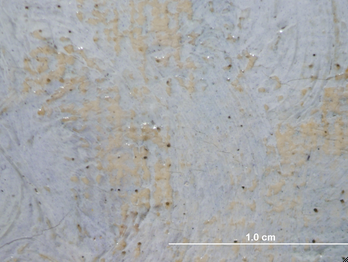

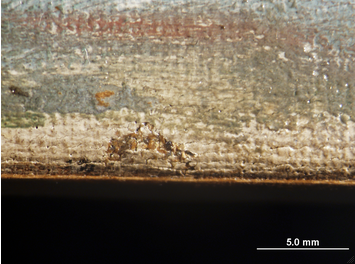

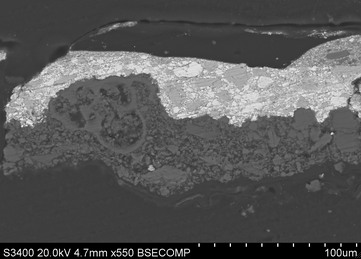

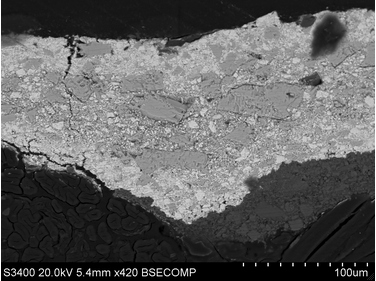

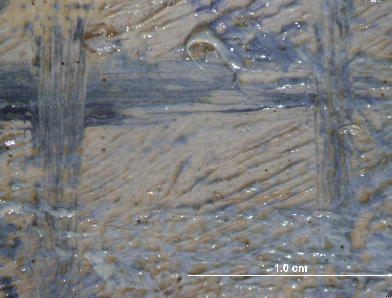

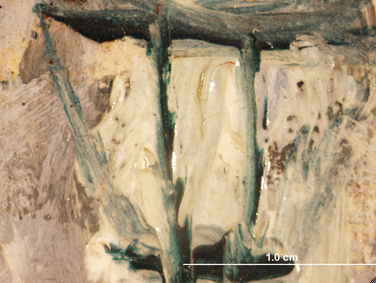

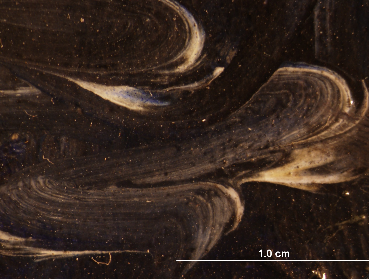

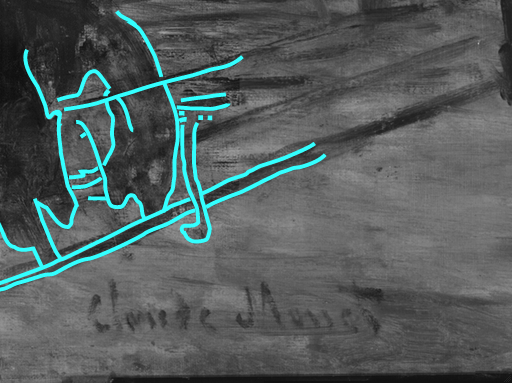

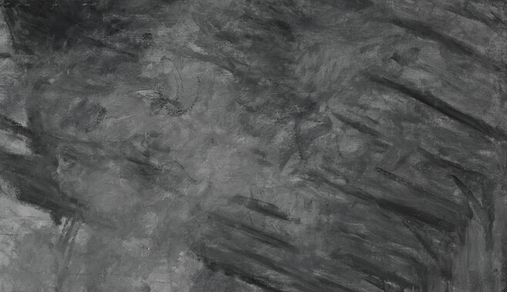

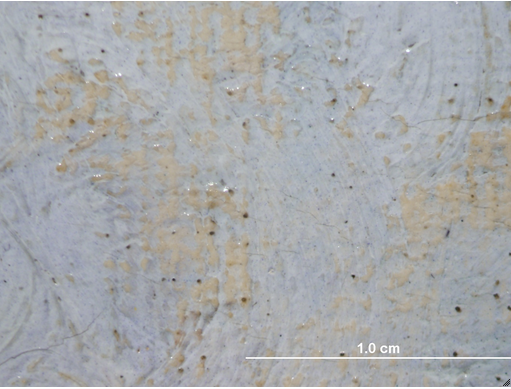

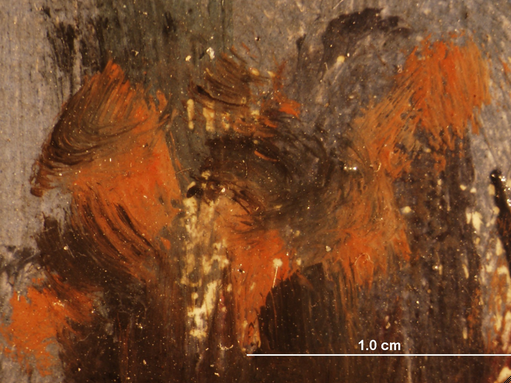

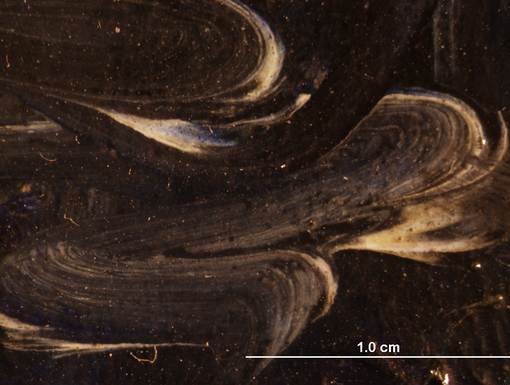

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism, exh. cat.(National Gallery, Washington, D.C./Yale University Press, 1990), pp. 166, pl. 163; 170–71.

Bernard L. Myers, Monet, Methods of the Masters (Brian Trodd, 1990), p. 67 (ill.).

Karin Sagner-Düchting, Claude Monet, 1840–1926: Ein Fest für die Augen (Benedikt Taschen, 1990), pp. 95 (ill.), 96. Translated Karen Williams Claude Monet, 1840–1926: A Feast for the Eyes (Taschen, 2004), p. 95 (ill.), 96.

Norma Broude, Impressionism: A Feminist Reading, The Gendering of Art, Science, and Nature in the Nineteenth Century (Rizzoli, 1991), pp. 74; 75; 108, pl. 30; 109, pl. 32 (detail).

Ingo F. Walther and Peter H. Feist, Malerei des Impressionismus, 1860–1920: Der Impressionismus in Frankreich, vol. 1 (Benedikt Taschen, 1992), pp. 152, 170 (ill.).

Sophie Fourny-Dargère, Monet, Profils de l’art (Chêne, 1992), pp. 82; 87, fig. 2.

Art Institute of Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago: The Essential Guide, selected by James N. Wood and Teri J. Edelstein, entries written and compiled by Sally Ruth May (Art Institute of Chicago, 1993), p. 155 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), p. 70 (ill.).

Jeffrey Coven, Baudelaire’s Voyages: The Poet and His Painters, exh. cat. (Heckscher Museum/Little, Brown, 1993), p. 90, fig. 56; 170.

Art Institute of Chicago and Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Shikago bijutsukan ten: Kindai kaiga no 100-nen [Masterworks of modern art from the Art Institute of Chicago], exh. cat. (Asahi Shinbunsha, 1994), pp. 52, cat. 7; 53 (ill.).

Charles F. Stuckey, “Chicago’s Fortune: Patrons of Modern Paintings and The Art Institute of Chicago,” in Art Institute of Chicago and Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Shikago bijutsukan ten: Kindai kaiga no 100-nen [Masterworks of modern art from the Art Institute of Chicago], exh. cat. (Asahi Shinbunsha, 1994), p. 18.

George T. M. Shackelford, “The Age of Impressionism,” in Emily Ballew Neff and George T. M. Shackelford, American Painters in the Age of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1994), pp. 19; 20, fig. 7.

Andrew Forge, Monet, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), pp. 22–24; 76, pl. 5; 106.

Charles F. Stuckey, with the assistance of Sophia Shaw, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Thames & Hudson, 1995), pp. 16, 73, cat. 50 (ill.); 202.

Lynn Federle Orr, “Monet: An Introduction,” in New Orleans Museum of Art and Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Monet: Late Paintings of Giverny from the Musée Marmottan, exh. cat. (New Orleans Museum of Art/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/Abrams, 1995), pp. 18; 19, fig. 5.

Robert Rosenblum, “Impressionismen, byen og det modern liv,” in Impressionister i byen, ed. Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark and Mikael Wivel, exh. cat. (Ordrupgaard, 1996), pp. 16, fig. 5 and cat. 44; 18. Translated as “Impressionism, the City and Modern Life,” in Impressionists in Town, ed. Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark and Mikael Wivel, exh. cat. (Ordrupgaard, 1996), pp. 16, fig. 5 (cat. 44); 18.

Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark and Mikael Wivel, eds., Impressionister i byen, exh. cat. (Ordrupgaard, 1996), p. 105, cat. 44. Translated as Impressionists in Town, exh. cat. (Ordrupgaard, 1996), p. 106, cat. 44.

Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 119, 134, 146, 173, 176.

Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, Documentation, vol. 2, Exhibited Works (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 76, 94 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet, or The Triumph of Impressionism, cat. rais., vol. 1 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), pp. 125, 128.

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue raisonné/Werkverzeichnis, vol. 2, Nos. 1–968 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), pp. 178, cat. 440 (ill.); 179–80.

Stephan Koja, Claude Monet, exh. cat. (Österreichische Galerie, Belvedere, Vienna/Prestel, 1996), pp. 67; 71, cat. 24 (ill.); 216. Translated by John Brownjohn as Claude Monet, exh. cat. (Österreichische Galerie/Prestel, 1996), pp. 67; 71, cat. 24 (ill.); 216.

Elisabeth West FitzHugh, ed., Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, vol. 3 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C./Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 286; 287, fig. 12.

M. Therese Southgate, The Art of JAMA: One Hundred Covers and Essays from the Journal of the American Medical Association (Mosby, 1997), pp. 8–9 (ill.).

Meyer Schapiro, Impressionism: Reflections and Perceptions (Braziller, 1997), p. 104, fig 41.

Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manet, Monet, and the Gare Saint-Lazare, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C./Yale University Press, 1998), frontispiece (detail); pp. 111; 112, fig. 99 (cat. 47); 188, n. 83; 199.

Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manet, Monet, la Gare Saint-Lazare, trans. Isabelle Taudière, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Yale University Press, 1998), frontispiece (detail); pp. 111; 112, fig. 99 (cat. 47); 189, n. 83.

Brigitte Béranger-Menand, “Les huit expositions impressionnistes. Profil d’un groupe: 1874–1886,” in Alain Tapié, Brigitte Béranger-Menand, and Yona Beldimaw, Chemins de l’impressionnisme:Normandie–Paris, 1860–1910, exh. cat. (Landesmuseum Joanneum, 1998), p. 26.

Emily D. Bilski, Berlin Metropolis: Jews and the New Culture, 1890–1918, exh. cat. (University of California Press/Jewish Museum, 1999), pp. 119; 120, fig. 101.

Art Institute of Chicago, Master Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 1999), pp. 8, 54, 55 (ill.).

Simonella Condemi and Andrew Forge, Claude Monet: La poesia della luce; Sette capolavori dell’Art Institute di Chicago a Palazzo Pitti, exh. cat. (Giunti Gruppo, 1999), pp. 26, 27 (ill.), 28, 29 (detail).

Thomas McBurney, Artistic Greatness: A Comparative Exploration of Michelangelo, Beethoven, and Monet (Galde Press, 1999), p. 277 (ill.)

Gina Frese, Dow Chemical Portrayed, exh. cat. (Chemical Heritage Foundation, 2000), pp. 4, 5 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), p. 54 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures from the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood, commentaries by Debra N. Mancoff (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), pp. 183, 205 (ill.).

Richard R. Brettell, Impression: Painting Quickly in France, 1860–1890, exh. cat. (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute/Yale University Press, 2000), p. 136, n. 27.

A. G. Kostenevich, Klod Mone [Claude Monet], exh. cat. (Khudozhnik i Kniga, 2001), pp. 62–65; cat. 17 (ill. and detail).

Richard R. Brettell, “Monet e Parigi,” in Monet: I luoghi della pittura, ed. Marco Goldin, exh. cat. (Linea d’Ombra, 2001), pp. 124, 125 (ill.).

Marco Goldin, L’impressionismo e l’età di Van Gogh, exh. cat. (Linea d’Ombra, 2002), p. 43 (ill.).

Richard R. Brettell, From Monet to Van Gogh: A History of Impressionism, vol. 2 (Teaching Co., 2002), pp. 6, 16, 174.

Judith Hayward, “Nature and Progress: Winslow Homer, His Critics and His Oils, 1880–1900” (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 2003), pp. 172; 362; 385, ill. 48.

Michel Laclotte, ed., The Art and Spirit of Paris, vol. 2 (Abbeville, 2003), p. 1049, fig. 6.127; 1052.

Richard Thomson, “Monet 1870–1890: Evoluzione, tradizione e decorazione,” in Turner e gli impressionisti: La grande storia del paesaggio moderno in Europa, ed. Marco Goldin, exh. cat. (Linea d’Ombra/Museo di Santa Giulia, 2006), p. 261, n. 8.

David L. Pike, Metropolis on the Styx: The Underworlds of Modern Urban Culture, 1800–2001 (Cornell University Press, 2007), pp. 221; 224, fig. 4.3.

Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), pp. 238, cat. 21 (ill.); 300–301; 303.

Joseph Baillio and Cora Michael, “Chronological and Pictorial Survey of the Life and Career of Claude Monet,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), p. 166.

Joseph Baillio and Cora Michael, “Highlights of the Exhibition,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), pp. 194; 195 (detail).

Kelly Crow, “For Charity, Gallery Plays Museum,” Wall Street Journal, May 25, 2007. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB118004588897613954.html (accessed Jan. 28, 2013).

Lance Esplund, “A Whole New Light,” New York Sun, May 17, 2007. http://www.nysun.com/arts/whole-new-light/54648/(accessed Jan. 28, 2013).

Paul Hayes Tucker, “Some Notes on Monet’s Practice,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), pp. 74, fig. 12; 75.

Richard Kendall, “Claude Monet, New York,” Burlington Magazine (July 2007), p. 511.

Roberta Smith, “Monet Arrives and Ripens,” New York Times, May 4, 2007, p. E28.

Eric M. Zafran, “Monet in America,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), p. 113.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 19 (ill.); 54 (detail); 55, cat. 17 (ill.); 57. Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 19 (ill.); 54 (detail); 55, cat. 17 (ill.); 57.

James H. Rubin, Impressionism and the Modern Landscape: Productivity, Technology, and Urbanization from Manet to Van Gogh (University of California Press, 2008), p. 116.

Ian Kennedy, “Impressionism and Post-Impressionism,” in Ian Kennedy and Julian Treuherz, The Railway: Art in the Age of Steam, exh. cat. (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art/Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool/Yale University Press, 2008), p. 159, fig. 56.

Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, “Monet’s Impressions of the Industrial Environment,” in George T. M. Shackelford, Monet and the Impressionists, exh. cat. (Art Gallery of New South Wales/Yale University Press, 2008), p. 149, fig. 33.

Art Institute of Chicago, Master Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James Cuno (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2009), pp. 9, 54, 55 (ill.).

Claudia Beltramo Ceppi, Monet: Il tempo delle ninfee, exh. cat. (Palazzo Reale/Giunti, 2009), pp. 33, fig. 18; 37.

Brian Dudley Barrett, Artist on the Edge: The Rise of Coastal Artists’ Colonies, 1880–1920, with Particular Reference to Artists’ Communities around the North Sea (Amsterdam University Press, 2010), p. 43 (ill.).

Mary Mathews Gedo, Monet and His Muse: Camille Monet in the Artist’s Life (University of Chicago Press, 2010), pp. 189; 190, fig. 13.1.

Ségolène Le Men, Monet (Citadelles & Mazenod, 2010), pp. 19; 194; 216; 217, ill. 172; 218.

Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Musée d’Orsay, 2010), p. 153, cat. 44 (ill.).

John House, “Le sujet chez Monet,” in Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Musée d’Orsay, 2010), pp. 23, 27.

Paul Stelkens, “Die Hensmann–Villa in Grosskönigsdorf,” in Egon Heeg, Axel Kurth, and Peter Schreiner, eds., Königsdorf im Rheinland, Pulheimer Beiträge zur Geschichte, Sonderveröffentlichung 34 (Verein für Geschichte, 2011), pp. 425, fig. 32; 427; 478, n. 28.